Shortly after 6:30am on March 17, 1960, Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy — vying to win Wisconsin’s Democratic primary just two and a half weeks later — slipped from his plane at an Eau Claire landing strip and into a car headed 40 miles north to Cornell (population: 1,685).

It was day two of a five-day blitz across the state’s 10 congressional districts — a tire-burning barnstorm in which Kennedy would attempt to speak at every café, Elks Club, and high school that would have him.

Not that all of them were forthcoming in their invitations.

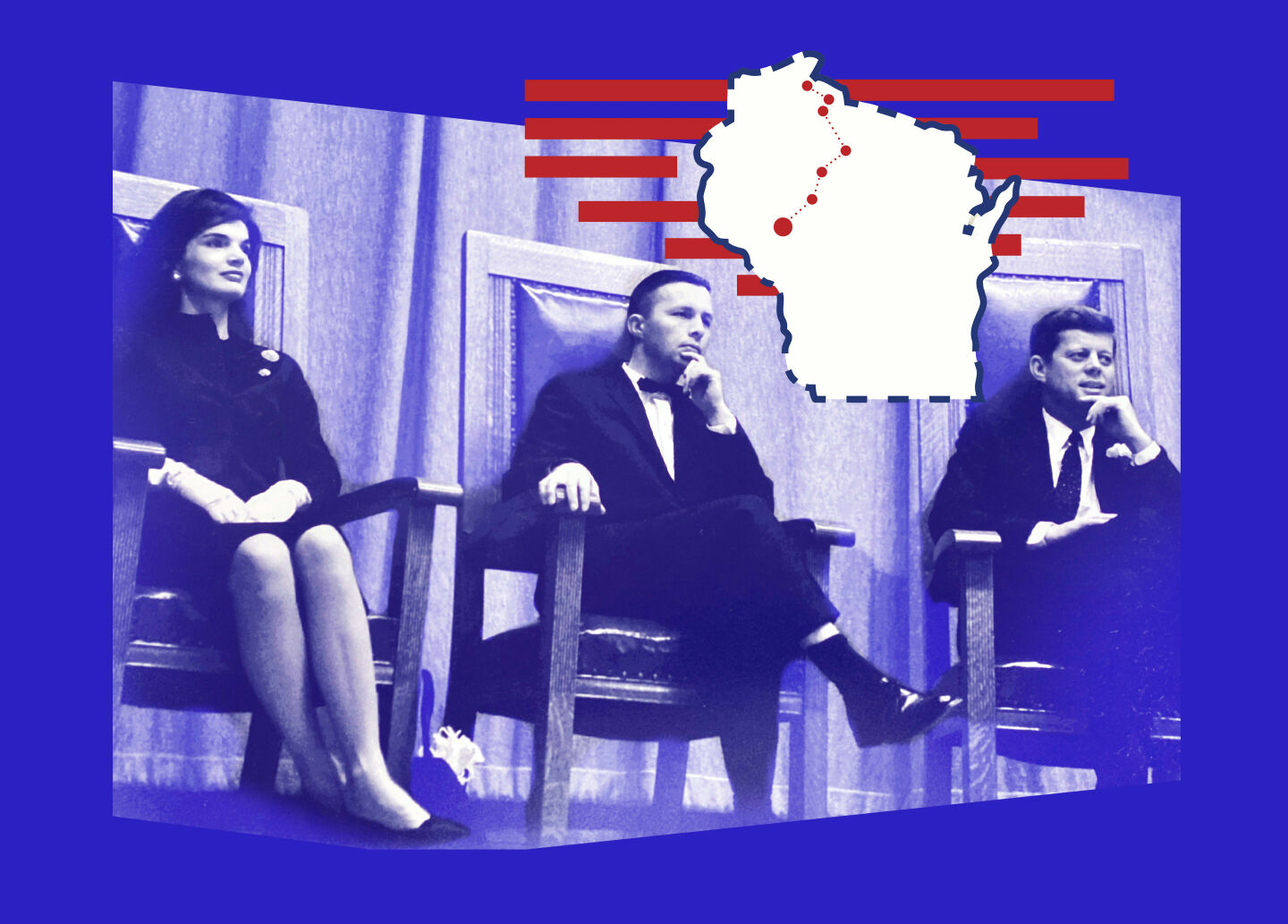

Time spent by Kennedy (shown here at Stout State College in Menomonie) in northwest Wisconsin would prove to be largely futile, as Dugal remembers: “It didn’t really turn out ... but we gave Hubert (Humphrey) a pretty good run in his home bailiwick.”

