the past, present, and future of Eau Claire’s towering timber

words by Eric Rasmussen, photos by Andrea Paulseth

Sometimes, we forget to look up. And other times, when we remember, we look up too far and get lost in the clouds. The sky holds other features worthy of our attention, higher than the horizon, lower than the stratosphere.

Trees.

Luke Cain, City of Eau Claire Forestry Division, trimming trees

Living in western Wisconsin means trees are a local feature we can all take for granted. There are tons of them, literally. New ones sprout and old ones are sent to the chipper every day. Like blades of grass in Carson Park or grains of sand on Lake Altoona Beach, our area features an uncountable number of red pines and maples and elms and all the others.

Except completing such a count is someone’s job, and the number is 32,815, as of a warm day in mid-August. When Matthew Staudenmaier, forestry division supervisor for the City of Eau Claire, looks up at a tree, he sees far more than leaves that will eventually need raking and branches that need pruning. On that August afternoon, he invited me on a tour of the city’s trees through the eyes of an urban arborist. (To clarify, Staudenmaier’s census and job responsibilities only cover the trees on all city-owned property, such as boulevards and parks.) I learned more about Eau Claire’s trees than I would have guessed there was to know, and buried amongst all that information were two important lessons: First, Staudenmaier and his dedication to the trees are, without a doubt, among Eau Claire’s greatest municipal assets. Second, you should be paying attention to our trees. Here’s why.

Matthew Staudenmaier, City of Eau Claire Forestry Division Supervisor

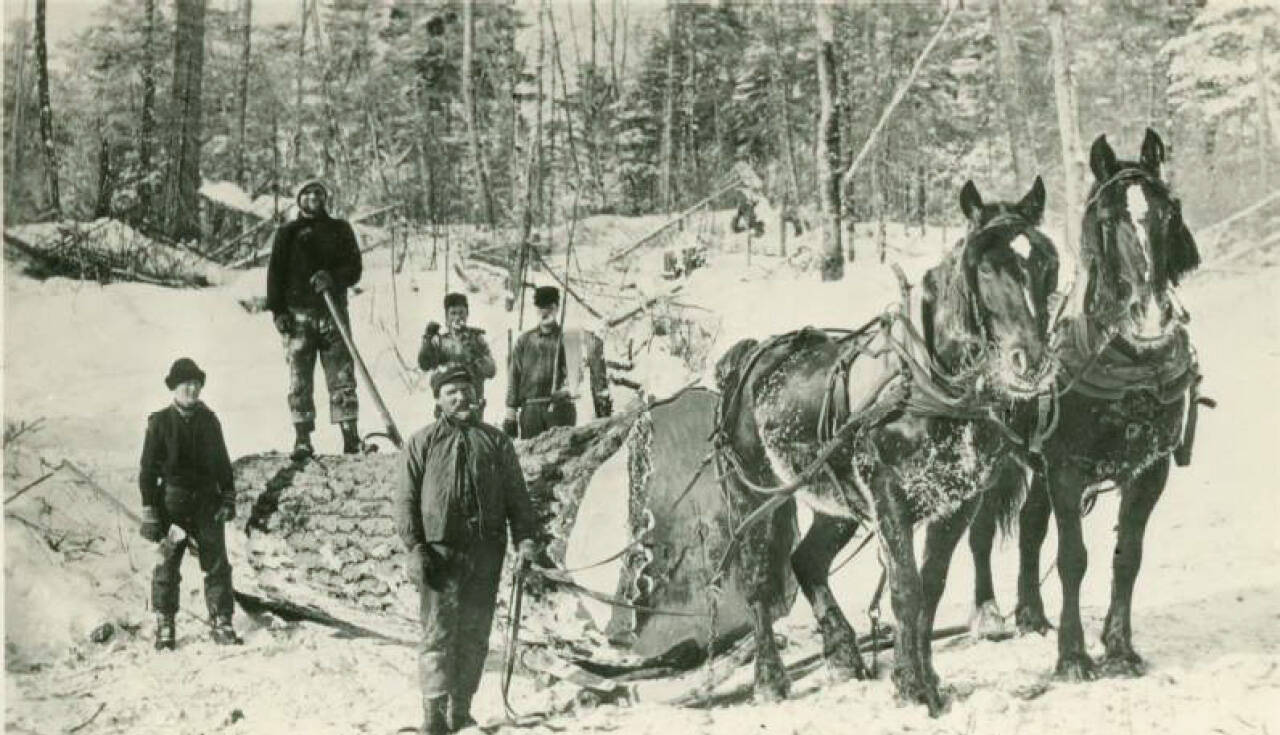

Crew decking logs onto horse-drawn sled. Photo courtesy of the Chippewa Valley Museum

