WHEN IT ALL CLICKED: Eau Claire’s School for Telegraph Operators

a century ago, students learned their dots and dashes in Eau Claire

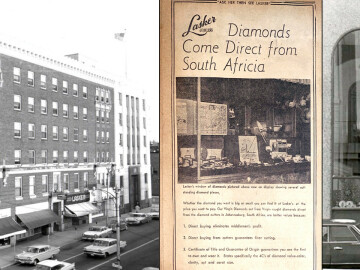

After Eau Claire became a city, several schools opened to provide an education for students after high school. Most of these schools, including Hunt’s Business College and The Conservatory of Music, were privately owned. Leonard Loken also opened a school in Eau Claire.

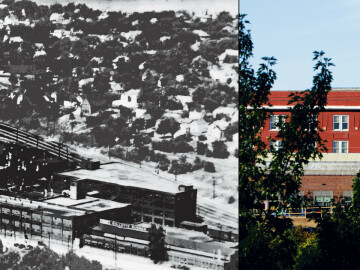

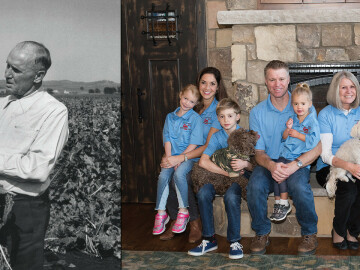

Loken was born in 1880 in Eau Claire. He learned telegraphy and then started his business, the Northwestern Telegraph School, in Eau Claire in 1906. He ran the school in several locations, including on Barstow and Wisconsin streets, for 20 years.

Three telegraph schools existed in Wisconsin: Northwestern in Eau Claire, Reidelback School of Telegraphy in La Crosse, and Valentine Telegraph School in Janesville.

A telegrapher in the previous century could be compared to a software programmer today. This industry was experiencing a rapid growth across the United States, which created a need for people with technical skills. To be accepted in a telegraphy school, a candidate needed to be very literate, be an excellent speller, be capable of learning Morse code, and have some knowledge of electricity. A couple of famous telegraphers included Thomas Edison and Andrew Carnegie.

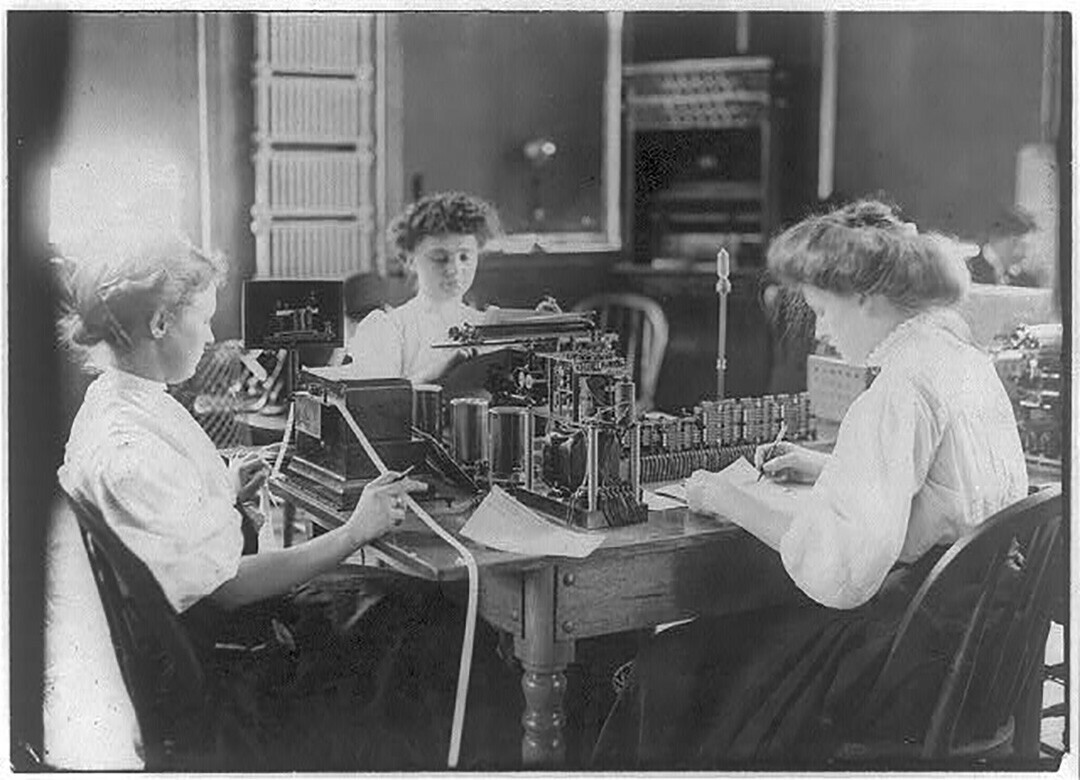

Originally only men were recruited. A 1909 ad from the Leader-Telegram discussed the “Unlimited Advantages Offered to Young Men.” However, the demand was so great that the industry began to change. The profession was a bit unique because women were well-represented in the field. They performed the same tasks as men using the same equipment and working cooperatively together. The work was promised to be “easy and pleasant, the pay good, and the opportunities for advancement unlimited.”

The school sponsored a men’s baseball team and a women’s softball team, The Clicks. In addition to their athletic teams, the school also participated in dances. In 1914, 100 people gathered in Laycock Hall for a dance. Leonard announced beforehand that there was to be absolutely no tango dancing. Waltzes, two-steps, and quadrilles were allowed. The music was furnished by Sherman’s Orchestra. The dancing continued until very late and no one left until the last dance.

In June of 1927, Gov. Fred Zimmerman appointed Loken as register of deeds upon the death of Anton Anderson, and the school was closed. For two decades it trained a special work force that used technology to make the Chippewa Valley a thriving community.