Hubert Humphrey, the farmer-friendly U.S. senator from Minnesota, had dedicated much of his political career to forging lasting relationships throughout the region. For Wisconsinites — particularly farmers in the northwestern part of the state — they much preferred the man they knew to the one they didn’t.

Which was precisely why Kennedy wanted his driver, 31-year-old Pete Dugal from the village of Cadott (population: 262), to pick up the pace. Pete, who just weeks before had joined five other Wisconsin delegates in endorsing Kennedy’s Wisconsin primary run for president, pressed down hard on the accelerator. Having spent World War II moving ammunition in the Army Transportation Corps, Pete knew a thing or two about the importance of timely deliveries. Only now, his cargo was more precious than ammunition: He had a potential future president alongside him.

With Dugal guiding the ship, Kennedy swept through Cornell, Ladysmith, Ingram, Prentice, Phillips, Montreal, Hurley, and Ashland in northern Wisconsin, meeting everyone he could.

Though the day had just begun, they were already behind schedule. Pete sped along the quiet roads, eventually bringing the car to a halt before Cornell’s N-Joy Restaurant, a roadside diner mostly indistinguishable from the others Kennedy had been frequenting for months. The senator leapt from the car, entering to find that eight people had gathered to greet him.

If Kennedy was perturbed by the small turnout, he knew better than to show it. Instead, he graciously reached for an elderly woman’s hand and gave it a shake. He flashed a smile, posed for a photo, and — for the sake of his own political survival — made himself available to every last one of them.

Though internal polling confirmed that Humphrey was poised to wipe the floor with Kennedy in Wisconsin’s northwestern districts, the senator refused to concede any ground. Instead, he entered directly into Humphrey’s territory, siphoning off votes wherever — and however — he could.

Though internal polling confirmed that Humphrey was poised to wipe the floor with Kennedy in Wisconsin’s northwestern districts, the senator refused to concede any ground.

Following their brief stop in Cornell, Pete and Kennedy continued 20 miles north toward Ladysmith (population: 3,584). A few campaign cars, as well as the press — both of which contributed to Pete’s desire to stick to the schedule, accompanied them. But Kennedy had other plans.

Peering out the window, the senator noticed several nuns in full habit awaiting him alongside the road.

“Stop the car,” Kennedy ordered.

No sooner had Pete pulled to the side of the road than Kennedy exited the car to greet them, even indulging the sisters by visiting their nearby convent.

While waiting for Kennedy to wrap up his glad-handing, an exasperated campaign advisor from another car walked up to Pete and asked, “Why the hell did you stop?”

“Gee, he told me to,” Pete said, “and I couldn’t very well go against him.”

“That’ll be the only press we’re going to get out of this trip,” the advisor said as the photographers swarmed. “They’ll sure as heck have pictures of it.”

The advisor was right.

Two weeks later, a photograph of Kennedy and the nuns of Ladysmith received half a page in LIFE magazine.

At the time, not even Kennedy’s political operatives could fully agree on the political calculus at play. Would a photograph of Kennedy surrounded by nuns reinforce the “puppet-to-the-pope” image, or merely add to the candidate’s appeal?

The question of religion would hound the Kennedy campaign long beyond the Wisconsin primary. While Kennedy had little problem denouncing papal interference in American politics, he was far more reluctant to hide from his faith.

Weeks prior, he’d encountered a similarly fraught situation during a campaign stop in Bloomer. The town’s funeral director had asked Kennedy to dedicate a new flag at St. Paul’s Catholic school just up the road from the café where the senator had been speaking.

