For more than 30 years, Tokyo Restaurant has brought international cuisine – and understanding – to the Chippewa Valley

words by Emily Anderson design by Eric Christenson

photos by Andrea Paulseth

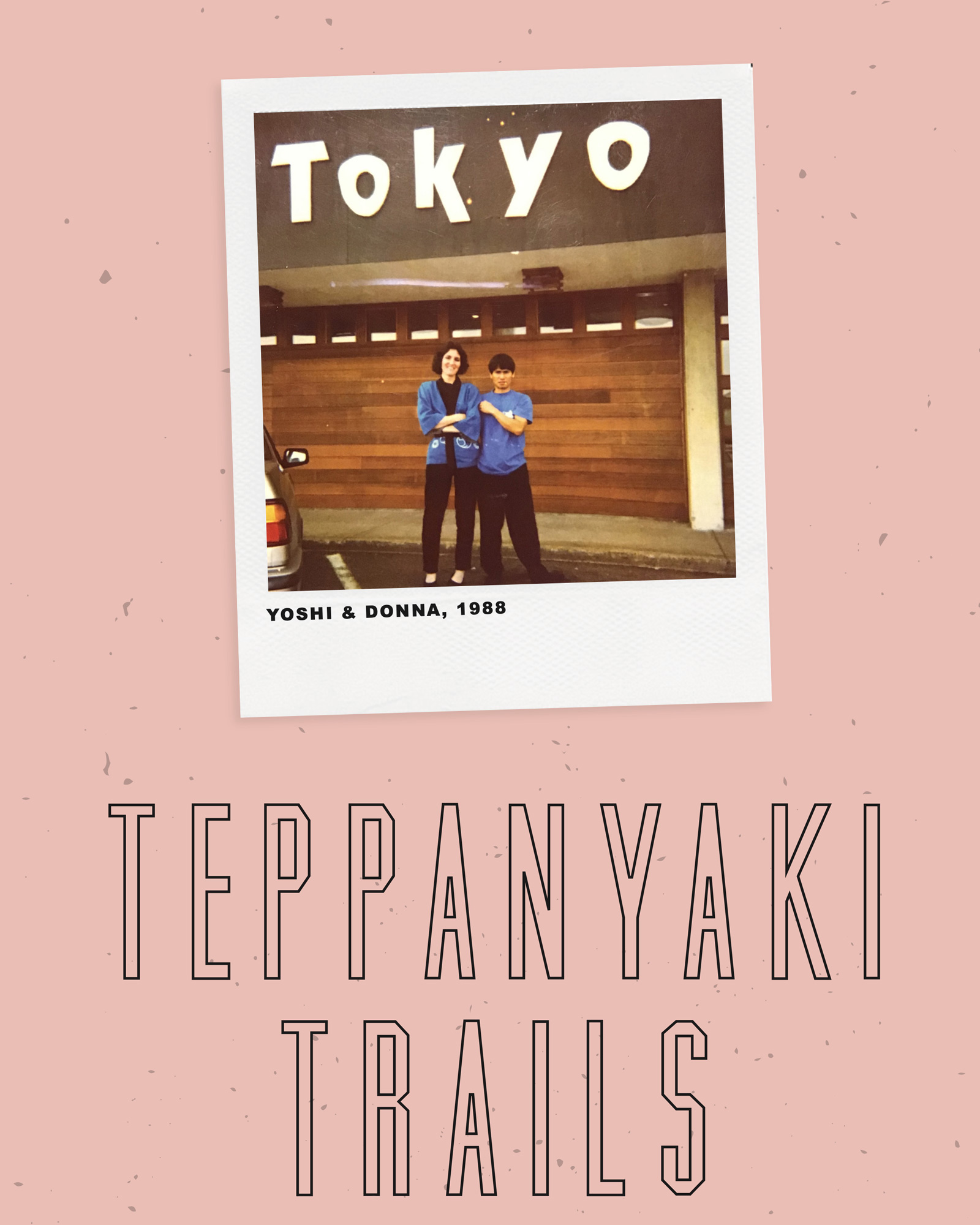

YOSHI & DONNA, 2020

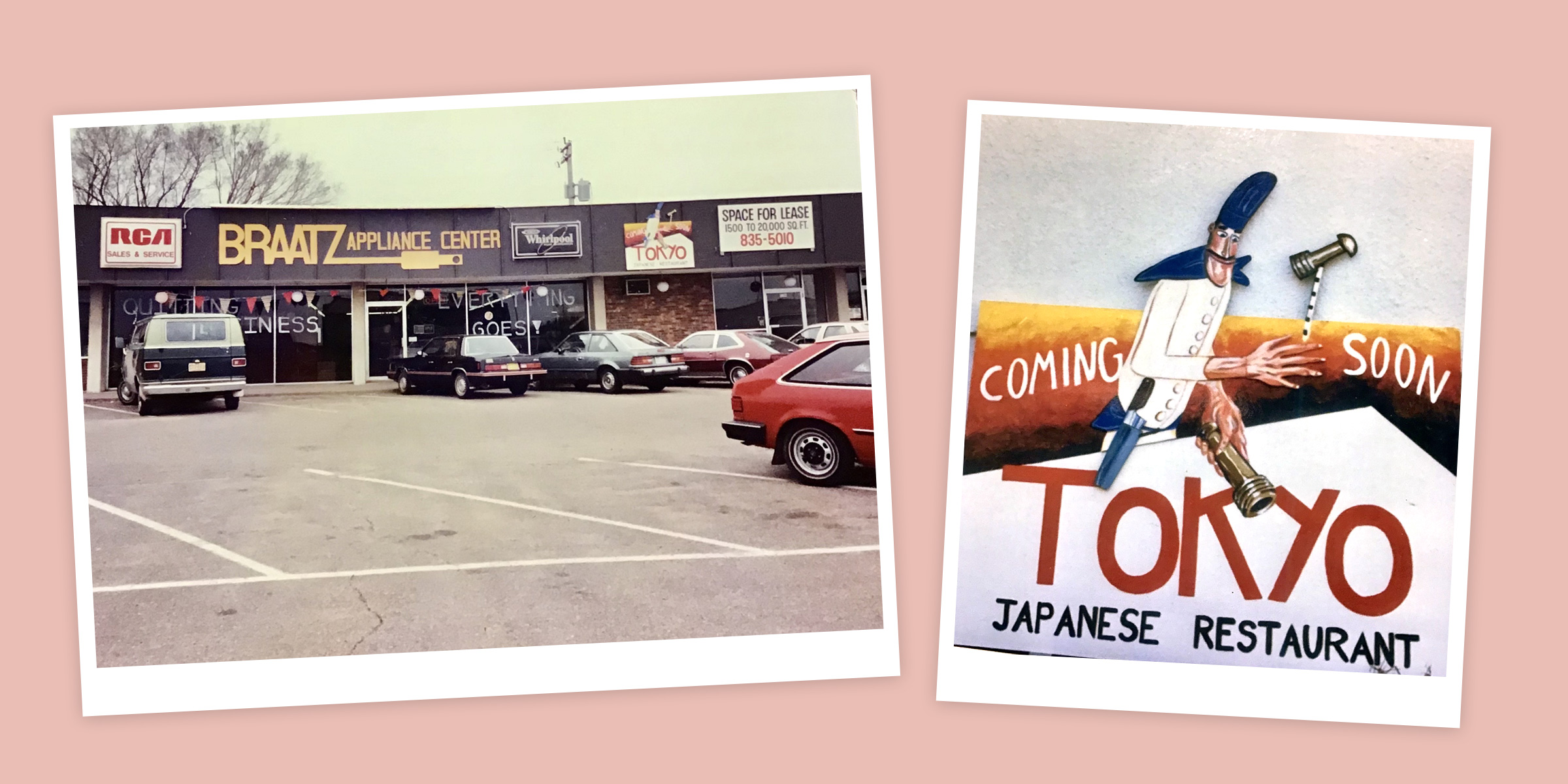

Tokyo Restaurant has been located in a modest strip mall on London Road since first opening in 1989. Still, you could say the history of the restaurant truly began in 1969. That’s when the restaurant’s founder, Yoshi Tsuanko, left Japan and came to the U.S.

At that time, Yoshi was a new high school graduate. He wanted to see the world. So he tossed a Japanese-English dictionary in his backpack, boarded a ship bound for Argentina, got off at Long Beach, California, and hitchhiked up and down the coast.

