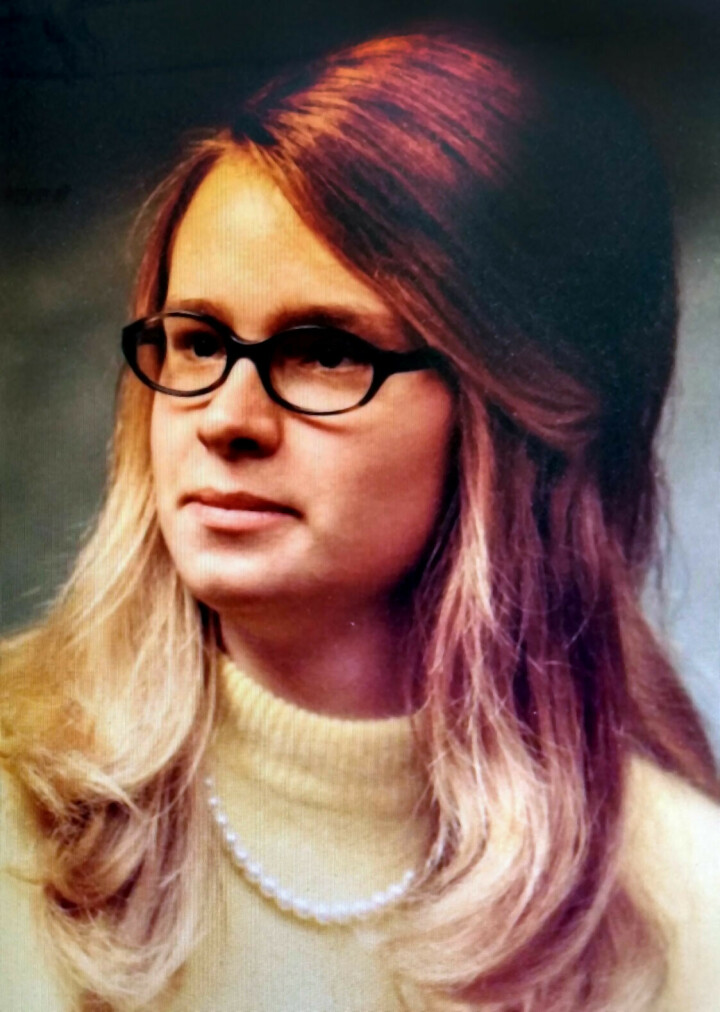

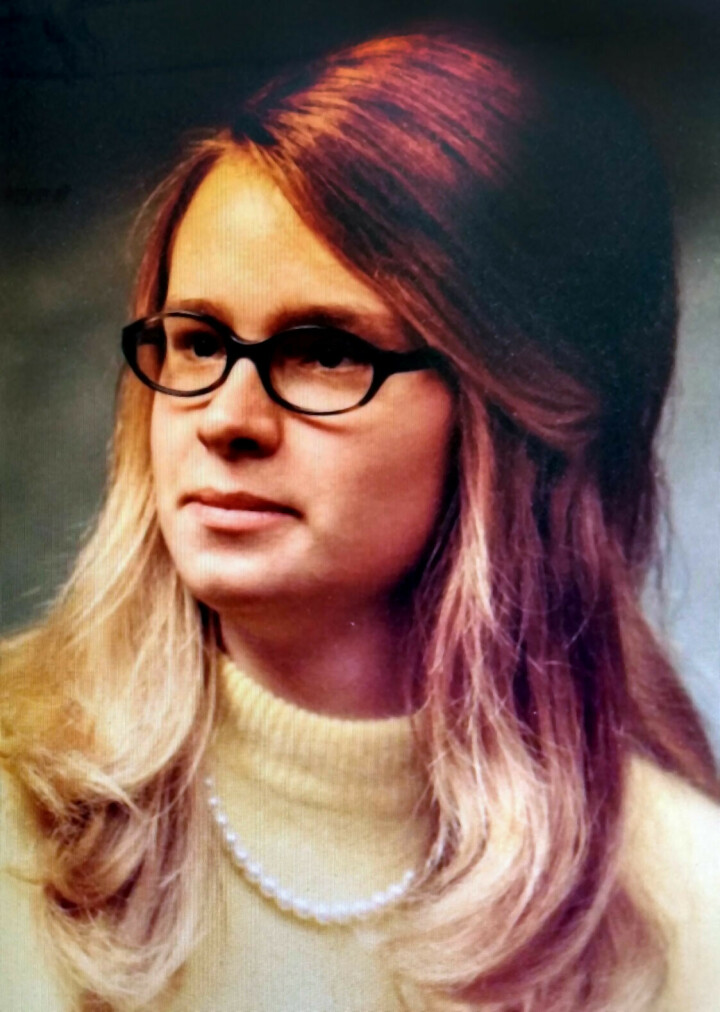

Remembering Marilyn

The joys and struggles of one Eau Claire woman who died without a home

This article is a supplement to the feature story: No Place to Call Home.

For the last two years of her life, Marilyn Roeber spent many days and nights on a metal bench at the 400 block of South Barstow Street in Eau Claire, often speaking with passersby. Not everyone was willing to engage with Marilyn, who was usually surrounded by various bags, blankets, and often a sleeping bag she carried with her.

