The Speed Started Here

Menomonie native Harry Miller’s innovative engines dominated the Indy 500 for decades

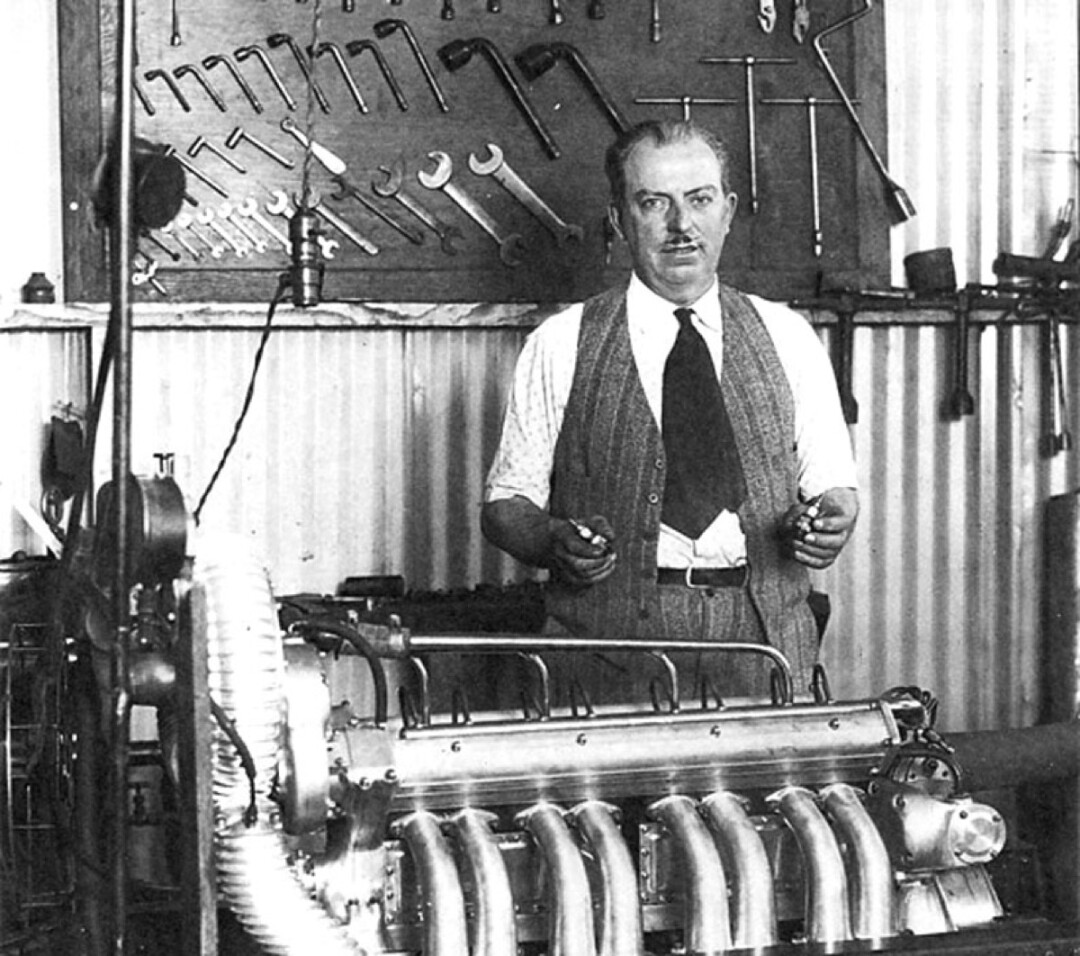

One of the greatest innovators in the history of auto racing was born right here in the Chippewa Valley. Unless you’re a devoted student of the history of early racing, you probably haven’t heard of Harry Miller. That’s a shame, because his life is a story with more twists and turns than a road rally, complete with enormous success and (literally) deadly failure.

“Harry Miller was, quite simply, the greatest creative figure in the history of the American racing car.” – racing historian Griffith Borgeson

Miller was born in 1875 in Menomonie to Jacob and Martha Miller. While his father was a schoolteacher, musician, and painter, young Harry was more interested in mechanical matters. According to a biographical sketch of Miller published by the Dunn County Historical Society, he quit school at age 15 and took a job at the Knapp, Stout & Co. machine shop. A couple of years later, the young Miller left town for Salt Lake City, the first of many, many moves in his life. The next year, he bounced back to Menomonie, then moved to Los Angeles in 1895, where he worked in a bicycle shop and married Edna Inez Lewis.

