In both the skiing community and among those in Cable, Popp and the ABSF’s vision seems to have a faith placed in it that previous attempts to remake Telemark have not earned.

Gary Crandall summarizes the Cable community’s feelings: “We all have a strong desire for Telemark to regain a viable operation bringing back that huge national and international focus.

I see that the Birkie is taking a more measured approach and hopefully this time the glory that was Telemark will once again blossom.”

“We all have a strong desire for Telemark to regain a viable operation bringing back that huge national and international focus.”

Gary Crandall

former race director, Chequamegon Fat Tire Festival

Meanwhile, for those for whom life’s tapestry weighs heavily towards skiing and for which Telemark was a touchstone, there is already much to laud.

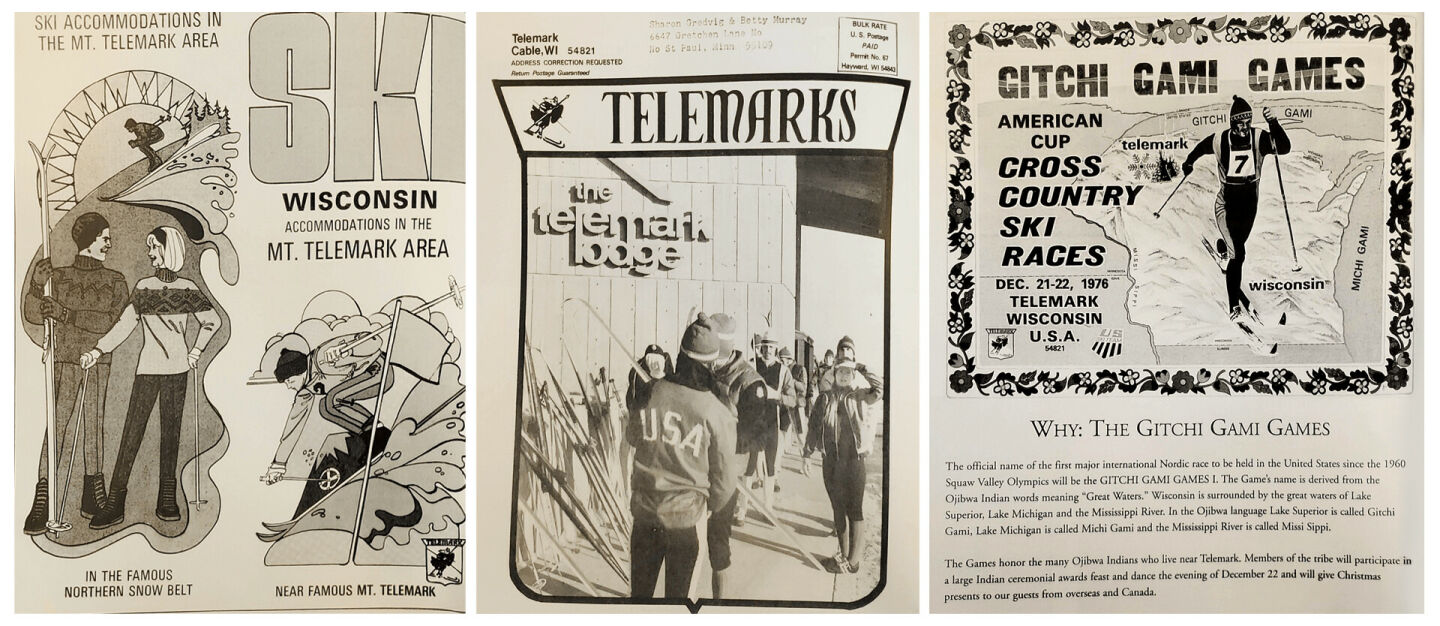

Eau Claire skier David Ecker said of his time growing up at Telemark during its waning years that it “was one of the few places in the world that (cross-country) skiing was the center of the universe.”

“Many of us have spent the last handful of years mourning the loss of Telemark,” Ecker said.