Always mindful of the schedule, Pete tried to intervene.

“Gee,” Pete tried, “we’re way behind schedule.”

“Yes, let’s go over,” Kennedy said. “It won’t take long.”

Kennedy — accompanied by Jackie, complete in a stylish red overcoat and blue leather gloves — stationed himself alongside the flagpole as 150 Catholic students watched on.

Kennedy raised the flag, and the cameras zoomed in close.

“Well, that will take care of the press release,” one of the advisors grumbled, frustrated that the senator’s religion had again overshadowed the campaign.

“If I can’t go into a school here in this country and raise an American flag, even if it is a Catholic [school] … They aren’t going to vote for me anyhow,” Pete recalls Kennedy replying.

Whether because of Kennedy’s religion, his politics, or their loyalty to Humphrey, voters in the region’s Ninth District wouldn’t vote for him. Six weeks later, they’d cast their ballots in strong support of Humphrey — by a margin of some 10,000 votes.

* * *

Long before his time with the Kennedy campaign, Pete Dugal had served in the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force. He was a man who knew how to overcome obstacles, though few had seemed as daunting as helping Kennedy win Wisconsin.

In the two months leading up to the April 5 primary, Kennedy could regularly be found crisscrossing the state, often riding shotgun alongside Pete.

“I imagine, all told, Jack rode with me maybe a thousand, two thousand miles up and down the upper part of the state because he did spend a lot of time there,” Pete recounted in a 1966 interview. “It was mainly because he thought he had a chance of winning, where he was fairly sure of having the south [of Wisconsin]. It didn’t really turn out that way but we gave Hubert a pretty good run in his home bailiwick.”

In all those miles, Pete became far more than a Kennedy delegate and driver. He became someone the senator would come to rely upon, a man on the ground he could trust.

On January 20, 1961, Pete reversed the nature of their relationship by traveling to the president’s home turf, instead. Shivering outside the Capitol alongside a million others, he watched proudly as John F. Kennedy took the oath of office.

Yet 10 months prior, during Pete and Kennedy’s March 17 tour through northwest Wisconsin, nothing could have seemed less likely.

By noon that day, Kennedy had met with a grand total of eight people in Cornell, a handful of nuns in Ladysmith, and an unknown number of others en route to the village of Phillips (population: 1,524).

Upon arriving in Phillips, Pete parked the car and Kennedy took to the streets.

Only to find no one.

Presidential journalist Theodore H. White perfectly captured Kennedy on this less-than-fateful day, describing in detail the “forlorn and lonesome young man” who was “wandering solitary as a stick through the empty streets of the villages of Wisconsin’s far-north Tenth Congressional District.”

Finding the streets empty, Kennedy tried the hardboard factory where workers, according to White “grunted and let him pass.” He had even less luck at the local paper, “which was totally indifferent to the fact that a Presidential candidate” had paid them a visit, White continued. Next, Kennedy tried the cafés, where an equally cold reception awaited him.

“He left the town shortly after noon,” White continued, “and the town was as careless of his presence as of a cold wind passing through.”

Pete held the car door wide for the senator, and together, the men continued north toward the mining town of Montreal (population: 1,361). They stopped at a mine at the end of a shift, just as the miners were showering and changing into clean clothes.

It made for an awkward situation, Pete remembered.

“We were trying to pin buttons on these people and half of them were running around there naked so that was a kind of a problem.”

To the surprise of everyone, Kennedy’s fortunes changed in the nearby city of Hurley (population: 2,763). Pete glanced toward the senator to catch his eyes widening as a crowd nearly 800 strong packed the small town’s streets. In his eagerness to speak to supporters, Kennedy inadvertently stuck himself in the hindquarters with a campaign pin. He let loose a string of curse words, then found his smile just in time to greet the crowd.

“He seemed to be well received;” Pete remembered, “you’d call it an enthusiastic crowd.”

Some of that enthusiasm may have come courtesy of the miners, who, at the end of their shift, had gained a reputation for reserving their more debaucherous behavior for Hurley, a city never in short supply of bars or strip clubs. One way or another, Kennedy became privy to Hurley’s reputation.

