The Deep Roots of Legendary Local Trees

a pair of mighty giants that live on in Chippewa Valley memory

Without exaggeration, it can be said that Eau Claire and the Chippewa Valley wouldn’t be what they are today if it weren’t for the immense forests that covered northern Wisconsin until the 19th century.

When European settlers began to arrive in large numbers, there were millions of acres of white pines and millions more covered in hardwoods. The Chippewa and Eau Claire rivers were ready-made natural highways to carry this lumber, and the first sawmill was built in what would become Eau Claire in 1846.

The logging industry reached its peak in the 1890s, and Eau Claire boomed. At one time, there were approximately 16 sawmills in Eau Claire, nine of them on Half Moon Lake alone. The naturally occurring oxbow lake served as an immense log holding pond, as did the manmade Dells Pond just upriver. The two were connected by log flume – a watery chute that carried logs right through the city, sometimes aboveground and sometimes below the street.

The felling of most of the forest ultimately led to both ecological and economic transformation, and Eau Claire’s last sawmill closed a century ago. Yet trees remain vital to the region. Here are the stories of two of the most notable.

Council Oak

While the lumber industry was built on white pines, one of the most historically important local trees wasn’t a pine, but rather an oak. According to oral tradition, a massive oak tree on UW-Eau Claire’s campus, near where Little Niagara Creek empties into the Chippewa River, was once a meeting site for Native American tribes, notably the Ojibwe and Dakota. (An 1825 treaty between the tribes and the U.S. government put the boundary between Ojibwe and Dakota territory approximately at the creek.)

By the 1960s, the Council Oak was a source of pride for the campus, serving as a meeting place for students, a gathering place for Native Americans celebrating their culture, and a symbol for the university itself. However, it was seriously damaged in a storm in 1966 and was ultimately toppled by a windstorm in 1987. At the time, it was estimated to be 300 years old.

Despite its physical death, the Council Oak lives on in several ways. Some of its wood was preserved and crafted into objects, including a bench that can be found in McIntyre Library. Meanwhile, the image of the oak is still part of UW-Eau Claire’s official seal. And in 1990, a sapling was planted on the site of the original tree. This new Council Oak stands near the Davies Student Center, the construction of which was altered to accommodate the tree.

So what is the true history of the original Council Oak? We may never know for certain. In an interview recorded as part of a UWEC oral history project, Rick St. Germaine – a professor emeritus of history and former chairman of the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Tribe – said he was once skeptical that the Council Oak would have been large enough to serve as a meeting place 200 years ago. However, he said, over time he became more open to the idea that the surrounding landscape would have been full of notable landmarks for Ojibwe and Dakota warriors. “Knowing the Indian mind they would look for things like Little Niagara,” he said.