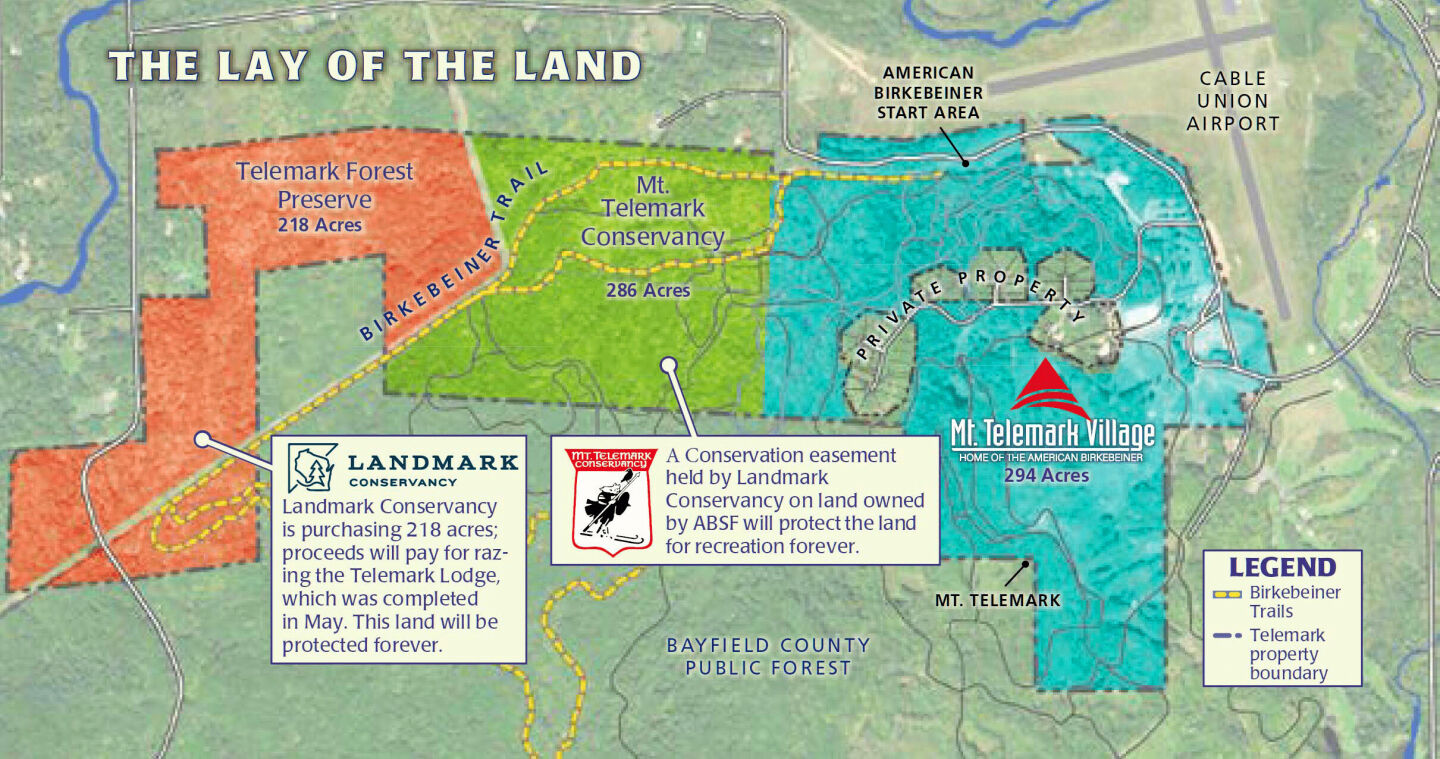

“I am especially excited by (the Birkie’s) sustainable plan to focus on land conservancy, rather than over-commercializing the property.”

For Popp, meanwhile, the nuts, bolts, facts, and figures of steering the ABSF all point towards the spectral joy, spirit,

and connection to the world that the name Telemark carries in the Northwoods:

