ARTS FEATURE: Prove Yourself

The arts have spent years proving their economic worth – will that ever change?

Kinzy Janssen, illustrated by Kat Wesely, photos by Andrea Paulseth |

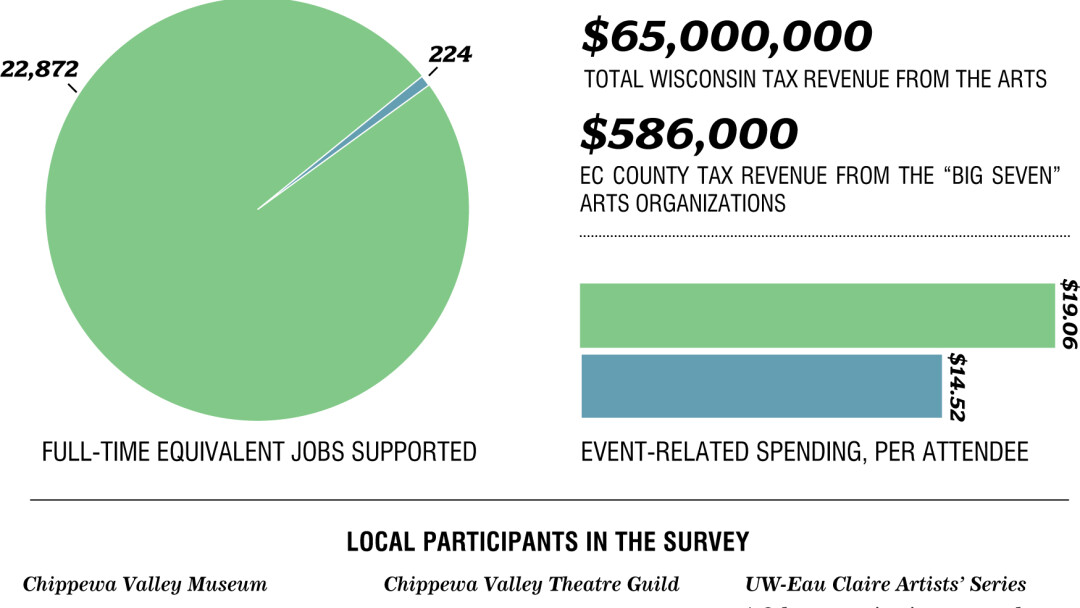

For the first time since Wisconsin arts agencies began conducting economic impact studies in 1987, Eau Claire County was examined individually and included in the inventory of a study. Thanks to Arts & Economic Prosperity IV (released this last June) we now have numbers that reflect actual dollar movement through our area’s arts channels. Previously, local non-profit arts organizations had to “look at data from other regions to see where [they] might fit in,” says Eau Claire Regional Arts Center Executive Director Ben Richgruber.

While the Wisconsin Arts Board sponsored the study on a state level, ECRAC took the reigns on Eau Claire County’s involvement, a role that came with a price tag of $2,400.

“It was money well spent!” says Richgruber. “Of course it would be great if it were free… but we were happy to do it.”

To gather the data, ECRAC paired with all the other “big players” in the non-profit arts sector by distributing audience intercept surveys. Of the 4,600 surveys collected in the state, ECRAC submitted over 900. Important to note is that none of the data was projected; they did not estimate figures for 100% of the arts-going public. “The information collected [shown at right] is based solely on the people who did respond, so it’s actually an understatement of how art is functioning in the area,” says Richgruber.

Getting Creative: Finding Funds

Statewide, non-profit arts organizations share the same boat – think of it as a big rig – that provides funding, primarily via grants. Last year, however, the Wisconsin Arts Board – part of the engine of that rig – lost its autonomy and was reduced to a program within the State’s Department of Tourism, consequently losing 67% of its operational budget. This put the rig on choppy waters.

