authors by John Hildebrand, illustrated by Daniel Reich |

Many, many years ago I met an actress at a New Year’s Eve party in New York. A month later I called to breathlessly say that I loved her. Or maybe that I had fallen in love with her. In either case, a long pause followed.

“Yes, but what does that mean?”

Turns out it didn’t mean much of anything. There’s a difference between love and romance, and the actress had already figured out that we’d had the latter. The party had been both its beginning and apogee; the phone call was its denouement.

Romance is the perfect subject for movies because they each require only a limited attention span. Love, on the other hand, is like a Russian novel, lengthy and dense and ultimately unfilmable. Where love is knowing too much about someone (and ignoring parts you don’t like), romance is not knowing but being excited to find out. Think of the scene in Casablanca when Rick asks the mysterious Ilsa Lund: “Who are you really and what were you before?” And Ilsa replies, “We said no questions.” Exactly.

”

Romance is the perfect subject for movies because they each require only a limited attention span. Love, on the other hand, is like a Russian novel, lengthy and dense and ultimately unfilmable.

JOHN HILDEBRAND

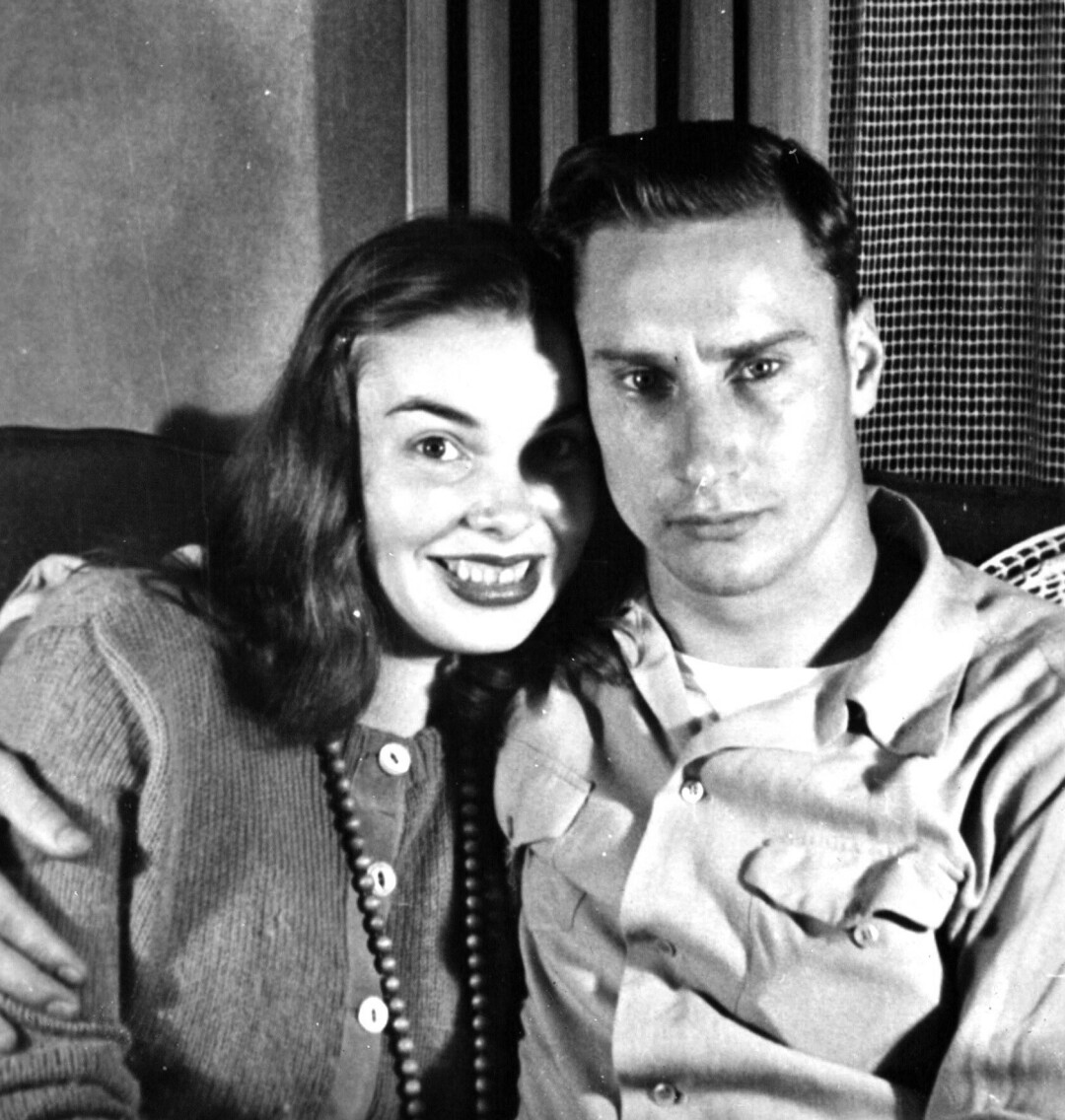

I’ve been thinking about love and romance ever since a nephew sent me some black-and-white photographs of my parents taken in Los Angeles in 1943 – the same year, it turns out, that Casablanca was released. Southern California may not seem as exotic as French North Africa (or the backlot at Warner Brothers), but it was new to my parents, and it shows. I’d never seen that look on my parents’ faces when they were alive but recognized it now – people in the flush of romance.

I only learned the backstory of the photographs near the end of my mother’s life. Against her own father’s wishes, she’d eloped, boarding a train in Chicago by herself and crossing the country to marry my father before he shipped overseas. The only wedding photograph shows the two of them on the steps outside a church in Pasadena. No bridesmaids or groomsmen – just my mother in a new dress and my father in uniform. They’re on their own in the world for the first time and everything is fresh and new – their first apartment, their first time away from family, even their own bodies. They seem a little giddy – as if only playing at adulthood, which had arrived all too suddenly. It’s the war, of course, and knowing, as Rick tells Ilsa, ”that the problems of (two) little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” So they snap pictures of each other – at the beach, behind a row of liquor bottles, in their rented bungalow – as if they can’t believe their luck, or how long it will last, or what the future holds.

What the future holds is me and my brothers. In the final photograph, taken a decade later on Christmas morning, my parents are back in the Midwest, sharing a front stoop with three little boys in matching cowboy outfits and the grandfather who’d tried to put the kibosh on marrying a soldier. The exhilaration that once lit my parents’ faces has been replaced by something that could be mistaken for exhaustion but is really love. After 40 years of marriage, I recognize that look as well.