Wisconsin’s Been Here Before: Let’s Learn From Our Past, Then Repeat It

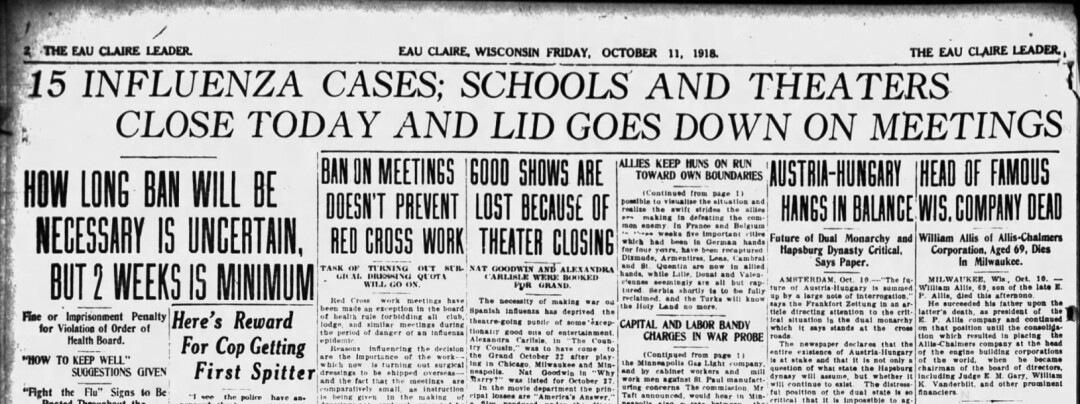

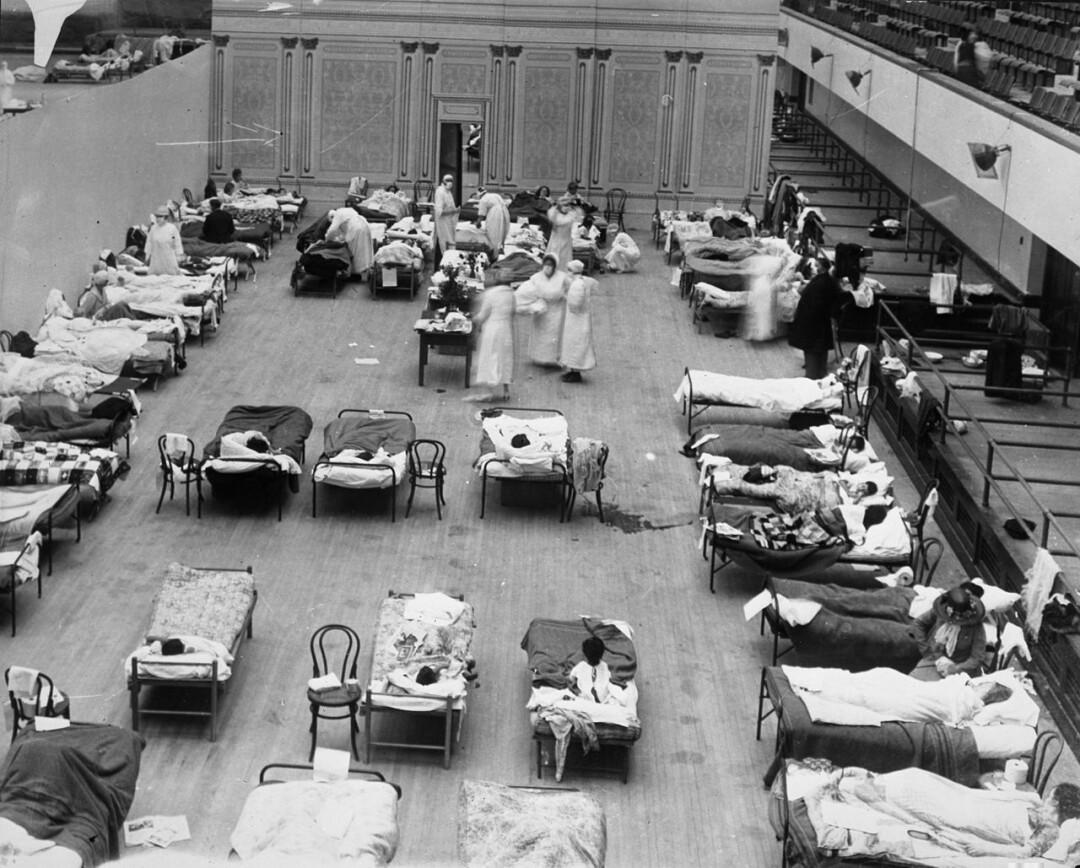

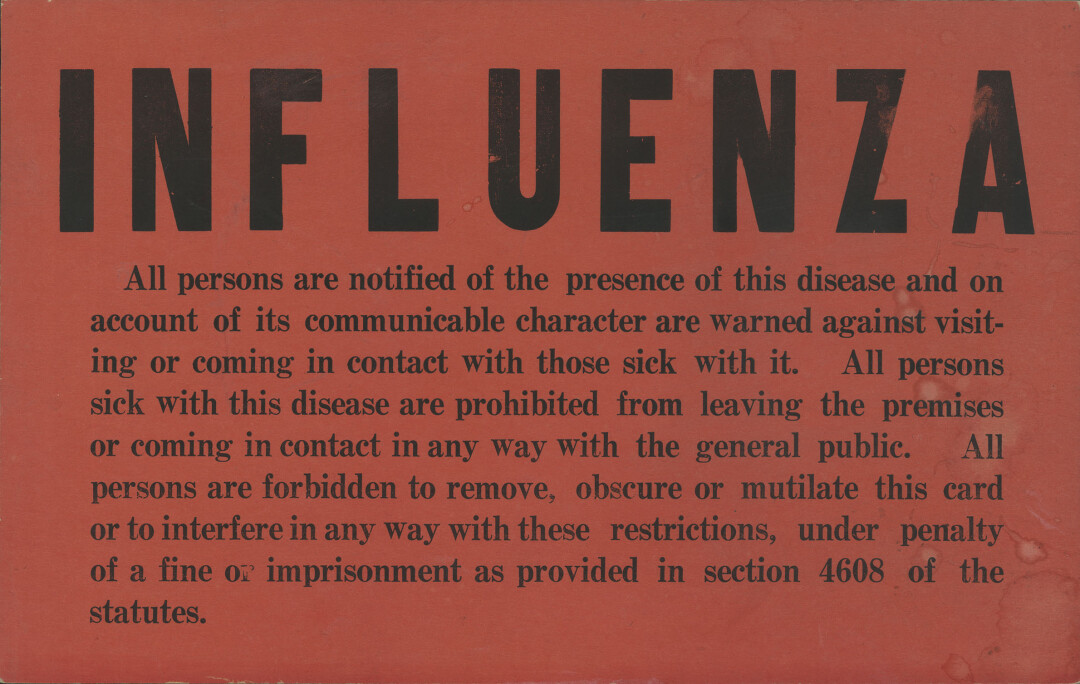

On October 11, 1918, Eau Claire citizens reached for their local newspaper to learn that their world had dramatically changed. Displayed prominently was an order from the local office of the Board of Health, which stated that for the foreseeable future, the city prohibited “all public meeting and gatherings of all descriptions.” This included schools, universities, churches, lodges, dances, theaters, picture shows, and the public library. Though these measures may have seemed extreme for the city of 20,000, in fact, they were on par with similar directives to be implemented throughout the country. Over the previous two weeks, the swiftly spreading Spanish influenza had wreaked havoc across the nation. By month’s end, it would claim the lives of more than 195,000 Americans – a death toll over 40% higher than all U.S. casualties throughout World War I, which was raging at the same time. After years of trench warfare half the world away, Americans were shocked to learn that a far deadlier battle was being waged in their own backyard. No longer would victory and defeat be determined by the country’s armed forces. Now, it was up to every American to fight.

“Prevention of the spread of this disease in this community depends absolutely upon the loyal and intelligent effort of every citizen,” Eau Claire’s Board of Health explained, adding also that the board “anxiously awaits your cordial support.”

And then a miracle occurred: The people of Eau Claire listened.

And even more astonishing: So did most folks statewide.

The state’s swift and decisive action soon served as a model for the country. “Wisconsin was the only state in the nation to meet the crisis with uniform statewide measures that were unusual both for their aggressiveness and the public’s willingness to comply with them,” writes historian Steven Burg. As a result, Wisconsin’s citizens endured the pandemic with a death rate far lower than the national average.

So what did Wisconsin do right?

First, state leaders enacted policies to ensure that their citizens’ health remained at the forefront. Though mindful of the economic, cultural, and political toll of shuttering schools and businesses, state leaders remained confident that doing so was the best course of action. “Inconvenience or monetary loss must result to a good many as a result of the order,” confirmed one Eau Claire doctor. He was right. But that knowledge didn’t deter the decision.