“Sometimes I think, ‘I’ve already answered that question. Why are they still asking me?’ But people aren’t always paying attention.” - Anne Katz, Arts Wisconsin

According to Susan McLeod, the director of the Chippewa Valley Museum, CVM lost half of a Wisconsin Arts Board grant last year when the smoke cleared after the worst of the state budget cuts. Museum proponents watched the remaining half disappear this year. “When the State reduces funding, you have a cumulative impact. When you lose that ‘Supported in part by the Wisconsin Arts Board,’ people in your own community think, ‘Oh, it’s just a local group.’” McLeod thinks that a lack of official recognition (such as that coveted “supported in part by” tagline) causes locals to perceive community programs as trivial, so they’re less likely to jump in with their own dollars.

Still, our local “lifeboats” try to bear them afloat. The City of Eau Claire divvies up a Community Enhancement fund annually to local non-profit arts organizations. This fund (1.4 million in 2011) is available only for existing organizations, and the council continually examines internal financial information such as how much money the organization was allotted the previous year, how it was spent, and whether there’s any left over. The Community Enhancement Fund is generated by a room tax – the tax you pay when you stay at a hotel. Additional arts and culture organizations can compete for funding only after 56% has been given to Visit Eau Claire. As our official tourism bureau, Visit Eau Claire uses city money ($797,962 in 2011) to market all-things-Eau Claire, to help hone our image, and to foster economic growth. The organization then redistributes $31,000 annually to visiting conventions or special cultural events as they see fit. So organizations must make their appeal to the city council as well as the local tourism bureau.

“In a perfect world, arts wouldn’t be a separate budget line, it would be part of all city planning,” says Richgruber. Instead, organizations like ECRAC must provide factual evidence of economic strength (or, at least, economic stability) to justify the easing of purse strings.

According to Eau Claire City Council Vice President David Duax, the process of requesting money has become “abbreviated” in the last four to five years.

“It’s really been ratcheted down. They know we have less dollars to allocate. In the past it was almost like a parade; we had groups coming up to present, ‘well, we got $10,000 last year; we need $20,000 this year!’”

Duax says now groups are consciously controlling the amounts they ask for and focusing more on outside resources.

When studies like Arts & Economic Prosperity IV are published, it becomes easier to appeal to outside sources for grants. Numbers can actually “paint a picture” of Eau Claire County’s healthy arts spending climate and in turn grab attention and dollars.

“The Eau Claire Children’s Theatre has done a fabulous job of raising money,” says Duax. “And they’re not asking [the city council] for $10,000 anymore, they’re asking for $3,000.” When the economy starts gaining traction again, Duax says he will probably approach the funding process differently given the successes of independent fundraising.

“Emotionally, I know the thing I should do, but I have to prioritize other expenses. It requires that other sieve of ‘what should I do financially’?” asks Duax.

Behind The Numbers: A brief history of economic impact studies

Until the National Endowment for the Arts was founded in 1965, public subsidy for the arts was limited. According to a study done in 1992 by Anthony Radich entitled “Twenty Years of Economic Impact Studies of the Arts: A Review,” a complex network grew up around NEA [after only 15 years] that emulated the “long-standing service and advocacy networks that had grown up around other federal agencies.” Art was now a serious contender for government funding. When the Reagan administration began to stress government downsizing, Radich argues that the arts began to be characterized as “non-essential and non-legitimate function(s) of government that should be supported instead by a private sector.” Arts groups suddenly realized they needed to argue their worth based on low investment costs to the government and ample economic return. It was also during the ‘80s that arts organizations began to model themselves after businesses (in terms of administration, marketing, and fundraising) in order to survive in the marketplace. Another trend that occurred during this time was a dropping of artsy-sounding titles such as Director in favor of President or Chief Executive Officer. The names and practices have largely stuck. Like it or not, what has endured is the necessity and importance of attaching numbers to the value of arts groups. A new study is conducted in Wisconsin every few years now, the results of which are used to compete in the marketplace of government funding. The economic impact study is a method that has continually shown growth despite the slowing friction of the economy.

