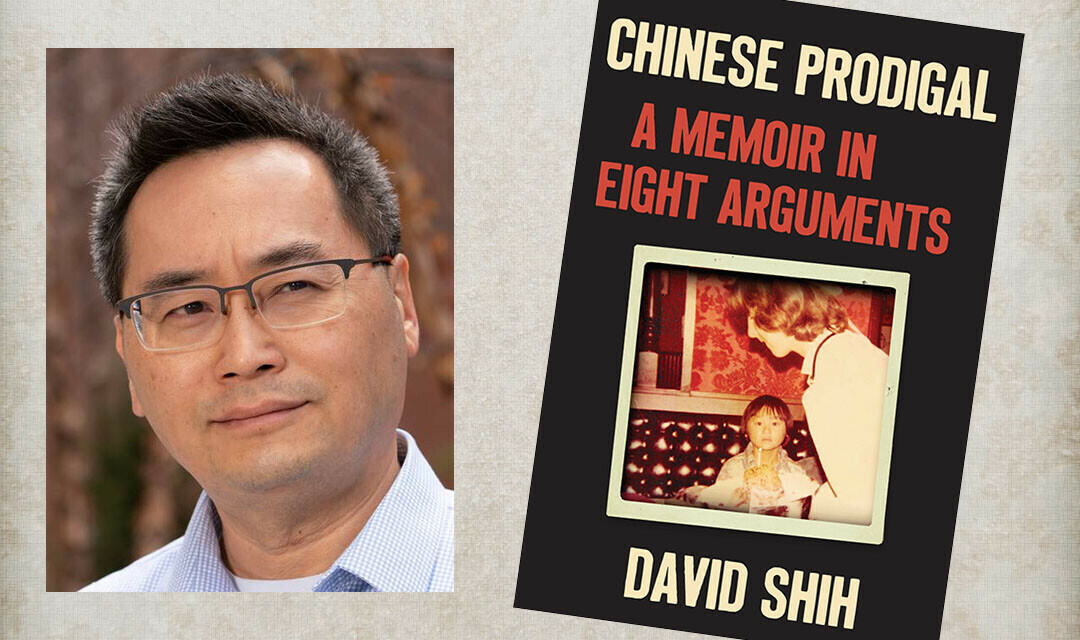

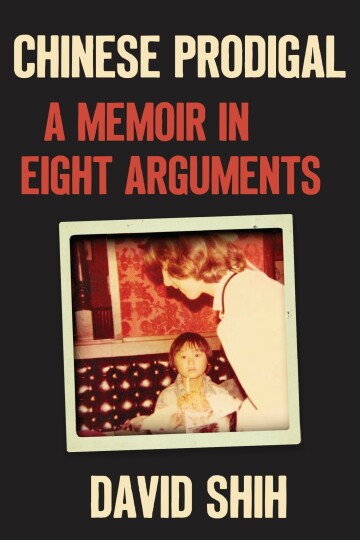

‘CHINESE PRODIGAL’: UWEC Professor’s Memoir Examines Life, Race in America

David Shih looks at what it means to be Asian American

David Shih’s new memoir is a searing commentary on race in America, especially what it means to be Asian American in a country that is often seen as a neat division of black and white cultures. The memoir begins with some deeply personal moments of family history which produce deep reflection, and then broadens into analysis on many relevant issues of our time including the rise in anti-Asian American violence following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chinese Prodigal: A Memoir in Eight Arguments, begins with Shih, a professor of English at UW-Eau Claire, grappling with the loss of his father to complications produced by diabetes, but more importantly, it is an entry point into a reflection on his relationship with his father, his Chinese heritage, and his belated arrival to see his father after he suffered a stroke. Shih remembers how miserable his father was in the hospital and how ardently he hoped his son would take him home. Shih confesses, “The truth is that I was afraid of what seeing him in the hospital would force me to do, which was decide whether to stay in Texas and help him through an uphill recovery or else an undignified decline.”

Later in the same chapter, Shih wonders what he would say to his father in a meeting after death. He writes, “The child would start by saying that this country turned him against his parents just by sending him to school. He learned to look upon the parent falsely, as the powerful did. … At the end, he would say he did it all because of a late folk tale that they both knew, which was ever the promise of a better life.” As the memoir proceeds, Shih attempts to ponder deeply on questions of his alienation from his immigrant parents, his father’s decision not to teach the children Cantonese to facilitate their American assimilation, and Shih’s decision to become an English professor and move to Wisconsin, abandoning his father’s traveling business in Chinese artifacts, both of which increase the distance between his parents and himself.

Another major theme that the memoir covers is Shih’s experience of marrying a white woman and parenting a biracial child in Eau Claire, where he is a professor of English, and which is still a town of limited racial diversity. From his early experiences of dating white girls in high school, the sense of anxiety persists, even a fear that he might be thought of as a kidnapper for carrying a white-presenting child. There are also complicated interactions with his wife’s family, especially his father-in-law’s own history of serving in Vietnam. To the credit of Shih and his wife, Robin, the couple are able to negotiate many thorny issues, without losing the goodwill and warmth of the extended family.

While the personal part of the memoir touches on many moments of othering or microaggressions that Shih encounters in everyday interactions, the larger world and its politics amplify the sense of fear and precarity of belonging. Shih devotes a chapter to the episode of the killing of Vincent Chin, in 1982, close to where he earned his Ph.D. at Ann Arbor, Michigan. Chin was a victim of a hate crime in which he was mistaken as Japanese and someone responsible for stealing American auto manufacturing jobs. Shih became aware of Chin a decade after his death, but it is a crucial moment of coming into consciousness as an Asian American and realizing that what he shared with Chin was “our vulnerability in America.”

Shih astutely deconstructs the myth of the model minority to reveal how quickly the model and problem minorities can shift shape. One example is the recent FBI scrutiny of Chinese scientists suspected to be trading security secrets with the Communist Party in China.

Another example is the violence and verbal abuse that has been targeted at Asian Americans ever since COVID-19 was termed the “Chinese virus.” Even though Asian Americans such as Shih’s parents come to the U.S. as immigrants hoping for a better life and try very often to assimilate, often eschewing markers of their ethnic identity, their acceptance is conditional, and they are often on the verge of being exiled. The last chapter focuses on a lesser-known episode in the Black Lives Matter-related police shootings. Shih examines the 2014 incident of Peter Liang, a Chinese American police officer who was tried and found guilty of homicide for the shooting of a black man, Akai Gurley, in New York. Shih identifies the terror of Liang, during his trial, and although supportive of the sentencing, he wonders if Liang would have been found not guilty if he had verbalized his fear of a threatening black body in a dark stairway, the defense that many white police officers had used effectively.

David Shih’s memoir is provocative and brave in asking tough questions of himself and his readers. He examines many hot-button issues such as affirmative action and the banning of books teaching Critical Race Theory to unpack the multilayered aspects of America’s racial past and how Asian Americans have ignored racial struggles only to realize how precarious and conditional their own belonging can be.

Chinese Prodigal by David Shih will be officially released Aug. 15 by Atlantic Monthly Press as a hardcover and e-book. It’s available through numerous online and in-person booksellers.

The L.E. Phillips Memorial Public Library in downtown Eau Claire will host a special event featuring Shih on Tuesday, Sept. 12, from 6:30 to 7:30pm in the Riverview Room. Shih will read from his new book, Chinese Prodigal: A Memoir in Eight Arguments, with conversation to follow. This program is co-sponsored by the Chippewa Valley Writers Guild.

Lopamudra Basu is a professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Stout.