The Coffee King: the UWEC grad behind Seattle’s Best

Jim Stewart didn’t always love coffee. In fact, as a UW-Eau Claire student in the 1960s, he generally avoided the stuff. “It was just nauseating,” he recalls now. “I didn’t like it.”

He does remember one cup he enjoyed, however, a mug of java he drank in his kitchen at the Sigma Tau Gamma fraternity house before embarking on an early-morning fishing trip. There was something about the moment – the setting, maybe, or perhaps the roast of the beans or the particular way the grounds were brewed that day – that stuck in his mind, making a memory that’s still vivid decades later.

Little did Stewart know, but he eventually would be instrumental in facilitating countless coffee-tinged memories by founding what became one of the most recognizable and seminal coffee-shop chains in the nation, Seattle’s Best. From humble beginnings as the proprietor of a seasonal Washington State ice cream shop, Stewart became a pioneer in the coffee business, helping lead the Pacific Northwest trend that took the beverage from a ho-hum morning drink to one of America’s favorite little luxuries.

BEGINNING AS A BLUGOLD

More than 45 years after his first foray into selling coffee, today Stewart is revered for his knowledge of the business – particular his acumen trading directly with coffee farmers, something he pioneered in the 1970s during a sojourn to coffee-growing nations from Indonesia to Costa Rica (where he eventually met his wife, the proprietor of a coffee estate).

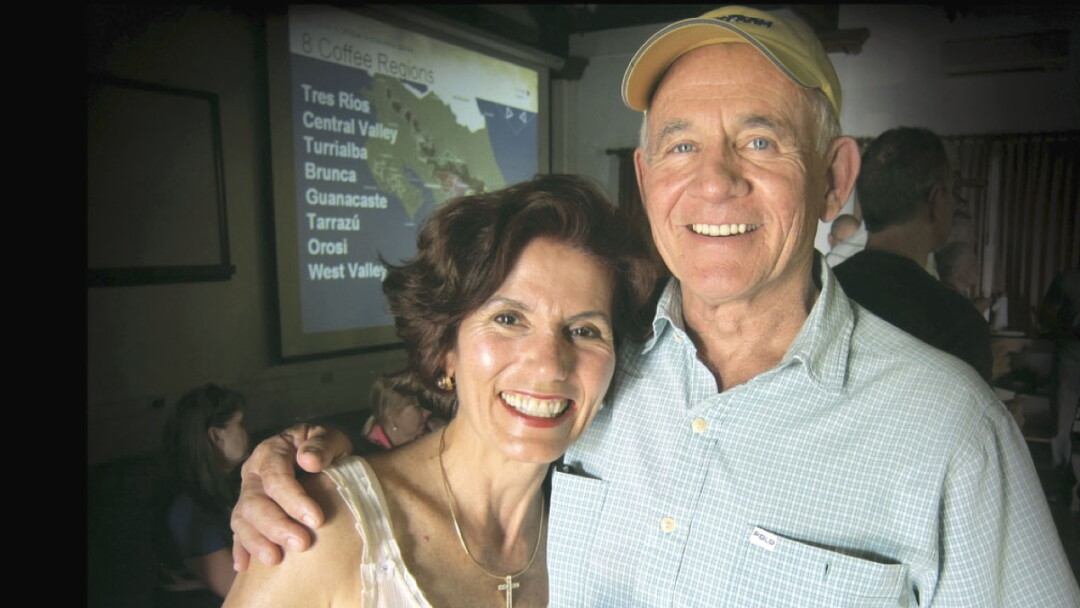

In early October, Stewart and his wife, Luz Marina Trujillo, were guests at UW-Eau Claire’s inaugural Entrepreneur Week, where the couple spoke to students, faculty, and alumni about their years in the business.

Stewart grew up in Osceola and attended UW-Eau Claire, where he studied biology and chemistry. “I spent hours in the library here, not because I was doing so much, but because I was such a slow reader,” he recalls.

While he didn’t study business, he was certainly entrepreneurial, charging $1 a head to cut hair in the dormitory bathroom for beer money. “You could drink for the whole weekend for $12 in those days,” he recalled.

In the late 1960s, Stewart’s parents moved to the state of Washington, and he soon followed, leaving UW-Eau Claire just a half credit shy of graduating. (He was finally granted a degree in 2002; he says the university determined his life experience in the business world was worth at least half a credit.) In the summer of 1969, he and his brother, Dave, opened The Wet Whisker, a seasonal ice cream shop in a former barbershop on Whidbey Island, Wash. The following year, they added coffee to the menu – and the rest is java history.

“All we knew about the business was we liked ice cream, and we learned to like coffee,” Stewart says. The business wasn’t an overnight success: Stewart recalls living frugally, eating a lot of ice cream, and spending one summer living in a tent behind the shop. The brothers persevered despite tight times. “Coming from Wisconsin, we know how to work hard,” he recalled, describing their attitude. “If that’s not enough, we can work harder.”