Until the National Endowment for the Arts was founded in 1965, public subsidy for the arts was limited. According to a study done in 1992 by Anthony Radich entitled “Twenty Years of Economic Impact Studies of the Arts: A Review,” a complex network grew up around NEA [after only 15 years] that emulated the “long-standing service and advocacy networks that had grown up around other federal agencies.” Art was now a serious contender for government funding. When the Reagan administration began to stress government downsizing, Radich argues that the arts began to be characterized as “non-essential and non-legitimate function(s) of government that should be supported instead by a private sector.” Arts groups suddenly realized they needed to argue their worth based on low investment costs to the government and ample economic return. It was also during the ‘80s that arts organizations began to model themselves after businesses (in terms of administration, marketing, and fundraising) in order to survive in the marketplace. Another trend that occurred during this time was a dropping of artsy-sounding titles such as Director in favor of President or Chief Executive Officer. The names and practices have largely stuck. Like it or not, what has endured is the necessity and importance of attaching numbers to the value of arts groups. A new study is conducted in Wisconsin every few years now, the results of which are used to compete in the marketplace of government funding. The economic impact study is a method that has continually shown growth despite the slowing friction of the economy.

Keeping the Story Fresh

Hasn’t a multitude of national economic impact studies shown that the arts can hold their own amongst other, more “mainstream” industries? That they are integrated in our social and economic fabric, and are not a “frill?”

Anne Katz of Arts Wisconsin has insight on the cyclical nature of these types of studies and how the voting public, as well as legislators, receive them – and how that dreaded “frill” label can be erased.

“Slowly but surely we’re addressing those misconceptions. It goes in cycles. There’s a flurry of activity and then things change. Sometimes I think, ‘I’ve already answered that question. Why are they still asking me?’ But people aren’t always paying attention,” she says.

What do locals like Richgruber make of this justify, wipe-the-slate-clean, justify approach? It’s simply necessary.

“I would say I don’t have to defend what I do on a daily basis. But when it comes time for the city to allocate funds for us – that’s when we have to meet them head-on. People in government… they might support the arts in theory…but they still need numbers,” he says.

Eau Claire City Council President Kerry Kincaid confirms this. “It’s not just that we love the arts and ‘Kumbaya’ and isn’t that wonderful… we need cold hard facts,” she says.

And it’s not just the arts that have to keep fresh numbers circulating. Katz says most industries have to keep advocating for themselves, especially because “tight budgets” are ubiquitous in this recession.

“If anything, having to do these studies shows that we are more like other industries,” says McLeod. They’re a worthy cause, but their time-consuming nature presents a bit of a pickle. In order to be able to spend more time and money on cultural programs, non-profit directors like McLeod must spend time (and sometimes money) on the studies that spawn financial support. “Filling out the surveys… I’m always exhausted. It always takes three to four times longer than they say it will. But if you don’t suffer a little, you’re never going to get that information in the end.”

The Art of Non-stop Advocacy

Arts advocacy often wears a political button, like it or not. As such, Katz and Richgruber have made conversing with legislators part of an everyday routine.

“My state representative Mark Pocan lives next door and I write him formal letters, but I also talk to him in the yard,” says Katz.

Richgruber echoes the importance of a more casual, on-the-spot initiative. “It’s all up to the people in Madison at any given time… But we are all responsible. Whenever we get a chance to send a letter or shake a hand of whoever controls the purse strings, we need to do these things,” Richgruber advises.

While economic impact studies “give the arts a voice” conceptually, the numbers are still silent until someone takes a highlighter to them and explains their context.

“We are interested in stats and data… but we have to rely on organizations to have deep expertise and to prove this or that about their impact,” says Kincaid.

Arts organizations agree that because the value of arts is so multi-faceted, one cannot only present numbers. They cannot ignore the “art is part of what makes us human” component. As social activist and writer Eva Cox says, “We don’t live in an economy, we live in a society.”

“We are always looking for one-on-one meetings with legislators so people can talk about their passion for the arts,” says Katz. “Social media is also an important tool to be able to tell stories through pictures, descriptions, and video… and to have an ongoing conversation.”

Kincaid says emotional appeal is important, too. “They… have to come right before the council and it’s not just, ‘Oh, someone came from Fond du Lac and spent $5, which multiplied to $15. We have to rationalize and legitimize our choices with… these things that can be hard to measure… but we know the arts have some direct positive impact on the people in our area.”