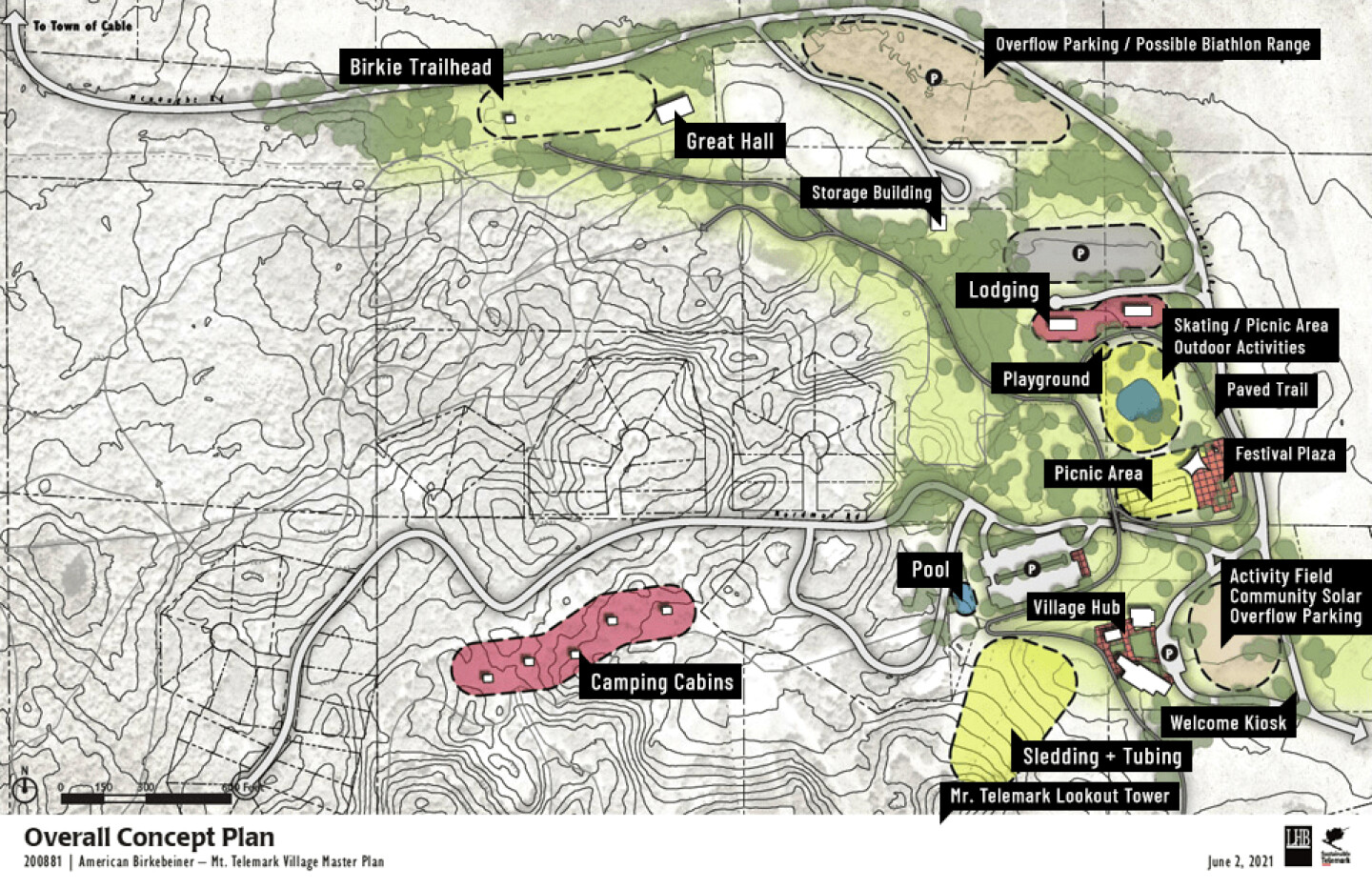

“I think about hosting a World Cup here (in 2024), how amazing would it be to line up Jessie Diggins next to Johannes Høsflot Klæbo” – a seven-time Olympic medalist Norwegian skier –

“next to your dad, my mom, a kid from Minneapolis who didn’t know what skiing was two years ago, a kid from the Lac Courte Oreilles reservation, and on and on.

When we all get to sit at the same table, we all get to inspire each other, and that’s my ultimate dream at the end of the day.”