Soon enough – like a racer zooming around after another lap – Miller and his bride returned to his hometown. He worked as a foreman at Globe Iron Works and in his free time fiddled with motorcycles and even motor-driven boats. In fact, he created a four-cylinder outboard motor but didn’t pursue the idea, while a co-worker named Ole Evinrude went on to become famous for his namesake outboard motor. As one biographer wrote, “In this early part of his career, Miller exhibited what would become a characteristic inability to concentrate on any one project (at) a time.”

During the first decade of the 20th century, Miller moved repeatedly (California, Ohio, Michigan), patented a spark plug, and created a carburetor with extra jets that made it ideal for fast vehicles. The carburetor “dominated the market” between 1911 and 1921, allowing Miller to get more deeply involved in the auto industry – especially auto racing, writes biographer Timothy Gerber.

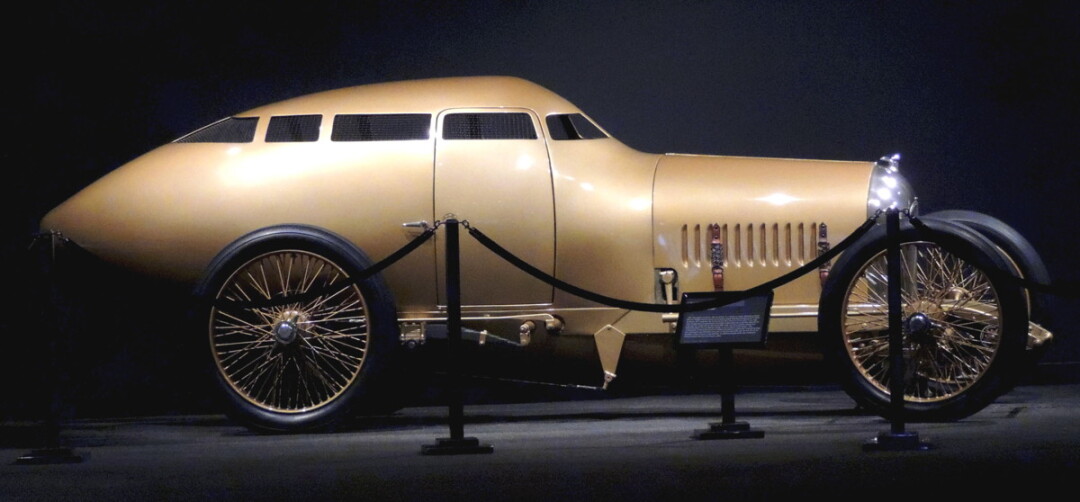

Ever the innovator, in 1915 Miller began rebuilding engines with aluminum pistons instead of steel, making them lighter and more powerful. Famed driver Bob Burman rode one of Miller’s engines to several road-race victories before dying in a crash caused by a blown tire. Miller then turned to aircraft engines – creating a good six-cylinder model – but his collaborator died in a plane crash. It almost goes without saying that the early days of motorized transport were relatively risky. With an eye toward increasing safety, Miller worked with racer Barney Oldfield to create an innovative car that was billed as “crash proof”: It had a roll cage and an enclosed, teardrop shape, which led it to be nicknamed the “Golden Submarine.” (While it was fast, it wasn’t seaworthy: One driver almost drowned when he crashed the car in a flooded infield.)