Trees of Eau Claire’s Past

Prior to the settlement of the area by European immigrants, native peoples lived amongst towering, ancient white pines that blanketed much of the top half of the state. But after the newcomers wandered in and wondered at the majesty of the local forests, the economic allure of all that timber prompted them to cut everything down. They did a thorough job; almost no old-growth white pines remain in Wisconsin. Eau Claire’s location at the confluence of the Chippewa and Eau Claire rivers made it something of a logging hub. Felled trees floated down the waterways and became lumber in our sawmills, all while Eau Claire catered to the varied needs of the lumberjacks. When the trees ran out, we got a tire factory, then Oakwood Mall, then Phoenix Park. End of recap.

This history yields an interesting implication for our local tree population. The Chippewa Valley is home to very few old trees. As Matt and I drove around Eau Claire in his pickup, he pointed out the most massive and impressive specimens that line our streets and populate our parks. None of them are much more than a century old, however, thanks mostly to the logging frenzy. But 19th century industry is not solely to blame for the state of our trees. A little less than one hundred years later, nature itself joined the assault.

Five crew men skidding huge log with two horses. Photo courtesy of the Chippewa Valley Museum

“The storm of 1980 wiped out many of the city’s trees,” explained Staudenmaier. (Another quick historical recap: in June of 1980, a storm ripped through Eau Claire. It wasn’t a tornado, but it produced straight-line winds of 112 miles per hour, more than enough to topple or break off any trees of notable height.) The evidence of this storm is still present today. Just head to Owen Park and look up. “They’re called wolf limbs,” said Staudenmaier, pointing out the places where the trees put out curved limbs to bypass places where upper sections had broken off. “A lot of these trees would be much taller if it hadn’t been for that storm.”

But local tree history isn’t all pain and suffering. Eau Claire is designated as a Tree City by the National Arbor Day Foundation, and we’ve held that title, awarded based on per-capita forestry spending, for 40 years. “We’re tied for the second longest Tree City designation in the state, with Sheboygan,” said Staudenmaier. “Our community has a desire for the beauty and health that only trees can provide. Visitors to our city comment on the trees. We’ve got a culture around our trees, not to mention all they do for air quality, temperature control, and water management.” And thanks to Matt and his team of four certified arborists, the future of local forestry looks much leafier than the past.

Trees of Eau Claire’s Present

Despite not always seeing the local forest for the individual trees, many Chippewa Valley residents have a favorite giant elm or colorful maple or some species they may not be able to identify. When I asked Matt if he would show me some of his most notable local trees, I got the impression that I had asked him to choose a favorite child. During our tour we visited numerous different options, all of which I had seen before, and none of which I had ever noticed. The five that follow here are all accessible, unique, and definitely worth a visit.

American Burr Oak | Forest Street Park

Our first stop was just down from the city buildings that house the Forestry Division and other offices, as well as all the snowplows and city equipment. There we found an American Burr Oak, which is the type of tree often associated with the prairie, standing out alone in fields with limbs that grow outward, then upward. The one located along the Chippewa River, across from Forest Street, is a good one. According to Staudenmaier, “It’s at least 150 years old, maybe closer to 200.” This tree also serves as the final test for local arborists. If they can climb the complicated tangle of the Forest Street Burr Oak, they can handle anything. While we marveled at the tree, we were approached by a city engineer finalizing plans for the construction on Forest Street that was about to commence. Matt and his colleague discussed storm sewer lines while I watched. “We can stand to lose the rest of these trees. But not this one,” said Matt, pointing to the Burr Oak. “This one stays.”