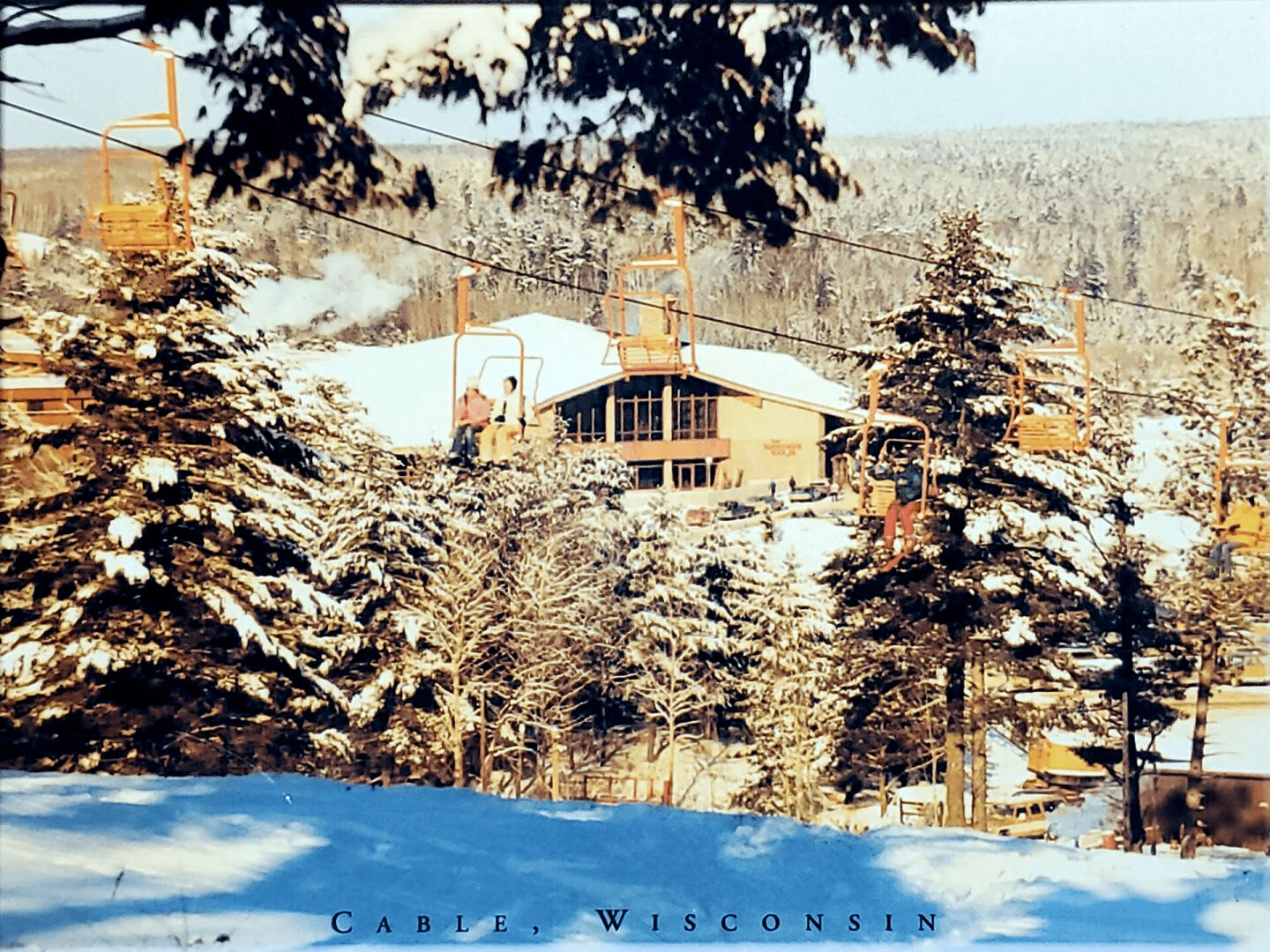

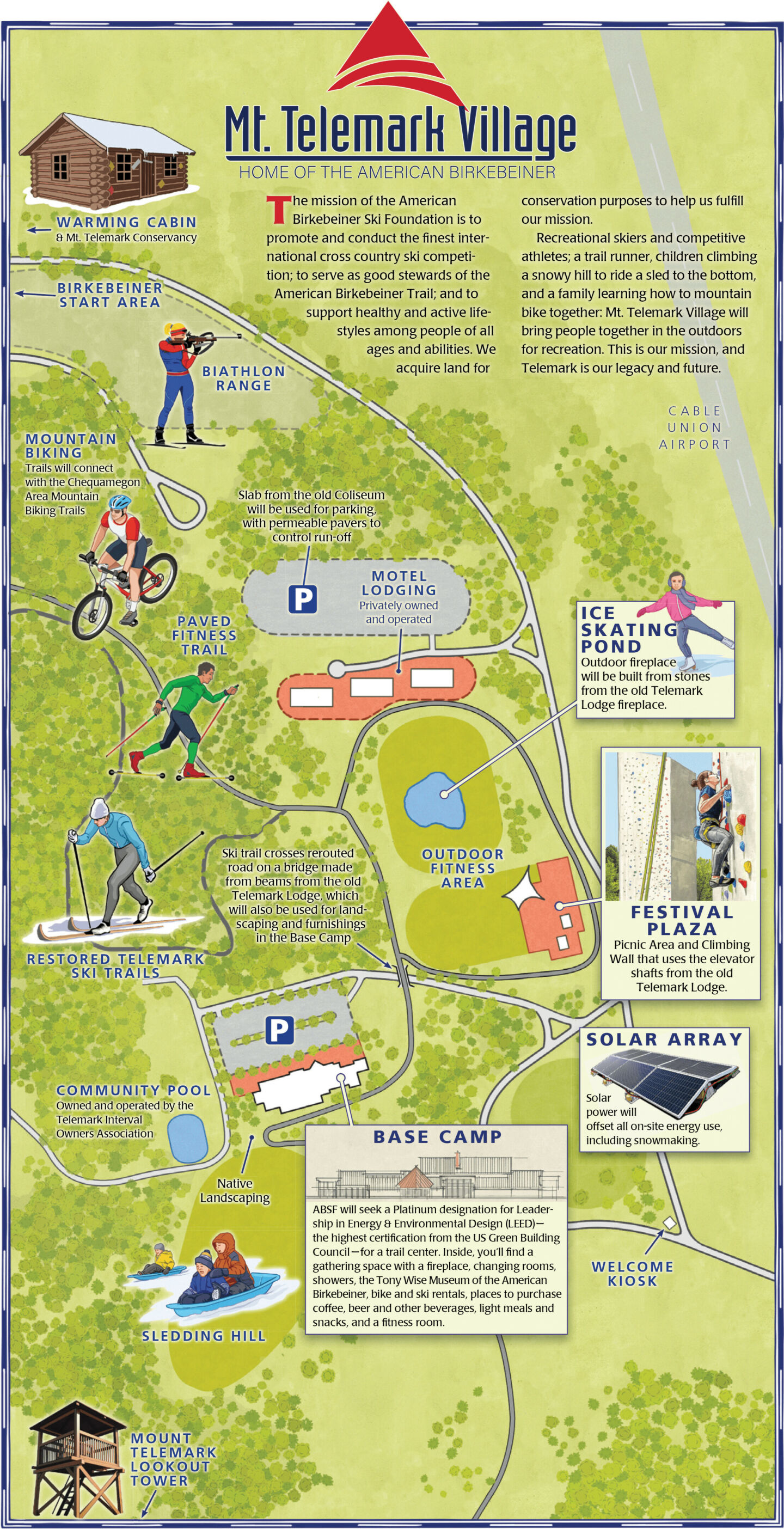

To see that dream, you can now head two miles East of Cable, up a chip-sealed road where the bridges offer glimpses of the vernal pools and springs coming off the Namekagon,

take in the glacial knoll that’s stood for 10,000 years, brought life and connection to northern Wisconsin, and belongs to all once again.