It was the year of Woodstock and the moon landing. People were hitchhiking all along the scenic Pacific Coast Highway. Teenage Yoshi was among them. He pinned a giant Japanese flag to his backpack and stuck out his thumb. Sometimes Japanese drivers pulled over and gave him rides. Other times he walked. He went to San Francisco and slept on the beach at Monterrey.

Yoshi’s adventurous spirit took him on a winding path that ultimately led to Wisconsin.

In the 1980s, Wisconsinites were less familiar with different cuisines and cultures than they are today. (For example: in the ’80, my parents were part of an international cooking club. Recently, I found the club’s recipes. Beneath one recipe, someone had thoughtfully spelled out the phonetic pronunciation for the word tacos: “tah-kos.” Alongside the recipe for guacamole, I saw a note in my dad’s handwriting. It said, a kind of dip.) For the past 31 years, Tokyo Restaurant has expanded the palates – and minds – of Eau Claireans.

The restaurant was recently sold, and as it transitions into its next phase, I want to tell the story of Tokyo Restaurant and reflect on what it’s meant for me, and for our community, to enjoy Japanese teppanyaki (cook-at-the-table) dining from the age of “tah-kos” to today.

Tokyo Restaurant was where I, as a 10 year old, first managed to eat with chopsticks. (The waitstaff rubber-banded them to make them easy to use.) I watched chefs wield wild knives over a sizzling grill as jets of steam puffed from stacked-onion “volcanos.” Just as astonishingly, strangers joined my family at the table. Should I make eye contact? Were we supposed to talk? The uncertainty thrilled me. Eating at Tokyo was an invitation to an adventure – and perhaps it felt that way because Yoshi, who founded the restaurant with his wife Donna, wound up in Eau Claire because he, too, loved adventure.

I had a chance to talk with Yoshi and Donna as part of a larger project sponsored by Eau Claire’s JONAH (Joining Our Neighbors Advancing Hope), which is collecting stories about the experiences of immigrants in Eau Claire with the sponsorship of the Mahmoud S Taman Foundation. Yoshi told me that he arrived in California with no job and no plan, but eventually found a job picking lettuce alongside workers from Mexico and Latin America. He made $1.65 an hour, and even though he was young and healthy, the work was so arduous he grew ill. He returned to Japan, where he enrolled in business school. But he yearned to come back to the U.S.

At that time, Benihana, the international chain of teppanyaki restaurants, was growing. Yoshi saw this as his chance to return to the U.S. He trained to be a chef at Benihana. When he left for New York City, his parents gathered at the dock to see him off. They threw ticker tape at his ship as it pulled out of the harbor.

Yoshi cooked for Benihana in New York, Chicago, and Newport Beach, California. He traveled across the U.S. whenever he could, often taking Greyhound buses. He never imagined that his destiny lay waiting for him in Eau Claire, but he may have had one hint: on one of Yoshi’s Greyhound trips, the bus pulled in to the depot in Eau Claire. Yoshi vividly recalls going down the Brackett Avenue hill. He didn’t know at the time that one day he’d return to Eau Claire and build a life – yet something about the city stood out to him.

While cooking in California, Yoshi was hired by Reiko Westin to work at Fuji Ya in Minneapolis. It was there that fate caught up with the adventuresome Yoshi: He met Donna, who worked in the kitchen. Yoshi and Donna fell in love at Fuji Ya, and they got married. They set off pursuing their dream of starting their own teppanyaki restaurant.

There were already a few Japanese restaurants in the Twin Cities, so they considered starting a restaurant in La Crosse. However, they learned that someone else had recently opened a Japanese restaurant there. So they turned to Eau Claire. In the 1980s, they told me, Eau Claire was the right-size city. At that time, there were no other Japanese restaurants. In fact, in 1988, there were just 60 restaurants, total, in Eau Claire. Today, they said, there are over 200 restaurants in Eau Claire. It’s no longer unusual to find international cuisine in our community; Tokyo, as well as many other immigrant-owned businesses, have played a part in Eau Claire’s transformation.

Food can be an opportunity for people to create connections and open their minds. In fact, the history of teppanyaki dining reflects the ways that people from different backgrounds can come together over a meal.