American Elm | Corner of Madison & Forrest Street

In the northwest corner of this intersection, adjacent to a rarely used parking lot, stands an American Elm, 48 inches in diameter, more than 100 feet tall and 100 years old. What’s notable about this tree, however, is what it has survived. “This tree is a fighter. This whole area was an industrial wasteland, with Phoenix Steel, NSP, and even a gas station at one point.” Even with all that pollution, this is perhaps the only tree to have weathered most, if not all, of the history of downtown Eau Claire. The traffic raced by on Madison Street as we craned our necks upward, just as it does every day. How many hundreds of thousands of people have driven by this tree over the years? After Matt’s tour, instead of ignoring this tree like everyone else, I give it a little nod when I pass. It deserves all the acknowledgment it can get.

Northern Red Oak | Owen Park

Owen Park is probably the best spot for locals looking to get into the tree appreciation game. This piece of land has been protected ever since it was donated to the city by John S. Owen in 1913, so it’s had the chance to grow some pretty impressive trees. Matt drove us along the bike path (“One of the perks of driving a city vehicle,” he said), and parked alongside the bathroom building south of the bandshell. We exited the truck and he pointed out a Northern Red Oak across the blacktop trail. “This is the 11th largest specimen in the state,” said Staudenmaier. “Maybe it’s even higher, as they haven’t conducted the survey in several years.”

Gingko Biloba | Owen Park

To the left of the entrance to the Eau Claire County Courthouse stands a tree that is not especially large or outwardly impressive. Also, that afternoon appeared to be an especially busy one, as far as county business was concerned, so we did a simple drive-by. But this non-native Gingko tree stands out regardless. “This tree is about 30 years old,” Staudenmaier pointed out, making it one of the city’s first attempts at biodiversity, back when that idea was something revolutionary.

Cottonwood | Chippewa River State Trail

Just west of UW-Eau Claire’s Haas Fine Arts Center, the bike trail forks. The upper path leads to the university, while the lower path snakes closer to the river. On the lower path, immediately after the division, tree enthusiasts will find a massive cottonwood tree. “This is the perfect spot for this type of tree,” Staudenmaier pointed out. The trunk is so large, in fact, that it can (and occasionally does) house people in an open spot near the base. On this occasion, we didn’t leave the path to see if anyone was home. But if I ever need a place to hide, I’ve got one now.

Barstow & Lake Street, Downtown Eau Claire

Trees of Eau Claire’s Future

As our tour left downtown and headed towards Shawtown and Eau Claire’s west side, Matt offered me a crash course in urban forestry. “The field originated with Dutch Elm Disease,” he tutored, explaining how this pathogen decimated elm populations throughout America in the 20th century, prompting cities and scientists to start exploring how to protect trees in urban and suburban spaces. This makes urban forestry a relatively young profession, and city arborists are still experimenting with the best methods to accomplish their goals.