Arts advocacy went public in South Carolina last month after Governor Nikki Haley vetoed all funding for the Arts Commission and an additional $500,000 for further grant distribution. Opponents responded with a highly visible campaign at the state capitol where participants played music, danced, and painted. The House and Senate voted July 17 and 18, respectively, to override both vetoes and restore funding. The Arts Commission was able to swing its doors open once more.

“We advocate for the arts by doing the arts – getting people involved and having them experience it,” says Richgruber.

Putnam Heights Neighborhood exhibit.

Moving Forward: Future Studies

The three non-profit arts leaders I talked with expressed the definite necessity of the continuation of these studies on a national, state, local, and even internal level. Richgruber likes having up-to-date numbers because they are only sharpened every few years, while Katz is optimistic about adopting highly efficient information-gathering systems like those used by other states, which provide a more constant flow of stats. Ultimately, they believe that the so-called divide between the world of economics/government and the world of arts/culture must be traversed.

While there will never be numbers to measure the level of enthusiasm within the field of non-profit arts and culture, it appears to be an impressive amount. “The major players in the arts industry are very enthusiastic, very overwhelmed, and very committed, given the challenges of the historic recession,” says Katz.

Recession or not, organizers will crunch numbers with the left side of their brains for the opportunity to develop their right halves.

Confluence Project: Bringing Ideas - and Potentially Dollars - to Life

The Chippewa Valley Museum’s 2010 cultural survey, known as “The Good Life,” collected reams of written responses concerning Eau Claire’s current cultural amenities. These would later help galvanize plans for The Confluence Project, an $85 million riverbank hub announced May 15 which will boast a community arts center and a separate living and learning space for UW-Eau Claire students.

Though the Good Life’s approach was more opinion-based than most economic impact studies (which thrive on hard facts), numbers were still used to garner support and funding.

Gathered by CVM, the survey’s comments shed a spotlight on the county’s collective desire for some kind of “large venue.” Independently of one another (and without prompting), 77 respondents made mention of the necessity for a convention center, arena, modern/new cultural arts center, performance/concert space, civic center, or some combination of the aforementioned. Though the Confluence Project will only fulfill the “new cultural arts center” contingent, it’s clear that it will meet the needs and goals of scores of Chippewa Vallians, whether they be participants or audience members.

“People might say, ‘It’s not the time. It’s time to bring growth through factories.’ Well this is a type of factory...” - Ben Richgruber, Eau Claire Regional Arts Center

There are still budgetary considerations (especially operational) to examine before ground is broken at the confluence of the Eau Claire and Chippewa rivers in 2014. But the kinds of statistics gleaned from Arts and Economic Prosperity IV can be constructive even after the green light is glowing.

“People might say, ‘it’s not the time. It’s time to bring growth through factories.’ Well, this is a type of factory,” says Richgruber, referring to the revenue and job creation resulting from successful non-profit arts organizations. “Mostly we’ve gotten two thumbs up. It’s ten to one positive over negative. But [city and county official’s] questions and concerns are legitimate,” he says.

What worries some is the transition of the proposed Haymarket site from tax-generating to non-tax generating property.

Clear Vision Eau Claire, a visionary group that focuses on long-term development and citizen involvement, is optimistic. Clear Vision board member Mike Rindo says the example set by development on North Barstow (restaurants, retail, and apartment complexes) is a good indication of what will happen on South Barstow – possibly on an even higher scale. “People think it has great potential… It will be a major attraction and gathering place, and a regional attraction for people over in Minnesota,” he says. Rindo explains that their budget models are realistic, and thus hope is founded in viability.

Kincaid is excited about the uplifting effect the project will have on its radius. “I’ve never been around a performing arts center that causes the location to degrade, whether it’s New York City, Minneapolis, or Morehead, Minn.,” she says. “It causes a lively and vibrant spirit to rise up in invest in the private sector. With reasonable public investment, there will be a multiplier effect.”

Kincaid is also heartened by Eau Claire’s particular set of experiences.

“To me, we’re the perfect city to make such a venture go. We have deep experience in these successfully shared spaces: the Municipal Pool, Carson Park, Hobbs, which has four user groups,” she says. “I can’t imagine that it wouldn’t also be a successful center in a shared space,” she says.