“Are there really a lot of whores in this town?” Kennedy asked as they left Hurley in the rearview.

“That’s what they say,” Pete said, speeding the senator out of town.

* * *

By day’s end, Pete had added some 200 miles to the odometer, transporting Kennedy from Eau Claire to Cornell to Ladysmith to Ingram to Prentice to Phillips to Montreal to Hurley and finally, onto Ashland (population: 10,132). The day ended mostly without incident, with the exception of a run-in with an Ashland hotel owner who, in her zeal to accommodate the senator’s known back problems, had acquired a board for him to sleep on. Upon learning that Pete and another advisor were actually her lodgers — and that Kennedy was staying with a competitor up the road — the owner, perhaps a bit heartbroken, stiffly sent them packing.

It was a fitting end to a long day. One filled with high points, but disappointments, too.

Theodore H. White estimated that by day’s end, Kennedy had “seen no more than 1,600 people, of whom probably 1,200 were children too young to vote.” While there was something admirable about Kennedy’s doggedness, White remarked that the senator’s failed effort to win the hearts and minds of rural Wisconsinites seemed only to reinforce the preposterousness of his run for president. “Except,” White added, “that it did not seem preposterous to Kennedy himself.”

While Hubert Humphrey relied on longstanding loyalties to pay off at the ballot box, Kennedy — the Catholic, East Coast elite — had to rely on a charm offensive, instead. And many western Wisconsin’s farmers weren’t buying it.

Which left Kennedy and his advisors with a difficult question: How was he to ingratiate himself to a constituency he simply did not know?

This was never clearer than on a cold February morning in 1960, when a farmer from Bloomer called Kennedy out during a campaign visit in a café. The farmer explained that he and his friends were all Humphrey men because Hubert Humphrey understood what it meant to be a farmer, and Kennedy didn’t.

“As a matter of fact,” the farmer continued, adjusting his bib overalls, “we don’t even think you know what a farmer is.”

I imagine the sweat forming atop Pete’s brow as he waited to see how the Princeton- and Harvard-educated politician would respond to the Wisconsin farmer. Campaigns were won and lost in moments such as these, Pete knew. Moments, seemingly small, that had the power to define a politician forever.

Sen. Kennedy paused, searching for an answer, and found one.

“Well, it’s true that Sen. Humphrey has done a lot for the farmers and worked hard for them, and it’s easy for you to criticize me because of coming from the East Coast,” Kennedy conceded. “But, I’m a little disappointed that you would accuse me of not knowing what a farmer is,” he said, preparing for the punch line. “A farmer is a man ‘outstanding’ in his field.”

Laughter shattered the silence.

Kennedy’s witty retort may have won him a few voters, though not nearly enough. On the other hand, Humphrey had his own problems to contend with. At every turn, he was out-staffed, out-spent, and out-hustled. As White reported, Humphrey’s weekend staffers and bus were no match for Kennedy’s full-time team and private plane. At one point in the campaign, Humphrey noted that it was like “a corner grocer running against a chain store.”

On the evening of April 5, Kennedy and his team holed up in Milwaukee’s Pfister Hotel, anxiously awaited the primary returns. Less than a mile away, at the Knickerbocker Hotel, Humphrey and his team did the same. Two hours after the polls closed, the results were clear: Kennedy had squeaked out a victory, paving the way for an uphill battle in the West Virginia primary just a month away.

It was a solid showing, though hardly a decisive victory. The western districts were to blame, which included many of the cities and towns and villages Pete and Kennedy had visited on March 17, 1960.

Despite Pete’s best efforts, the headwinds against Kennedy were simply too strong in the west. That part of the state was Humphrey country, Protestant country, and farm country, too — a one, two, three punch that the East Coast, Catholic politician could barely weather. But weather it he did. And by some measures, he even thrived.

Over the span of two months, Kennedy had transformed from the “forlorn and lonesome young man” Theodore H. White had witnessed roaming the Tenth District, to the man who would receive 28,000 votes there, only 4,000 fewer than Humphrey.