But when they would, she would discuss just about anything with anyone.

“Any time people would sit down and talk with her, Marilyn would take part in conversation,” recalled Julie Smith, office manager at Valleybrook Church, located near the bench Marilyn often occupied. “She loved to talk, and she would talk with anyone who would listen.”

Conversations with Marilyn don’t happen anymore. Eau Claire police discovered her dead on that bench on June 16 after receiving a call that she was unresponsive. Marilyn, 66, spent nearly three consecutive days and nights on that bench before dying there.

According to the police report, Marilyn’s death wasn’t suspicious. There were no signs of trauma, no signs of drug or alcohol use.

She’s just gone.

A month after Marilyn’s death, Smith still finds herself looking out her office window to check on the woman she befriended. Smith got to know Marilyn some years ago, when Marilyn began attending Valleybrook. They spoke almost daily, often multiple times each day.

Being Marilyn’s friend wasn’t easy. Those who knew Marilyn said navigating her strong-willed, sometimes combative personality could prove difficult, they said. But Marilyn had a kind side, too, friends said. She wanted to engage with the world around her, wanted to connect with people.

“I cared about her,” Smith said. “She needed help, needed someone to listen to, and that was something I could do.”

Numerous people, including members of Valleybrook and other churches, downtown business owners, and passersby, reached out to her in various ways. On many occasions, Smith and others said, they tried to link Marilyn to help through the Eau Claire County Department of Human Services, other counseling services, medical care, and other assistance. But Marilyn was adamantly opposed to those efforts, they said.

“There were a lot of people who cared for Marilyn, who did what they could to help her,” Smith said. “It was frustrating at times, because you could see she needed the help. But she wouldn’t accept it, and we couldn’t make her.”

Marilyn was adopted as a young girl, according to one of her relatives, and grew up in Augusta, where she graduated from high school and lived for quite some time. The relative, who wished to remain anonymous, said Marilyn’s adoptive parents provided her a loving, safe environment.

Despite those happy times, Marilyn sometimes struggled to get along with others, the relative said, prompting questions about what may have happened to her before she was adopted.

After graduating, Marilyn lived with her parents for quite some time. Eventually, she moved to Eau Claire, and finally into a downtown apartment with a roommate. Then, in spring of 2019, their landlord notified them that renovations were needed on the building, and they would have to move.

Shortly before they had to leave the apartment, Marilyn’s roommate died. Suddenly, Marilyn found herself without a home. People familiar with Marilyn’s situation said she spent time at Sojourner House before she was no longer allowed to stay there. She took up residence on her favorite bench and sometimes spent time living in motels when donors would pay for her to do so. Most recently, she stayed at a motel on Eau Claire’s southwest side before returning to her familiar bench on June 14.

On June 16, when Smith saw the ambulance arrive to check on Marilyn, she felt both worry and a sense of relief.

“I thought, finally, Marilyn will be taken somewhere where she will get the help she needs,” Smith recalled.

Moments later, Smith learned that Marilyn was dead. Her heart sank.

When I received a phone call from a friend notifying me of Marilyn’s passing, my heart hurt too. Her passing prompts memories of other homeless people I have known in Eau Claire who have died because of conditions they have faced living on the street.

The loss of Marilyn and others like her in our community leaves me uneasy. My mind — like countless others — is flooded with questions: Shouldn’t deaths like Marilyn’s be preventable? Don’t we have a safety net for people in similar situations? How do we provide more resources to better assist people struggling with homelessness — to prevent them from becoming homeless in the first place.

Most importantly, though, I wondered: What could I have done to prevent Marilyn’s death?

Addressing mental health issues seems particularly challenging. Current law allows people to decide for themselves whether to receive mental health treatment and other services, even if experts would agree that oftentimes, because of their state of mind, certain people are not able to make sound decisions. They are committed only if they are deemed an immediate threat to themselves or others.

Those regulations are well-intended, but they can leave people like Marilyn in situations that can hinder them and even lead to death, said Anna Cardarella, CEO of Western Dairyland Economic Opportunity Council, which works with homeless people and others in need in four west-central Wisconsin counties.

“We have clients who simply cannot care for themselves,” she said, “but they have the right to make decisions, even if those decisions seem like poor decisions. In some cases, you have to ask the question: Is someone’s autonomy worth their life?”

That question and others related to mental health and homelessness don’t have easy answers.

But that doesn’t mean that we — as a community — shouldn’t grapple with them. We need to decide, collectively, if we care enough about homeless people, and others at risk of becoming homeless, to do more to address the situation.

We need to decide if we’re OK with homeless people — our neighbors, friends, people in our community — dying in our midst. If we’re OK with looking the other way, with being too busy with the rest of our lives to take action. We need to decide if we’re willing to let Marilyn’s death pass by, ignoring her death instead of using it as an opportunity to spur discussion that could perhaps lead to the prevention of future deaths.

Smith, for one, hopes some good can come from the loss of her friend. She hopes Marilyn’s death prompts community forums about homelessness, mental health, and other related topics, discussions she hopes lead to action.

“If we can spur some of these conversations,” Smith said, “then Marilyn’s death won’t have been in vain.”