The Oracle of Eau Claire

the secret history of a Ouija board gone awry

BJ Hollars, photos by Andrea Paulseth

On a Saturday in September, I found myself inside a stranger’s house. I wasn’t alone, but joined by a small parade of fellow thrifters – each of us having been lured inside by the estate sale sign displayed along the tree-lined walkway.

Never one to miss out on the chance to rifle through another’s possessions, I’d slipped inside the doorway. No matter that the house bore a striking resemblance to the Amityville Horror House. It was a crisp fall morning, birds were singing.

What could possibly go wrong?

I began on the first floor, flipping through the entirety of a record bin and tucking a few selections beneath my arm. Then, I started up the stairs, distancing myself from the crowd.

To the untrained eye, the mood inside that house must’ve seemed funereal – Doesn’t an estate sale imply that someone has died? But we bargain hunters were not there to pay respects; we were there to acquire. After all, where else could we get such low, low prices on a pair of second-hand shoes?

Or boardgames, for that matter – a stack of which I found in the upstairs walk-in closet. Given my children’s love of games, I figured I was in the market for Trouble or Chutes and Ladders. Instead, my eyes fell upon a different game.

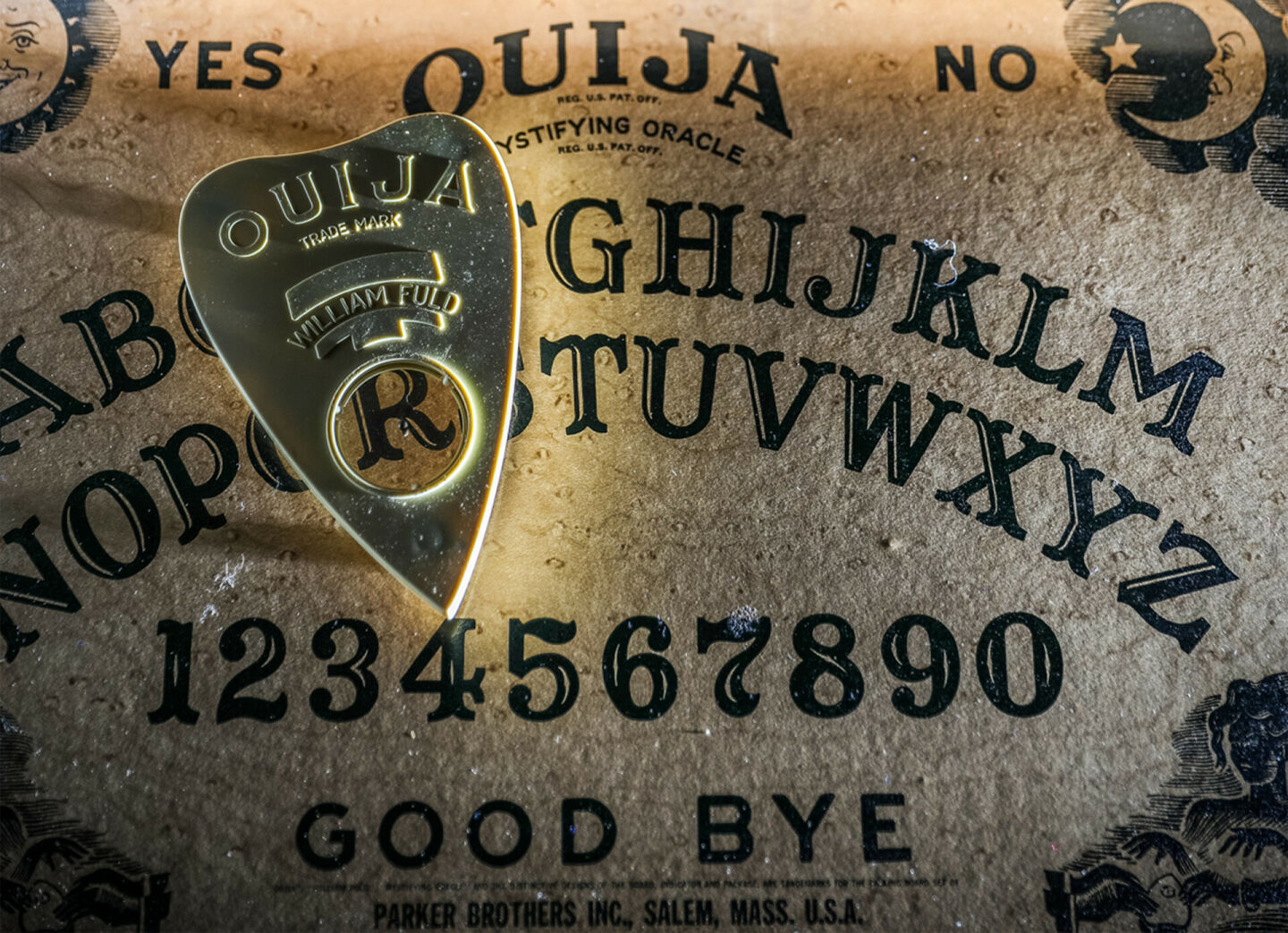

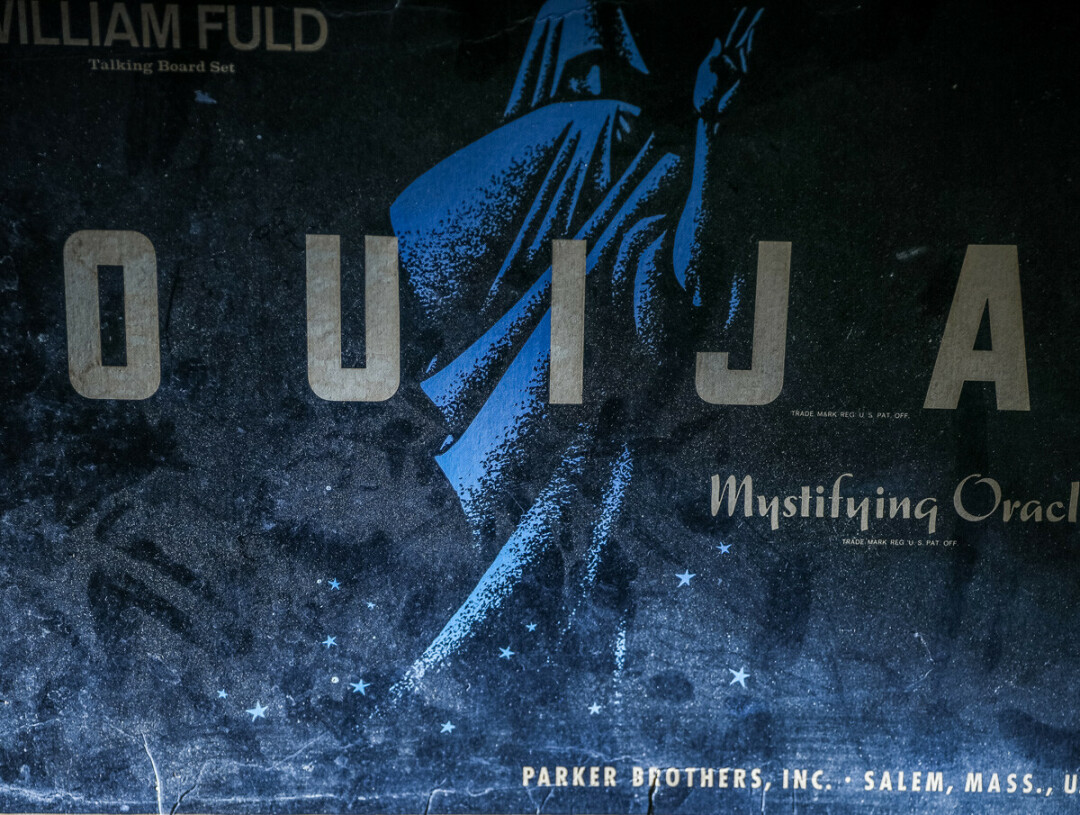

I plucked it from the pile, astonished by the game’s cover art – a spectral figure shrouded in a robe.

In the box’s upper left corner: “William Fuld Talking Board Set.”

In the bottom right: “Parker Brothers, Inc. • Salem, Mass., U.S.A.”

And smackdab in the middle:

Removing a few dollars from my wallet, I wound my way down the stairs toward the checkout table. I quickened my pace, drawing the attention of my fellow thrifters, who, upon glancing the board half-hidden behind the records, widened their eyes.

Jealousy or horror – who can say?

Days after purchasing the Ouija Board at the estate sale, a mutual friend informs me of the board’s previous owners: Bob Carr and Roger Groenewold, both 77, who, in fact, and are very much alive. They’d served as the board’s caretaker for over half a century, though upon recently moving to a new residence, they’d left their board at the mercy of their estate sale.