Second, citizens trusted their local, state, and federal government to lead them. Admittedly, it’s hard to imagine such trust given today’s polarizing political climate. But a century ago, Americans were nearing their third decade of the Progressive Era. They had long witnessed government’s ability to successfully solve problems as wide-ranging as industrialization and political corruption. And so, when leaders told citizens to stay indoors, the citizens listened.

In retrospect, it seems a simple formula for success: Elect leaders you trust and then trust them to lead. But these days, trust is in short supply. Recent Gallup polling reveals an erosion of confidence in our institutions, with over half of Americans expressing “very little” or “no” trust in Congress, and only slightly higher numbers for the presidency. We can debate the reasons for this erosion, but the result is beyond dispute: When we don’t trust, we don’t listen. And in this instance, not listening could have a dramatic and deadly effect.

In 1918, we trusted more, we listened better, and likely thousands of Wisconsinites were spared. In total, 8,500 of our state’s residents died – just over 1.2% of the estimated 675,000 Spanish flu-related American deaths. In Eau Claire County, 52 people died. While the loss of every citizen was surely felt, those who survived recognized how quickly that number might have skyrocketed had leaders and citizens responded differently.

Not only did Wisconsinites come together in common cause, but they excelled at it. For many, this meant isolating themselves in their homes for three months, a sacrifice they were willing to make to ensure the safety of their wider communities.

Writing in 2000, Steven Burg remarked, “In an age of apathy, cynicism, and individualism, it is worth reflecting long and hard that volunteerism, public cooperation, and an activist government prevented the worst public health calamity in modern Wisconsin history from being much, much worse.”

Are we still capable of looking beyond ourselves to limit long-term damage?

Or to put it more bluntly: Are we capable of living our lives as if all of our lives depend upon it?

Because now, all of our lives most certainly do.

That our personal health is directly linked to our collective action is, indeed, terrifying.

But here’s the good news: We Wisconsinites made the right choice before, and I believe we can do it again.

Please, be like our predecessors: Hole up, hunker down.

Let’s wave to each other from our windows.

B.J. Hollars is a father, a writer, and a professor of English at UW-Eau Claire.