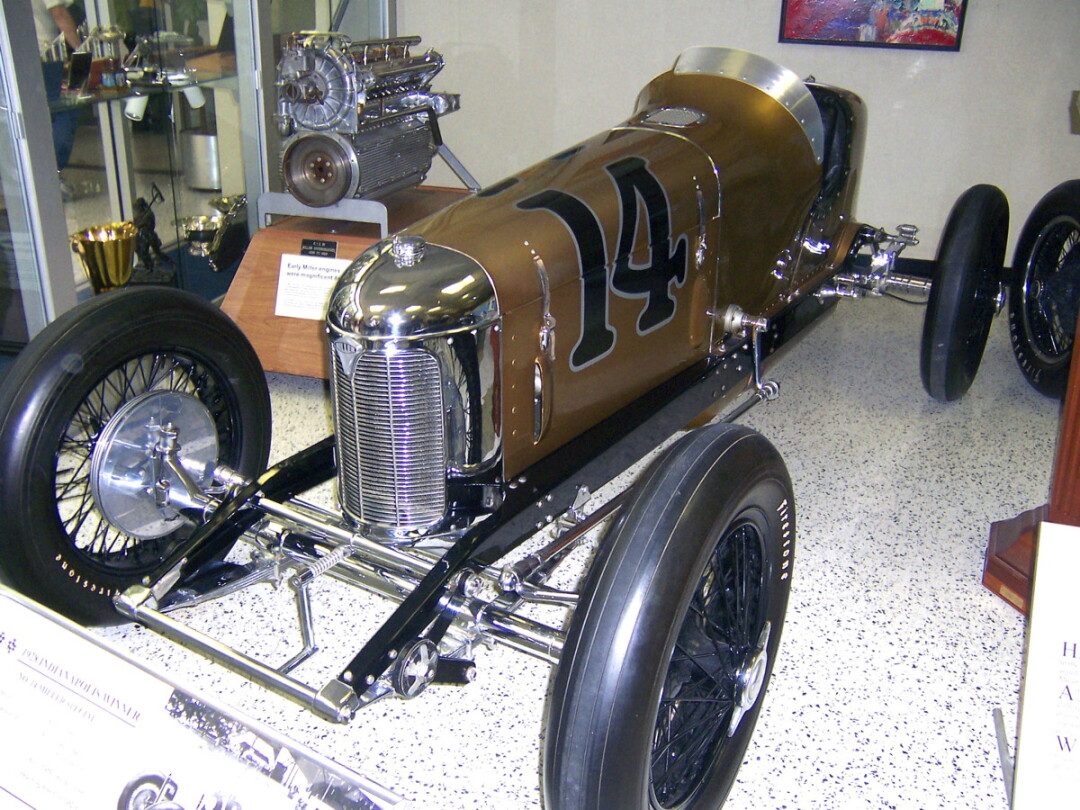

Miller’s next great innovation came in 1922, when the eight-cylinder Miller 183 – built to conform to a rule that limited engines in the Indianapolis 500 to 183 cubic inches (3 liters) – was driven to victory in 10 races, including the Indy 500. That began a decade-and-a-half era in which when Miller-designed engines dominated Indy racing: Between 1922 and 1938, Miller engines drove to victory at the Brickyard an amazing 12 times. It’s worth noting that Miller and his engineers built these winning engines in an era of frequently-changing specifications. In 1923, engines were limited to 122 cubic inches; the limit dropped to 91.5 cubic inches in 1929, and ballooned to 366 cubic inches in 1930. Big or small, Miller’s engines remained the gold standard.

His cars were elegant as well as swift. As Preston Learner wrote in a 2013 Automobile magazine article about a convention of Miller cars in Milwaukee, the vehicle that won at Indy in 1926 “(is) not a car at all. It’s a razor blade suspended on four tall, skinny wheels. At its broadest point, the body is a mere eighteen inches wide.” And yet, even with its puny 91.5-cubic inch engine, the car’s been clocked at 171 mph.

Miller was a trendsetter in other ways, pioneering front-wheel drive and four-wheel drive vehicles. The latter, however, proved to be his ruin: “Unfortunately, Miller’s four-wheel-drive race car could not have come at a worse time than during the Great Depression,” writes biographer Gerber. “No one had the money to buy such a sophisticated piece of machinery.” Miller filed for bankruptcy in 1933, and his engineering team fell apart. His former employee, Fred Offenhauser, bought Miller out, and developed Miller’s engine into the powerful Offenhauser – or “Offy” – engine, which dominated Indy racing until the 1970s. The engineering acumen that had begun with a mechanically minded boy in Menomonie held sway for half a century in that most famous of auto races.

While Miller died of a heart attack in 1943 at age 67, his name lives on in racing history books and his cars can be found in automotive museums. As racing historian Griffith Borgeson wrote, “Harry Miller was, quite simply, the greatest creative figure in the history of the American racing car.”