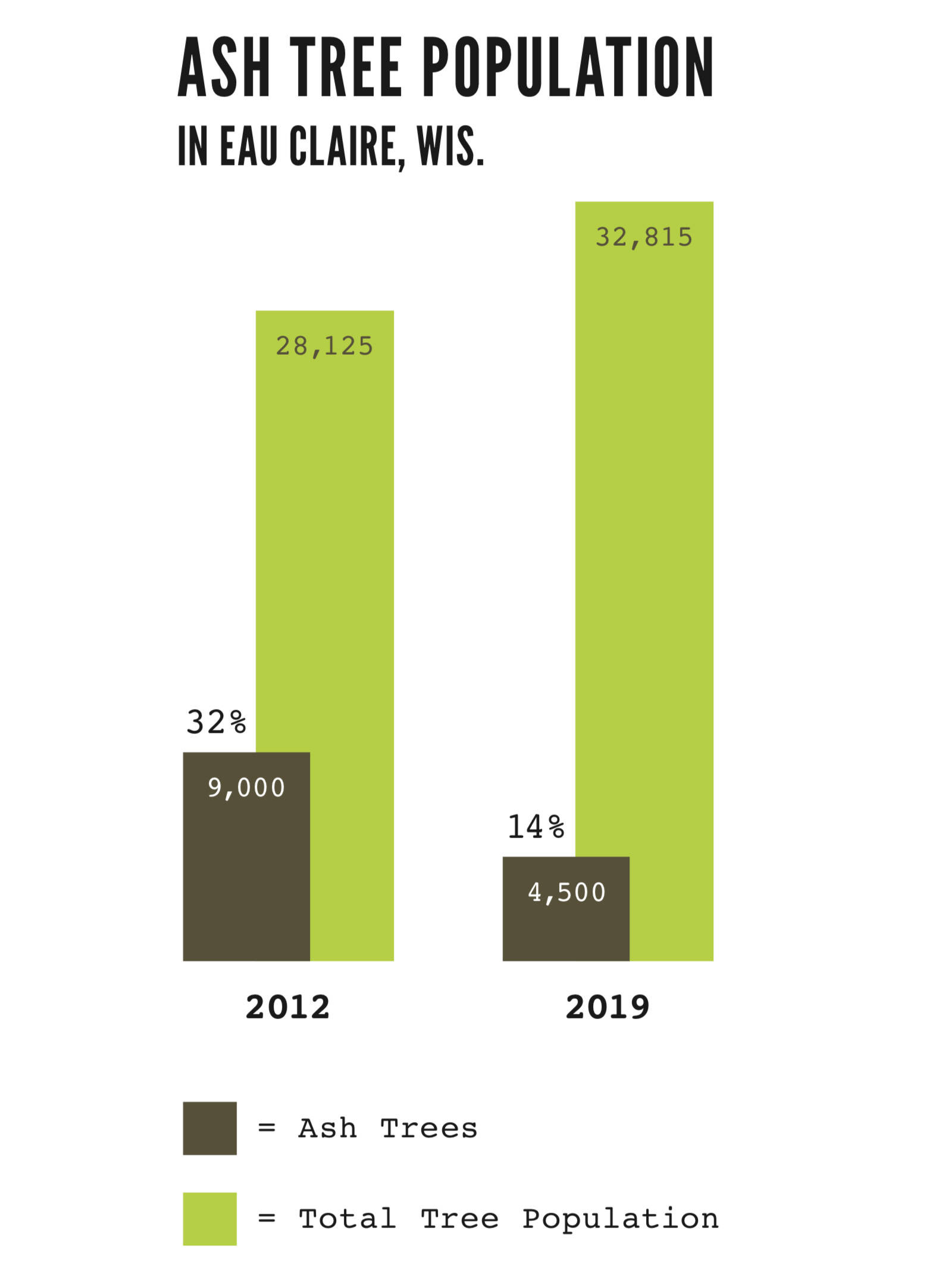

This brings us to Matt’s career-defining moment: the arrival of the emerald ash borer in Eau Claire county. “We first spotted borers in the ash trees outside Haas Fine Arts Center”– just up the sidewalk from the giant cottonwood tree.” Seven years ago, the city had about 9,000 ash trees. Now, we’re down to about 4,500.”

Many are familiar with the Forestry Division’s approach to the invading insect, which involves cutting down as many ash trees as they can and replacing them with a much more diverse mix of species. What residents may not realize, however, is that this approach is quite controversial. “We’ve had groups from as far as England come to learn about our ash borer program,” said Staudenmaier, and many of these visitors were shocked to learn of Eau Claire’s methods. The forestry department’s job is to protect the trees, after all, not cut thousands of them down.

But Staudenmaier has a reason for this drastic approach. Before the start of the abatement strategy, ash trees made up about 32% of all the trees on municipal land (excluding forests) in Eau Claire, constituting the sort of monoculture that invites problems like predatory insects. “Eau Claire has another dirty secret,” admitted Staudenmaier. As prevalent as ash trees were, maple trees are even more so, he said: “Up until a few years ago, almost one out of every two trees in Eau Claire was a maple.” This means that when something comes along to attack the maple trees (and Staudenmaier insists something will, someday), the local tree population will be much more devastated than it was by the ash borer or our defensive strategies. “The ash borer was kind of a happy accident,” said Staudenmaier. “It gave us an excuse to diversify, potentially saving us from much bigger problems in the future.”

Autumn in the Chippewa Valley is a great time to reconnect with our trees. Look up and appreciate the colors, which may make all the raking a little more palatable. And if you want to take it even further, the Forestry Division website features resources to help decide what sort of trees to plant. And this, perhaps, is the true pride we can take in being a Tree City: putting in the work now to provide shade and majesty for generations to come.