Cultural Backdrop

how a year-long stint in China helped reaffirm my faith in democracy

Kinzy Janssen, illustrated by Catlin Felix Kramka |

In February of 2011, I was sitting at a computer in Shenyang, China when I stumbled upon a front page story on the BBC news webpage depicting a capitol (my capitol! my gut realized) filling with thousands of people and just as many hand-painted signs. Ironically, the reality of that distance – all those miles – suddenly magnified the power of a democracy against the cultural backdrop of China.

As part of my job as a native English teacher, twice a week I spent four hours in a classroom with a single adult Chinese student. These 20 to 50-year-olds were engineers, operators, and managers at the Michelin factory who needed intensive English-language instruction before shipping off to an American factory for training. Topics ranged far and wide, depending on the comfort level of the student. (The NBA, American weddings, and whether or not we could cook/drive/haggle in China emerged as their favorites). I never brought up politics, but sometimes they did.

It is one thing to hear about China’s Great Firewall in theory, but it is angering when the error message pops up at your fingertips.

“What do you think of Chinese government?” one student named Manny asked. My eyes wandered to the upper corners of the classroom, half-expecting there to be recording devices, or a suddenly-materialized spy. I answered slowly, admitting my suspicion of shoddy workmanship on government projects such as trains and subways.. But this was the green light Manny had been waiting for; he now spoke frankly about the helplessness his fellow citizens felt toward the regime. He told me that “no one” believed their government to be healthy, and that “everyone” discussed these matters in the safety of their own tightly knit circles. To act on their feelings would be to risk house arrest or dangerous threats like Chen Guangcheng, a recently-escaped Chinese activist. Manny’s tone was bitter – how could an American understand this climate of silence?

Though living in a foreign country for a year constitutes a role somewhere between resident and tourist, I experienced this “climate of silence” almost daily through Internet censorship. It is one thing to hear about China’s Great Firewall in theory, but it is angering when the error message pops up at your fingertips (sorry: the server has timed out) when you try to access YouTube, Facebook or Twitter. I learned that, for Chinese citizens, it is only possible to access the Internet by first plugging in the equivalent of a social security number, thus surrendering all privacy.

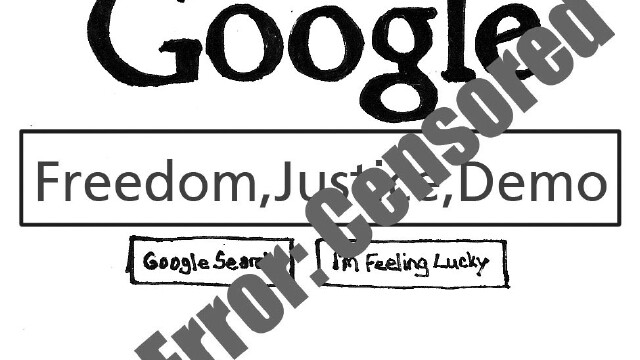

Add to that China’s tepid relationship with Google. It seemed that after an arbitrary number of searches (three? five? ten?) the server would time out, halting my laughably innocent image searches for “cow,” or “tree” intended only for homemade flashcards. Searches that always resulted in a “timed out” message on Google were “Arab Spring revolutions” and “Tiananmen Square massacre.” Sadly, many of my students believed Google to be a faulty (and thus inferior) search engine compared to China’s BaiDu: They didn’t realize the government was orchestrating it.

Not surprisingly, the internet, especially social media platforms, has shaped uprisings in recent years, connecting like-minded individuals who went on to organize democracy-fueled protests. Syria is having a rough time of it, to say the least, arguably because the government has cracked down on online networking. Is social media essential to a democracy? No. But free and open information is.

Whatever your reaction to the recall’s conclusion in Wisconsin, I will always have faith in a country where discussion and dissemination of knowledge is not only allowed, but encouraged. Last weekend, I volunteered to canvass a neighborhood on the north side. I was given a list of residents who were believed to be friendly to our campaign – the goal was to make sure they followed through and voted, or to steer them back if they had “gone astray.” As I passed one particular house (it wasn’t listed on my route), a mustachioed man sauntered down the driveway. “You’re going to skip me?” he asked, mock-incredulous. “Whaddaya got?” he teased, going all fisticuffs on me. I laughed, then gave him the same “schpiel” as everyone else. Though he wouldn’t confirm his candidate of choice, I was really amused: he’d felt slighted that I wasn’t going to involve him!

Then it hit me: American democracy is based on inclusion despite division.

Before you accuse me of touting democratic ideals too naively (There are flaws! Weaknesses! Gaping holes! you say), I say, you’re right. But we’ve been given the right to discuss and act against those flaws. And while I enjoyed my time in China, it was there that I developed a newfound appreciation for the ballots and gatherings and the wonderfully opinionated words I’ve had the right to enjoy all along. Contrast makes the heart grow fonder.