Yoshi loves America because it’s a country built by immigrants; it’s a place where people from all over the world come to live. Donna and Yoshi told me that part of their goal in owning Tokyo has been opening people’s minds to other cultures and the ways that they enrich the United States. Food can be an opportunity for people to create connections and open their minds. In fact, the history of teppanyaki dining reflects the ways that people from different backgrounds can come together over a meal.

Remember how I said that Tokyo Restaurant’s story truly started in 1969? It would also be fair to say that story really began right after World War II. Teppanyaki dining, the style of cook-at-the-table dining, doesn’t have a long history in Japan. It was started in 1945. After the close of World War II, American troops occupied Japan. An enterprising Japanese chef wanted to serve food that these homesick American troops would enjoy. So he tried to imitate American style cooking by grilling steaks on a flat iron grill called a teppan. That’s how teppanyaki got started. Teppanyaki dining carries a history of an unfathomably violent war — and also the miraculous promise of reconciliation through everyday acts of cooking and eating.

The Benihana restaurant chain, which brought teppanyaki dining from Japan to America (and which also brought Yoshi to America) has its roots in this same wartime history. After the war, a man called Yunosuke Aoki returned to his home city of Tokyo, which lay in ruins after Allied bombings. He saw a safflower (benihana in Japanese) sprouting from a crack in the rubble, and it gave him hope. He started a coffee shop because he wanted to create a place where people could come together and smile again. He called his cafe “Benihana.” Twenty years later, in 1964, his son, Hiroaki “Rocky” Aoki, started a restaurant in New York City and named it “Benihana.” It, too, would be a place where people could come together.

Aoki chose to feature teppanyaki-style dining at his New York restaurant because he thought that creating fun dining experiences would help Americans get over their fear of Japanese food (and, by extension, their prejudices against Japanese people). The first Benihana restaurant opened in the U.S. just 20 years after the Japanese internment camps had closed. Since then, Japanese restaurants have long played a role in helping diners overcome biases.

In Eau Claire, Yoshi and Donna gave diners a taste of the wider world and the opportunity to open their minds to a new culture. As a kid, Tokyo Restaurant was one of the few things I knew about Japan. Yet looking back on it, when I ate at Tokyo, I wasn’t really seeing a vision of Japan. I was seeing America in a new way – as a place of possibility, a hub for global connections. Like the restaurant they built, the story of Yoshi and Donna’s journey reminds us that, even if our cars are buried in snow, we’re not, actually, stuck: We can still enjoy the adventure of learning new things and getting to know people whose backgrounds differ from our own.

At the end of October, Yoshi and Donna set out on a new adventure: retirement. The restaurant has been sold, and the new owners – Charlee Markquart and Ryan Warffuel – will, in Donna’s words, “pick up where we left off” and “hopefully enjoy another 31 years in this community.” I’m looking forward to seeing the next phase of Tokyo Restaurant. When talking with Yoshi and Donna, what stands out most to me is Yoshi’s description of his free-spirited travels in California in 1969. “I didn’t have any fear to do anything or go anywhere. I was young,” he told me. Let’s hope that the renewed Tokyo Restaurant will continue to inspire Eau Claire diners to set out on their adventures with fearlessness and joy.

Learn more about Tokyo Japanese Restaurant on Facebook.

CHARLEE MARKQUART

It’s official: Tokyo’s new owners, Charlee Markquart and Ryan Warffuel, have added traditional Japanese ramen to Tokyo’s menu. Charlee is enthusiastic about serving the authentic, house-made noodles, but he assured me that other aspects of Tokyo won’t change. Charlee and Ryan have kept Tokyo’s entire staff and will continue to use Yoshi’s original recipes and ingredients. Charlee describes Tokyo as an “Eau Claire institution” that he hopes to continue; the addition of ramen will be the only change to the menu.

Just as Yoshi and Donna’s story has its roots in adventure, so to, too does Charlee and Ryan’s. The business partners have been close friends for many years – including during their time at South Middle School and Memorial High School. They had long sought an opportunity to go into business together, and planned to open a ramen shop similar to restaurants that have been successful in the Twin Cities. When they learned that one of their favorite restaurants was for sale, they seized on the opportunity to continue Tokyo’s legacy and expand it with the addition of the popular Japanese noodles.