Two-Leader Pine

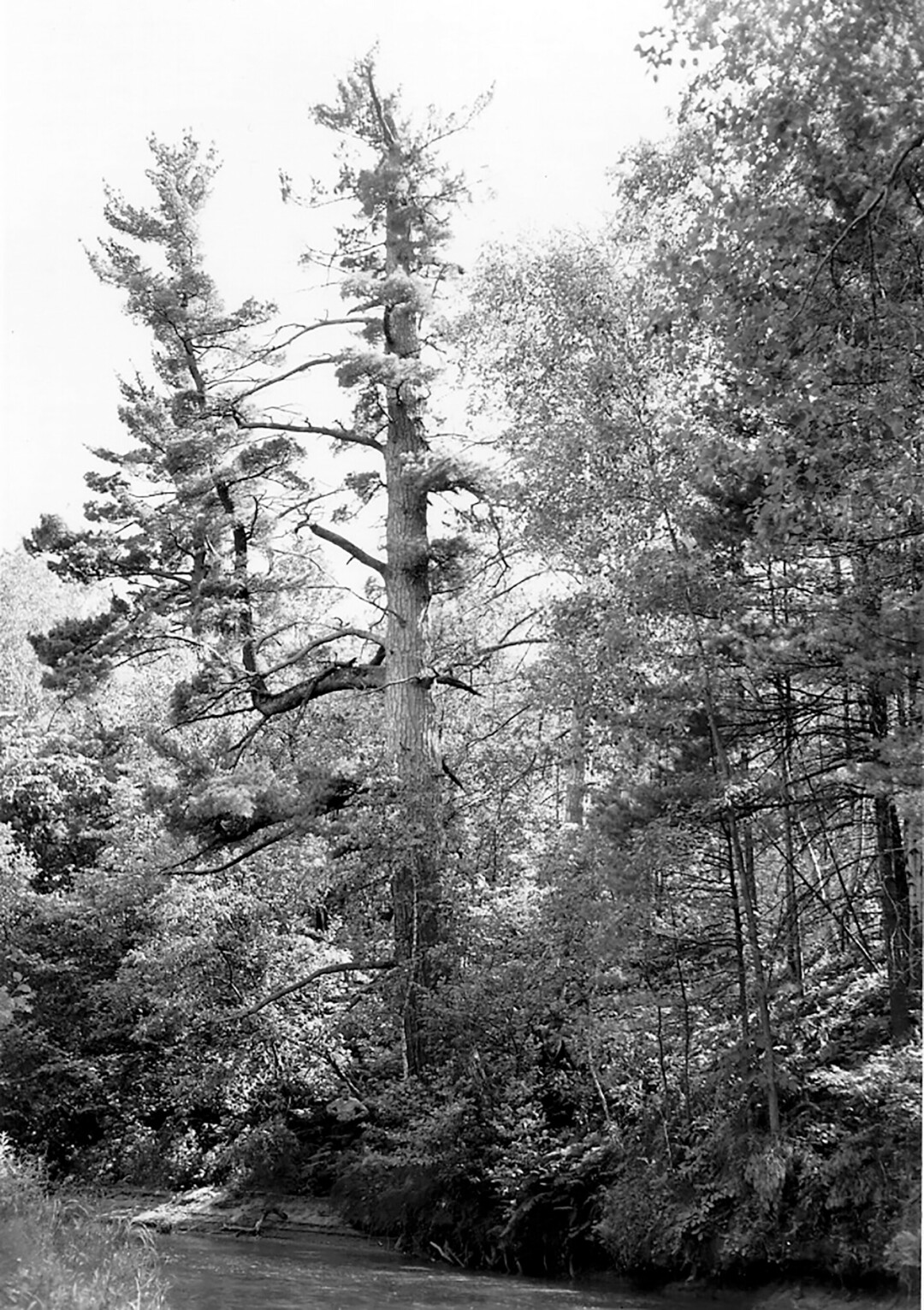

Another famed Eau Claire-area tree – this one a white pine – was likewise ancient and somewhat mysterious. Bruce Allison’s 2005 book, Every Root an Anchor: Wisconsin’s Famous and Historic Trees, recounts memorable trees from across the state. Among them is the so-called Two-Leader Pine, which grew in a relatively inaccessible site on the bank of Lowes Creek about two miles south of Eau Claire. The tree was a rare example of a virgin white pine, having avoided the ax presumably because it was in a difficult – if not impossible – to reach spot. It was later dubbed the Two-Leader Pine because of its twin tops: At some point long before, the central stem of the tree – its leader – had been broken, and the tree sent up a new “terminal shoot” from a lateral branch. “A strange-looking tree indeed,” Allison wrote.

We would likely know nothing of the tree were it not for the eloquence of late outdoorsman and writer Jim Fisher. In a Leader-Telegram column published in 1976, Fisher recalls discovering the Two-Leader Pine as a boy 50 years earlier. The tree, he imagined, had witness the passage of since-vanished species such as caribou and bison as well as the arrival of white settlers and the rise and fall of the logging industry.

“It was immense, two of us could not reach around it,” he wrote. “From a distance it just looked like a big tree. One had to get close to realize just how big it was.”

In 1950, Fisher wrote, he measured its circumference at nearly 14 feet, and he submitted a photo of the tree to the Wisconsin Conservation Bulletin. By 1976, the tree was dying, with just a wisp of green at the top.

“Next year,” he wrote, “I will visit the tree one last time. I will take my lunch as I did when I was young and I will sit with my back against the rough bark of that massive trunk and I will pay my respects to a friend.”