On his way to optometry school in California in 1970, Stewart stopped at The Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf in Los Angeles, an early gourmet coffee shop. It was there that he was first exposed to high-quality coffee and began to understand that coffee from different parts of the world had different characteristics. He worked at the shop for a few months, and took his newfound knowledge of coffee and how to roast it back to Washington. In 1971, the Wet Whiskey began roasting coffee. That same year, the very first Starbucks opened in nearby Seattle. A West Coast trend was brewing.

IT STARTED IN SEATTLE

Over the next two decades, specialty roasted coffee, espresso drinks, and the overall culture of coffee shops became popular in the Pacific Northwest and eventually nationwide. Why did the trend start in Seattle? In part, it’s the region’s rainy, overcast “coffee-drinking weather,” Stewart says. In addition, Stewart notes, the region is populated by people who’ve relocated from other parts of the country, and such people are drawn to coffee shops as a way to meet their new neighbors.

Stewart began roasting coffee on Vashon Island, near Seattle; his style of roasting was similar to that found in northern Europe, where lighter roasts were favored. This is in contrast to the darker, southern European-style roasts popularized by Starbucks. “You had two different companies in Seattle with two different approaches,” he says. “People would go to parties and have heated discussions about their favorite kinds of coffees.”

The Stewarts’ business expanded to include several locations in the Seattle area – including a spot on the waterfront and in a posh mall – and eventually was renamed Stewart Brothers Coffee. In the late 1970s, Stewart pioneered buying coffee direct from growers rather than brokers. The move both saved money and allowed Stewart to control the quality of the coffee he was receiving. He still prefers the direct-trade route, even as fair trade certification has become ubiquitous in the coffee industry. Stewart argues that direct trade allows more profits to stay in the hands of farmers by cutting out middlemen such as wholesalers and certification agencies, which coffee retailers must pay for the privilege of putting the fair trade label on their products.

By the late 1980s, even as it continued to grow, Stewart Brothers Coffee ran into a problem: A similarly named (but older) company in Chicago challenged their right to use the Stewart Brothers name. Coincidentally, at about that time the company’s coffee was declared the best coffee in Seattle in a 1989 contest, and it took the opportunity to rename itself Seattle’s Best Coffee.

By the 1990s, business was booming, having grown in a few short years from $10 million to $80 million or $90 million annually. Stewart sold a controlling share of the company to a group of investors, but kept his hand in the business as the chief coffee buyer. He retained this role through another sale of the company – this time to AFC Enterprises, which also owned Popeyes Chicken and Cinnabon – but lost it in 2003 when Seattle’s Best was bought out by its biggest rival, Starbucks.

In the years since, Starbucks has continued to expand the Seattle’s Best brand. As of 2014, the company says, Seattle’s Best coffee was “available in more than 50,000 locations including cafes, college campuses, restaurants, hotels, airlines, cruise ships, grocery stores and movie theatres.” This includes 10 locations in the Eau Claire area alone, including Subway and Burger King restaurants.

CUP HALF FULL

While the Starbucks buyout separated Stewart from the company he founded, it didn’t cut him out of the coffee business. Today, Stewart helps several Seattle-area coffee roasters buy direct from farmers and tends to his own small organic coffee farm – Finca El Gato – on a Costa Rican mountainside. He uses the proceeds from the coffee he grows there to fund a charity, the Vashon Island Coffee Foundation, which helps with development projects, such as building schools, in the Central American villages where coffee pickers live.

It was in Central America that Stewart met his wife of 17 years, Luz Marina Trujillo. a third-generation coffee grower. Originally from Columbia, in 1989 she moved to Costa Rica to take over the family business in the country’s famed Tarrazú coffee-growing region. It was there that she met Stewart in the 1990s.

Luz worked hard to change the focus of the business from quantity to quality. Her beans are processed, fermented, and dried on site. The farm emphasizes sustainable agriculture, growing coffee in the shade, which not only preserves trees but also protects the berries from the sun and rain and helps control weeds. (As herbicides aren’t used on the farm, machetes also come in handy.)

Back in the 1990s, the plantation’s first direct-to-roaster client was Seattle’s Best Coffee. “His enthusiasm inspired us to work even harder – so much so that I married him,” Luz says of Stewart.

While Stewart has unparalleled expertise about coffee, his advice to coffee drinkers is practical. Allow a six-ounce cup of coffee to warm your hand, enjoy the brew, and never let someone refill a half-consumed cup, he advises. “The personality of your cup of coffee changes so much with the temperature,” he says. “The real characteristics don’t come out until the second half of the cup.”

Perhaps, after a long career in the coffee business, the same could be said about life.