Letters, Lost and Found

salvaging pieces of history from an estate sale

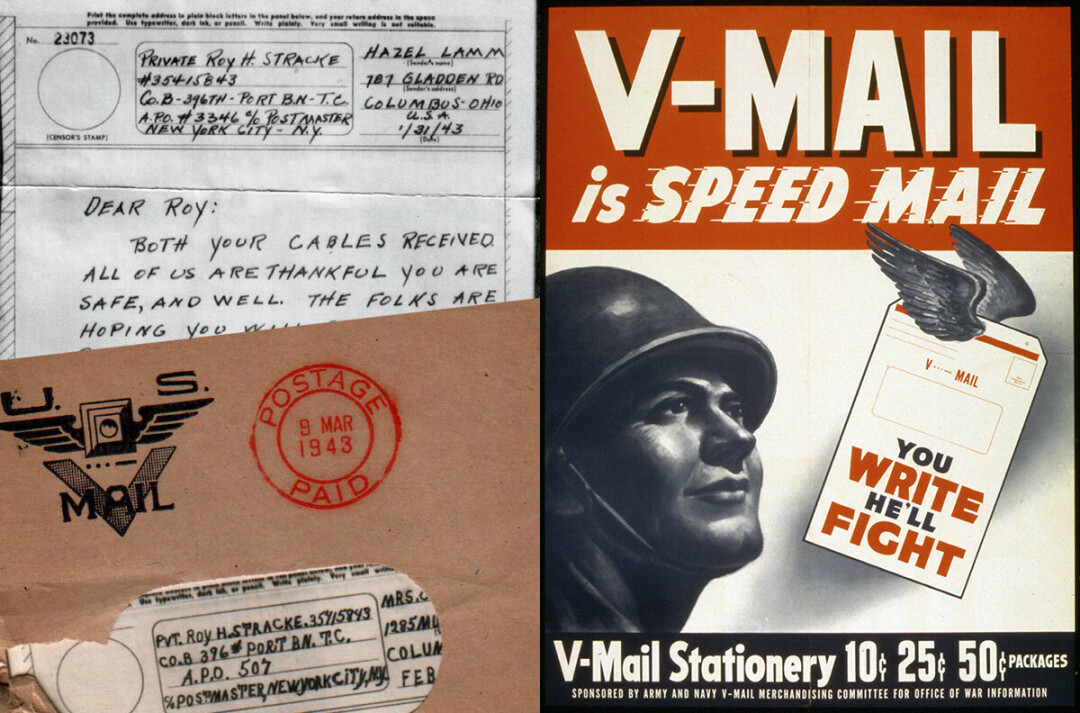

V FOR VICTORY. During World War II, more than 1 billion letters were sent to and from U.S. servicemembers via V-Mail, a system by which letters were copied to film to reduce their size, then reprinted when they arrived at their destination. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

The letters lay on a hassock upstairs in the house where there was an estate sale. Curious, I picked them up and, as soon as I looked at the dates on the letters, I determined I would ask about them. No price tag accompanied them. Old chandeliers and furniture, paintings and figurines didn’t entice me, but these letters did. I paid $2 for the set of 10 and left with my treasure: letters dated from 1942 to 1945. One of the letters was only about 4 by 5 inches with the term “V-mail” at the top.

Doing a little research, I found that the “V” stood for “victory” and that, early in 1942, the military used these pieces of paper for service people to write letters home. The hyphen in the phrase V-mail was printed as three dots and a dash, signifying victory. A small box on the top held the receiver’s address. The letter from a serviceman was cleared by a censor and photographed onto 16 mm black-and-white camera film. From here, the reel was shipped or flown to a processing center near the general location of the addressee, reduced to a piece of 4 by 5 inch black-and-white photographic paper, and dropped into a mailbag for delivery. This process saved room for more important shipments. During the Second World War, more than 1 billion V-mail letters were processed, according to the U.S. Postal Service. The Victory letter shares the news that The Red Cross gave a Christmas box to us with candy and cigarettes and a few other things in it. A sentence begins Some of the fellows got a couple – and here the words are crossed through, probably by a censor, and unreadable. And I imagine a melancholy man who hopes he’ll be back by next Christmas.

Another letter dated February 1944, tells of a man getting his induction papers and having to have a physical in June. This letter from one woman to another says, So if he passes he will have to go to war too. The tone seemed matter-of-factly. As I read the letter, I thought of the millions of women who were left behind, not knowing whether their son or husband or lover would return. I wondered if this man returned to his family.

Once an elderly couple were present as their possessions were being sold. I had to leave as I couldn’t bear to see them watching as their belongings sold, one by one. I knew their rocker had once rocked a baby of theirs; I was certain this mother and grandmother had served many meals on the dishware being offered.

Some letters are from a young woman in nursing school in Chicago. She writes during her long shift at night, anticipating final tests and future practicum in a children’s hospital where the children are all under 14 years of age. She, too, asks about a man who’s coming home on furlough.

Thankfully, there are no “Dear John” letters.

Many of the letters begin the same way, How are you? Ok, I hope. English and business teachers would cringe. But the letters always show the hunger for news – for information. Have you heard from Juanita? How is Carol? Have you been down home any lately? How does Marvin behave now that you have him tied up and fenced in? How did you spend the holidays? And always a plea for someone to write back. They don’t care that all the letters begin the same way.

Discovering these letters made me think about estate sales in general. Going to estate sales is a strange endeavor. I feel like I’m going into a home uninvited and sometimes wonder what the owner would think. Usually the owner has died or is now residing in a nursing home or with a son or daughter. I often leave with some small piece since my home has long been furnished with larger pieces. And strangely, I remember the home, if not the person, where each piece came from. There’s the Roseville vase from a tiny house on the East Hill of Chippewa Falls, the Italian lamp from a doctor’s home on the West Hill, and a set of Robert Browning poetry from a neighboring town. No wonder my decorating is called eclectic. Often it’s a piece of needlework – either a framed sampler or a needlepoint pillow or embroidered pillowcases. I can’t stand the thought of leaving something for the dumpster that someone worked on for months or years. There’s a framed Christmas poinsettia needlepoint that someone dared to price at only $3. I simply had to rescue that because the sale was nearly over, and I just knew it would get thrown away. Once an elderly couple were present as their possessions were being sold. I had to leave as I couldn’t bear to see them watching as their belongings sold, one by one. I knew their rocker had once rocked a baby of theirs; I was certain this mother and grandmother had served many meals on the dishware being offered. Better not to know what’s happening to your possessions that you once prized, dusted, and sat in. I’m reminded of that each time my husband tells me my estate sale will last three days with the church ladies serving lunch on the lawn.

These letters I now possess are written on old tablet paper that once cost 5 cents for a whole pad, or it’s the tiny, notelike piece that was photographed and printed. I’ll keep them in a file. Perhaps in years to come, someone will find them and wonder why someone kept a tiny piece the size of a present-day note. Perhaps the person will read them, research the V-mail piece, and decide they’re worth saving. I hope so.

Connie Russell lives with her husband, Tim, on Lake Wissota where she reads, writes, and works with the Friends of the Library.