It is a place not unlike others strewn throughout the Northwoods – this is after all, one of the most beautiful places on Earth –

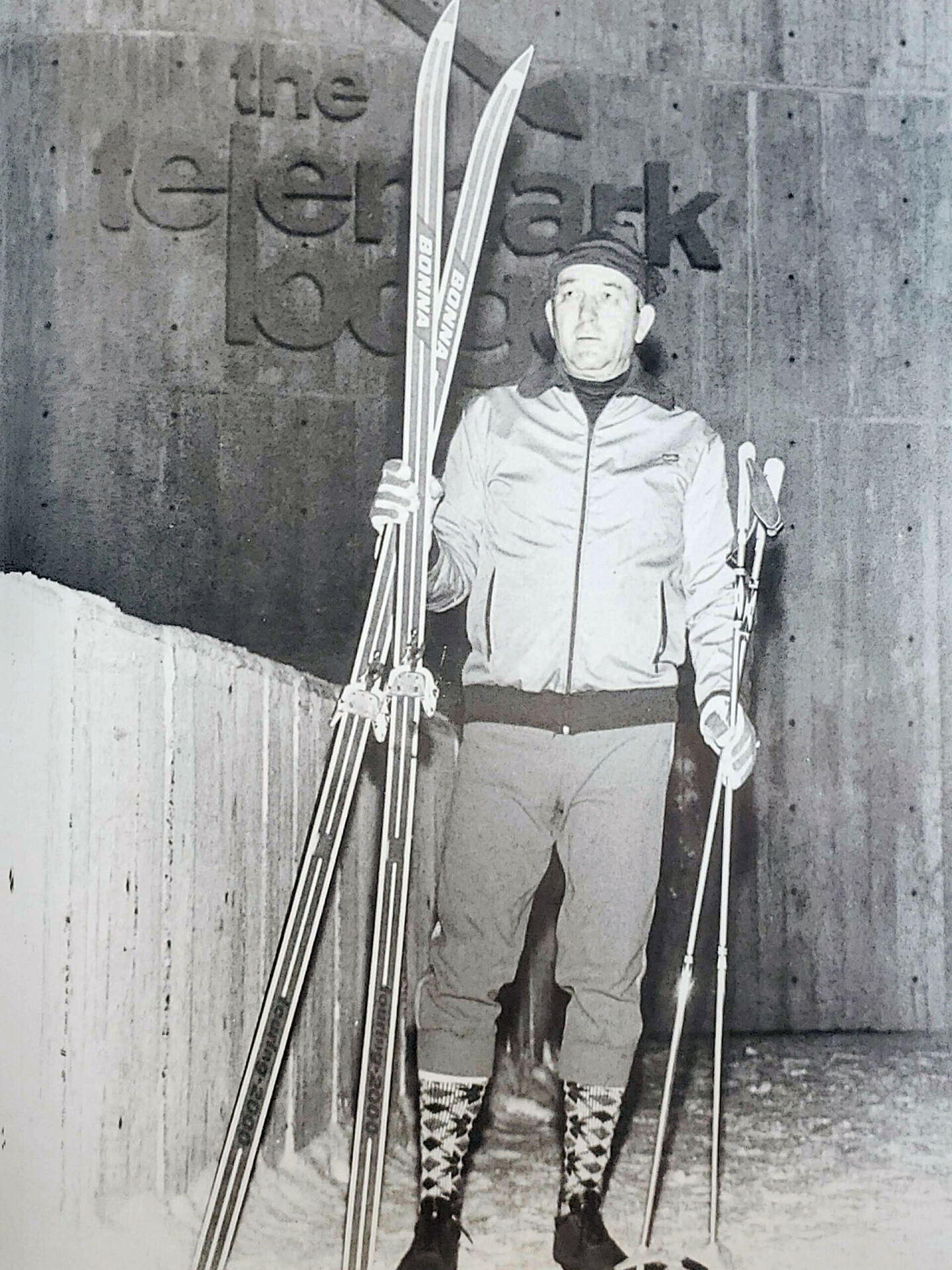

but here a certain ghost named Tony Wise, through a half century of hard-work, folded and stuffed all that is beautiful and good about the place into a singular word: Telemark.

With the vision Wise inspired alive and well through the Birkie, he can now watch over the rebirth, renewal, and continued legacy of the Northwoods that he helped create.

In other words, Telemark Lodge is an apparition now. Or rather, it will always be.

Ben Theyerl grew up in Altoona, has cross-country ski raced all over the country, and currently lives and breathes the sport while based in Crested Butte, Colorado.

He’s written about skiing at Fasterskier,

and about other things in The Brooklyn Rail,

Volume One, and BJ Hollars’ Hope is the Thing project (Available at the Local Store!).

Read Ben's personal story:

Growing up as a skier while Telemark Lodge was falling down

by Ben Theyerl