Winning the Wisconsin primary was about more than delegates. It was about bolstering Kennedy’s electability on a national scale. What still remained to be seen was if Kennedy could persuade West Virginia’s Protestants to vote for him in the upcoming primary. If, despite his appearances with the nuns in Ladysmith and at the flag dedication at St. Paul’s in Bloomer, West Virginians were still willing to give him a chance.

They were. And in doing so, followed Wisconsin’s lead in helping Kennedy secure the Democratic nomination for president.

* * *

Pete Dugal passed away in 2017 at the age of 88, spending his final years in Fort Collins, Colorado, alongside his wife and their son, Dan; the latter of whom is a 1996 graduate of UW-Eau Claire.

During Dan’s time at UWEC, he regularly roamed Davies Student Center, but it wasn’t until Davies was slated for demolition in 2011 that Dan learned of the photograph of his father that had, apparently, been hanging in the building for years. The photo features his bow-tied father seated in a thronelike chair with Senator Kennedy and Jackie Kennedy on either side of him. Though undated, it was likely snapped at the Eau Claire Elks Club on Feb. 26, 1960 — the same day Kennedy managed his witty retort about the farmer being “outstanding in his field.”

Seated between Jackie and John F. Kennedy during a campaign visit to Eau Claire in 1960 is Pete Dougal, a Chippewa Valley native and Kennedy’s personal driver, who took the then-candidate all over the state to energize his presidential campaign in Wisconsin.

The photo is stunning for a number of reasons, not least of all for its focal point. How many times in American history had the limelight gone to a delegate from Cadott rather than the Kennedys?

Dan was astonished to see the photo, and equally surprised by what it said about his father. Though Dan and his siblings were aware of the generalities involving his father’s role in the Kennedy campaign, they’d never quite known the extent of his work.

The photograph changed that.

“We were like, ‘Oh my gosh, [Dad] really did do a lot of things with him,” Dan tells me in a recent interview.

Let the record show that I am no Pete Dugal. Yet for much of the fall, I’ve been doing my own small part for democracy. This mostly involves me picking up the phone and encouraging people in our district to vote. Often, I am not well received. Often, I’m greeted by dial tone or worse.

Still, I keep calling. Because democracy is won not only by those who show up, but by those who do the work prior to it.

Of course, history has a short memory for such people. But it’s people like Pete — who possess an indefatigable commitment to their candidates — that reenergizes our democracy far better than any bumper sticker or button. Though they never make stump speeches, accept nominations, and only rarely find themselves in the center of photographs, they nonetheless possess the power to change history.

What might’ve become of John F. Kennedy had Pete Dugal not played such an active role in Wisconsin? While it’s wholly unlikely the scales of power would’ve tipped toward Humphrey, had a dozen Pete Dugals decided to sit out the primary, the alternative history becomes clearer.

Were it not for Pete’s foot on the accelerator, day after day, might the Cuban Missile Crisis have ended differently? Might Americans have never made it to the moon?

If Kennedy had lost Wisconsin, how might the bruised senator have fared in West Virginia? And if he’d lost there, too, might Humphrey have won the nomination? And might he have lost to Nixon in the general?

Were it not for Pete’s foot on the accelerator, day after day, might the Cuban Missile Crisis have ended differently? Might Americans have never made it to the moon? And, in a strange twist of fate, might a grandfatherly Kennedy be seated in a rocking chair this moment, regaling his grandchild about the time he almost won the Democratic nomination for president?

Such hare-brained hypotheticals are without answer. But what we do know, we have always known: that the fate of our democracy depends on people like Pete Dugal — people who take Kennedy’s inaugural address advice to heart, asking not what their country can do for them, but what they can do for their country.

In 1960, Pete Dugal knew just what to do.

He took his seat, buckled up, and drove his country forward.

B.J. Hollars is a father, a writer, and a professor of English at UW-Eau Claire. His most recent book is Midwestern Strange: Hunting Monsters, Martians, and the Weird in Flyover Country, which was published in 2019 by the University of Nebraska Press.