“So where did the board come from?” I ask one afternoon over Chinese food.

“I guess we bought it in the late ’60s,” Roger says. He turns to Bob for confirmation. “The late ’60s, wouldn’t you say?”

“I was acting,” Bob says, “and weren’t you in Milwaukee?”

They work through life’s timeline in reverse, eventually settling on ’68 or ’69 as the year they purchased the board at a since shuttered store here in Eau Claire.

“They were used a lot at college parties,” Roger explains. “At that time everyone was into it. Bad wine and Ouija boards,” he smiles. “It made for good entertainment.”

Yet for Bob and Roger, the board continued to make appearances at social gatherings well beyond their college years.

“Sometimes we’d host a dozen people, at least,” Roger says. “Probably a quarter were nonbelievers, a quarter were into it, and the others were mixed.”

Some nights the spirits seemed wholly disinterested in moving the planchette, but other nights, the opposite was true.

”

The most dramatic example, they tell me, was the night their coffee table walked across the room.

“You mean, the board moved?” I try.

“No,” Bob says. “I mean the table on which the board was sitting literally walked across the room.” He places his hands in the air to demonstrate, moving them in tandem to represent the halting motion of the table legs.

The most dramatic example, they tell me, was the night their coffee table walked across the room.

I drop my forkful of rice.

“You mean, the board moved?” I try.

“No,” Bob says. “I mean the table on which the board was sitting literally walked across the room.” He places his hands in the air to demonstrate, moving them in tandem to represent the halting motion of the table legs.

My mind leaps to images of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast. Of the bewitched Cogsworth and Lumière and the Wardrobe thundering about the Beast’s castle.

It wasn’t a tremble or a shake, but a walk, Bob stresses. Across the room.

As if possessed.

“And you both saw this?” I ask.

They nod.

“And you’re both sure?”

They nod again.

“So many things came out of that board,” Bob says, shaking his head. “So many things ...”

In the summer of 1968 or 1969, Bob, Roger, and three of their friends traveled to rural Alma Center, Wisconsin, to visit another friend, Louise. They were all in their mid-20s, newly minted-actors and journalists and teachers.

“We were there to watch a marzipan demonstration by Louise’s mother,” Bob recalls, “and to spend the day frolicking on the family farm.”

But come nightfall, all frolicking came to a halt.

