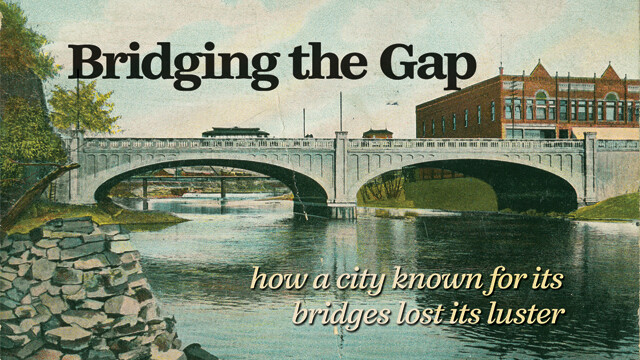

Bridging the Gap

how a city known for its bridges lost its luster

Emily Kuhn, photos by V1 Staff & Contributors , Andrea Paulseth |

Twenty-five years ago, Eau Claire artist Michael Peterson snapped a photo of the Dewey Street Bridge from the bottom looking up. The idea for that particular angle came from his fondness of fishing underneath the bridge as a child, and he was inspired to capture the view as an adult years later while taking a photography course at UW-Eau Claire. Now the only remaining arch bridge in Eau Claire, the Dewey Street Bridge represents more than a memory from childhood – it’s a testament to the city’s history that Peterson hopes people will take time to appreciate as the city continues to change.

“Bridges have always been critical to Eau Claire. There’s a nostalgia, a history to them. … Now, I see those aesthetics coming back ...” – EC Public Works Director Brian Amundson

“You just think that stuff will last forever when you see it there – you don’t think about it being gone,” Peterson said of the picturesque arch bridges that crisscrossed the city until the 1970s. “The new ones are in better shape, so it’s clear why the old ones had to come down, but … this is our history. These bridges help the community stand out.” In fact, in our search for images of the city’s historic bridges we found that the vast majority of them at Chippewa Valley Museum are in fact postcards. Proof that these were the picturesque vistas of the city, the things that defined the area and compelled visitors to purchase an image of and proudly send it to loved ones elsewhere. Similarly, the Court’N House’s visual slideshow of our city’s history is inundated with bridge pictures in the 70s – the last moments of the bridges before being torn down, the process of them being torn down, and then the construction. Missing from the slideshow are images of the end result. We can only guess that those with cameras recognized the underwhelming result. So what happened? How did a city known for its bridges change over time?

Remodeling Time

Calling Eau Claire “a city of bridges,” Public Works Director Brian Amundson explained that although the past three decades have seen the remodeling of older bridges into stronger steel and cement ones, the aesthetics that were so often the first feature observers noticed about older bridges will continue to be considered when constructing new ones. However, the most important factors any city considers when remodeling or constructing a bridge has been (and always will be) cost – cost, and the carrying capacity of the river underneath. As Amundson explained, concrete and steel tolerate compression and tension a lot better than the wooden arch and truss bridges that were popular in the early 19th century. With the development of concrete and steel, particularly the I-Beam (a type of load-bearing beam whose cross section is shaped like the letter ‘I’), cities were suddenly able to produce stronger bridges that could span much farther distances than previously realized – and they could be produced at a lower cost.

Lookin' Good Ain't Cheap

Lookin' Good Ain't Cheap

Using rough estimates of costs per square foot provided by Ayres Associates bridge engineer Dave Pantzlaff, and the Engineering News Record Construction Index to calculate the current cost of building arch bridges, Amundson determined the current costs of constructing a concrete or steel beam bridge versus an arch bridge. It would cost $4.2 to $8 million to construct a concrete beam bridge with a deck area the size of the current Madison Street Bridge (41,481 square feet), depending on the condition of the foundations and whether they’d need to be replaced. Comparatively, it would cost $14.5 million to construct a concrete arch bridge with a deck area of that size, he estimated. Similarly, it would cost about $1.3 to $2.6 million to construct a concrete beam or steel beam bridge with a deck area the size of the current Dewey Street Bridge (12,984 square feet), while it would cost $4 to $4.5 million to construct a concrete arch bridge with a deck area of that size, he added. “The beams that we created starting from the 1920s and on allowed us to have a more efficient section that’s cheaper to build and can span a longer distance,” stated Amundson.

Eau Claire Bridges, Then and Now (click to zoom)

Go With the Flow

The carrying capacity of new concrete and steel bridges was also much higher than the old arch designs. According to Amundson, any obstruction you put underneath a bridge restricts the amount of water that can flow and causes it to back up on one side. This factor is important in the analysis of flooding, or the amount of water that you’re trying to flow underneath a bridge. Since the old arch bridges featured large curved sections that jutted out underneath the bridge, they restricted more water from flowing underneath than the thinner beams used on modern I-beam bridges. The Madison Street Bridge is a good example of these factors and the difference they make in modern construction. Built in 1923 and reconstructed in 1977, this bridge’s new design was a prime example of the “build it as efficiently and as cost-effective as you can” motto that dominated the construction industry from 1965 to 2000, according to Amundson. The charming arches it used to feature simply took longer to produce, used more materials, and blocked more water from flowing underneath than the sleek, “minimalist” design and steel beams it now features. “It’s been an evolution of the industry and our structural understanding of technology,” said Amundson. “We went from only spanning little places to being able to span bigger places to I-beam structures that replaced the arch.”

Returning to Former Glory?

Notice the fancy stone work including turrets.

The Dewey Street Bridge over the Eau Claire River is the only span left that retains the arched aesthetic. Built in 1931 for a mere $67,700, whether or not it will meet the same fate as the Madison Street Bridge has yet to be determined, and Amundson added that the city is only planning on repairing the base of its arches this year. But its future design, whenever needed, could very well feature the aesthetic details that were left out of its counterparts’ redesigns as attention is once again being paid to the aesthetics of bridges. “Technology has led to advancements in pouring concrete, where the use of architectural form liners can make cement look like rock or limestone; you can even stain it,” said Amundson, pointing to how the cement used for the bridge over State Street was made to resemble stone. He said officials are also already considering similar details for the Water Street Bridge, which is due to be replaced in 2014. Early models of that bridge show railings that mirror old-fashioned designs, with tall arches and layered embellishments. “Bridges have always been critical to Eau Claire,” said Amundson. “There’s a nostalgia, a history to them. … Now, I see those aesthetics coming back: architectural enhancements, treatments to the railings, etc. … The technology of spanning a space with an arch probably is not, but the decoration of the top is.”