Tom Giffey, illustrated by Daniel Reich |

You can find a lot of things on Google Street View. I found my father.

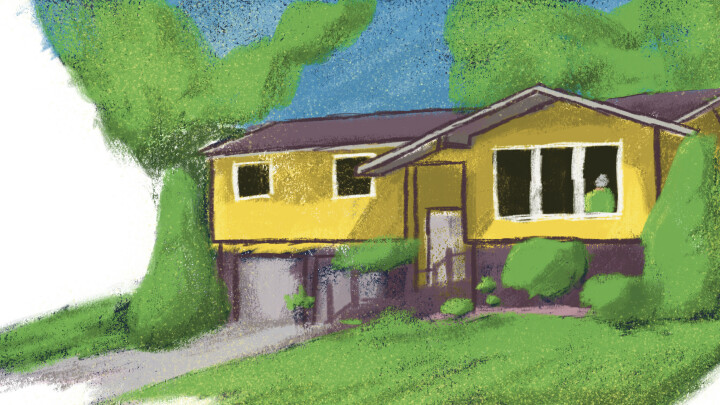

I wasn't looking for him, but there he was, sitting in his favorite chair, his back to the picture window in the living room of the house I grew up in. He may have been watching TV, but judging by the slight downward tilt of his snow-white head, he was probably reading – maybe the newspaper, maybe the Atlantic or The New Yorker, maybe a weighty historical volume. The notation in the lower corner of the screen (which read “Image capture: Aug. 2013”), the sunshine, the open windows, and his T-shirt indicate it was a warm day.

To Google and anyone using Street View – the virtual online mapping service – the location was 614 W. Fountain St. in Dodgeville, Wisconsin. To me, the address was a bit more metaphysical, in a place deep inside somewhere near my heart. The image that filled my computer monitor one evening a few years back was both entirely unexpected and utterly familiar.

Except for a few trees, the house looks much the same as it did throughout my childhood: Same yellow paint with white trim, the same potted geraniums carefully cultivated by my mother, same trio of large picture windows. All these I had expected to see. What I hadn’t expected to see was my dad, who died several years earlier. But there was Neil Giffey, preserved in digital amber courtesy of a series of image files gathered by a specialized car that had cruised past. The Google car hadn’t captured a ghost exactly, but in some ways, at that moment, I felt that it had. My breath caught in my throat, and I felt an odd mix of excitement at the discovery and melancholy at the reminder of my dad’s absence. Here he was, recorded two years before his death, enjoying a favorite activity in a favorite spot – a spot I still frequently visit, a spot that looks virtually unchanged, save for one detail: his absence. An emptiness in his favorite chair and in his family’s hearts, a gap all the digitized data in the world couldn’t fill.

”

Except for a few trees, the house looks much the same as it did throughout my childhood: Same yellow paint with white trim, the same potted geraniums carefully cultivated by my mother, same trio of large picture windows. All these I had expected to see. What I hadn’t expected to see was my dad, who died several years earlier.

TOM GIFFEY

I'm sure there are plenty of such stories hidden in plain sight in Street View. Google has used cars – and boats, snowmobiles, tricycles, and even backpack-mounted cameras – to gather images along more than 10 million miles of roads in 83 countries and all seven continents. With Street View, you can cruise around New York, Nairobi, Moscow, Baghdad – even a few spots in Antarctica – not to mention nearly every small town in Wisconsin.

For privacy’s sake, identifying details like license plates and faces are automatically blurred in Street View. Apparently, the algorithm is smart enough to distinguish the front of a head from the back of one, which is why my dad’s hair is easily recognizable. It was a feature both distinguishing – and distinguished. I’m sure Dad would appreciate that both his privacy and his dignity have been preserved.

That head of hair is recorded in both my memory and Google’s. In the 21st century, we’ve outsourced a lot of our memories, downloading the kind of data that past generations had to keep in their heads onto our digital devices. And yet many memories of my father are contained in my mind alone. Others are tied to physical objects; his warm winter socks, for example, which I sometimes wear. His musty Army uniform, which I do not. Many are recorded in documents, photographs, and audio recordings – hours of them – in which he told the story of his life for posterity. These recordings are still emotionally difficult for me to listen to, but I feel blessed to have them. More than photographs of our faces (or the backs of our heads), more than physical possessions, it is our personal stories that truly capture who we are.

One particularly strong memory of my dad – the image of him sitting in his favorite chair – has been outsourced to a multinational corporation, an unfeeling behemoth that could delete the information with a wave of its digital wand. For this reason, I have saved a screengrab – a blurry digital image that is as precious to me as the 19th-century tintypes of my ancestors were to my dad. Nonetheless, it’s still comforting to be able to surf Google Maps, to click on the little yellow stick figure and drop him on the right block, and to look at my dad again. Or, at least at the back of his head. The sign at the corner of the block may read Fountain Street, but for me, it’s Memory Lane.