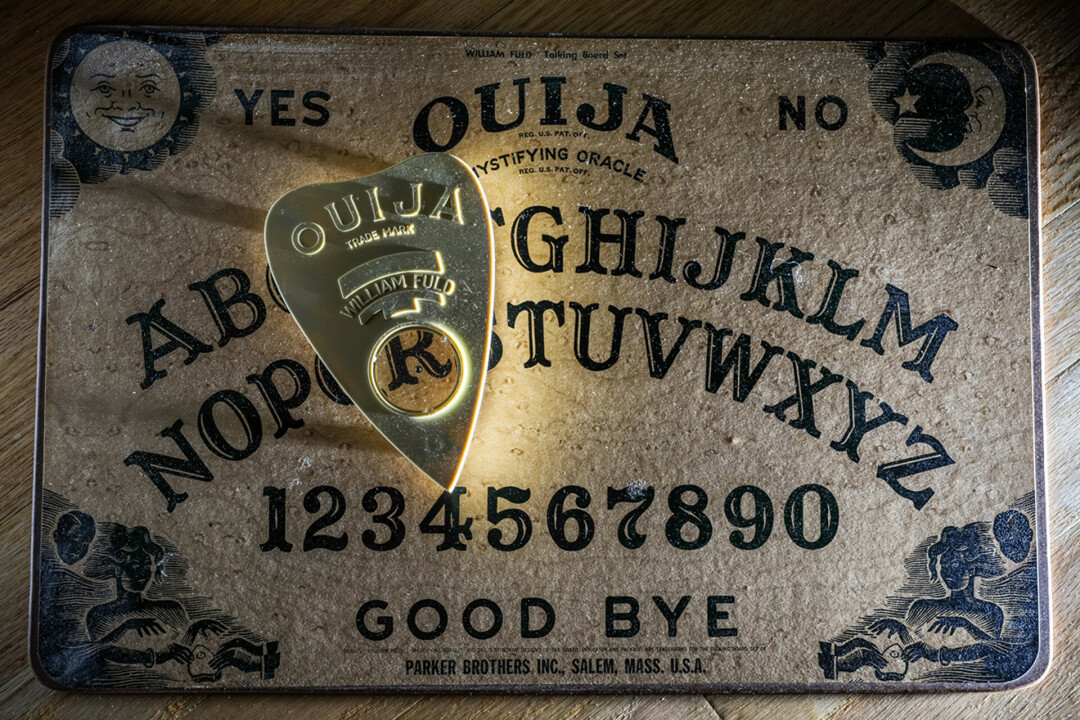

After an hour or so dedicated to telling ghost stories, they shifted their attention to the Ouija board that Bob and Roger had brought with them. Board in tow, the six friends started up the farmhouse stairs, soon arriving at a small room near the attic. They settled into position; fingertips placed lightly on the planchette.

It was, of course, a dark and stormy night. And it wasn’t long before a spirit arrived. When the friends’ asked for the spirit’s name, the planchette began skittering across the board’s letters, spelling the name of a woman none of them had ever heard of before. Puzzled, the six friends awaited further information.

Who was this spirit? What did she want? And why was she controlling the board?

The planchette continued its skittering, offering two additional words:

Everyone turned to Louise.

Do you have a family Bible? they asked.

Louise knew the family had a Bible somewhere, but by no means was it the kind of passed-through-the-generations “family Bible” she imagined the board might be speaking of. Just to be certain, Louise crept down the hall and woke her mother.

Do we have one? she asked.

Half-asleep, Louise’s mother confirmed that they did not, but that the farmhouse’s previous owners had left one behind.

In the attic, her mother whispered.

Louise started up the stairs, and upon reaching the top, rummaged through boxes and trunks as lightning lit up the sky. Thunder crashed in the distance, providing the perfect soundtrack to an ambience already a little too good to be true. The wind whipped around the corners of the farmhouse as the crops held firm in the mud.

At last, she came upon it – a Bible so thick it would’ve caused any bookshelf to sag. Leather bound, no doubt, with brittle pages.

Louise brought the Bible to the nearby Ouija room, and the others gasped.

How had the board known?

The six friends hovered over the long-forgotten Bible, and with the same lightness they applied to the planchette, they began to turn its pages. They’d barely cracked it before coming across a list of names scrawled inside the Bible’s flap – the lineage of a family, some of whom once called that farmhouse home.

There, among the names, was one they recognized: the woman’s name, which the board had spelled out just minutes before.

More lightning, more thunder, more silence.

“That’s when we ended the session,” Bob says.

There is an earthly answer for why the planchette moves. Scientists attribute it to the ideomotor effect, a psychological phenomenon in which a reflexive action occurs as a result of a thought. Unconsciously, our body works without our knowing it, moving the planchette, or the dowsing rod, or our hand during a session of automatic writing. Our unconscious leads us toward an answer whether we ask it to or not.

“That we can make movements that we don’t realise we’re making,” writes journalist Tom Stafford, “suggests that we shouldn’t be so confident in our judgements about what movements we think are ours.” Who, I wonder, is in control here?

That we can make movements that we don't realize we're making suggests that we shouldn't be so confident in our judgements about what movements we think are ours.

Tom Stafford

Journalist

The answer, of course, depends on who you ask.

What we do know is that throughout uncertain moments in history, we’ve often turned our attention to Ouija. Over a five months span in 1944 – as 73,000 U.S. soldiers trained for the D-Day invasion – back on the home front, a single New York department store sold 50,000 Ouija boards. Throughout the turbulent late 1960s, Ouija boards once more reigned supreme, outselling Monopoly.

Amid these uncertain times, people wanted answers they could trust. Or at least answers they could get.

Who – or what – could say what the future held?

In our current moment of uncertainty, will we dust off our Ouija boards yet again?

Gather round tables, press our fingers to planchettes, and wait, once more, for answers?

At my bravest, I remove the board from the box and imagine that dark and stormy night half a century ago when the spirit of a woman asked for her family Bible. And the night not long after when a coffee table marched across a living room floor.

Am I curious what that board might reveal to me if I dared ask it a question?

I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t. And yet, I don’t ask. Not ever.

In due time, the future always reveals itself.

You don’t need a board or a planchette to tell you that.

–

Portions of this piece were previously published in War, Literature & the Arts.

B.J. Hollars is a father, a writer, and a professor of English at UW-Eau Claire. His most recent book is Midwestern Strange: Hunting Monsters, Martians, and the Weird in Flyover Country, which was published in 2019 by the University of Nebraska Press.