‘What Would You Get on the Bus For?’

author records personal stories of Civil Rights-era Freedom Riders

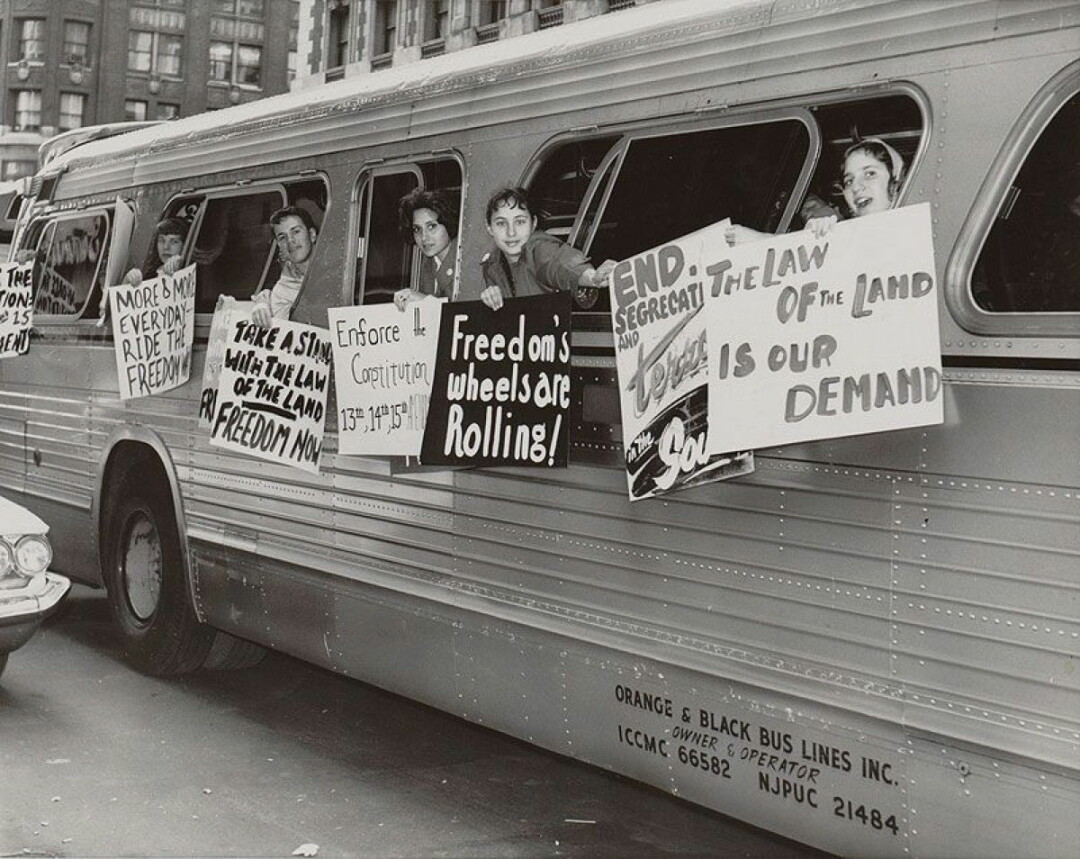

Throughout the summer of 1961, groups of volunteers – black and white, young and old, men and women – boarded busses. They were doing the unthinkable: testing a pair of U.S. Supreme Court rulings by integrating the buses for interstate travel. Calling themselves the Freedom Riders, they knew their destination would likely be prison at best, or death at worst.

“As a white person, you can use your privilege as a shield to hide behind or as a sword to fight injustice. The more I learn about these events, the more I recognize the privileges I hold and the more I want to be vocal about it.” – B.J. Hollars, author, The Road South

Textbooks tell the story of the Freedom Riders; they’re a famous group. But little is known about them as individuals. With his new book, The Road South: Personal Stories of the Freedom Riders, B.J. Hollars aims to change that. The topic caught his interest when he found out one of the Freedom Riders had lived in Eau Claire and attended his church. Starting with that man, Jim Zwerg, Hollars met with Freedom Riders and other key figures from the era to put together their personal histories, while grappling with his own convictions on race and civil disobedience.

When Hollars gets rolling, it’s best to get on board. The UW-Eau Claire English professor and Chippewa Valley Vanguard Award winner has authored and edited 10 books, many of which required thorough immersion research. The Road South is no exception. In it, Hollars proves manic enough to track down every lead, taking two different pilgrimages to the South to get every angle on his topic. Yet he’s affable enough to be taken in and trusted, connecting with his subjects – many now in their late 70s – and getting them to share their stories and their lives.

And after tracking down so many people for interviews, Hollars is an easy interview himself, eager to talk about this topic with plenty of anecdotes from the adventure. In his living room in Eau Claire, he explored a range of topics – mixing enthusiasm and serious focus in equal doses.

The motivation to write the book came from the desire to connect with history, not through a textbook, but through face-to-face interactions:

Hollars: “As someone who’s holding firmly to his relative youth, I just don’t think I have a great sense of history – whether that means 50 years or 100 years or more. Whereas the news cycle can lead you to believe one thing, talking to someone who has seen first-hand with his or her eyes the changes, or not, that have occurred in America over the past 50 years made for a really powerful experience. And it was able to open my eyes in a way that felt candid and sincere and organic. And I think that’s sort of the perspective that you lose unless you are having a personal conversation with somebody. And that’s what people like (Freedom Rider) Jim Zwerg provide me with – that kind of unadulterated personal story, not just about the events … but about the feelings behind the events which they participated in.

“And I think that is the premise of the book. Historians have written better books on the Freedom Riders, but I think this is the first time that someone really tried to go in-depth on the personal side of things. Not just what that person did at that time, but where that person is today … and what kind of convergence of events led that person to get on the bus in the first place. So that’s really where my heart was: trying to connect with humans on a human level to try to figure out what it takes to have that kind of courage and that kind of conviction.”

On being a white person assuming the role of Civil Rights storyteller:

“As a white person, you can use your privilege as a shield to hide behind or as a sword to fight injustice. The more I learn about these events, the more I recognize the privileges I hold and the more I want to be vocal about it. My story, in many ways, is negligible, but if I can use any of my modest skills to tell more important stories, especially from voices that might be underrepresented … what a gift that is. And what a privilege, too.

“A big goal of this book was to try to let the Freedom Riders tell the stories in their words and to try not to muck up the gears and get in the way too much. But at the same time a part of the story, too, is me coming to terms with how I feel about the state of the world, and what I want to do, and how I want to raise my kids. (Freedom Rider) Charles Person asks a powerful question: “What would you get on the bus for?” And when you have a Freedom Rider who was beaten within a few inches of his life looking you in the eye and asking what would you get on the bus for … that’s a question you take seriously.

“Now more than ever people need to confront that question, not just as a hypothetical but as a real question with real action behind it.”

And it’s important to remember that the Freedom Riders were a group of black and white people working together, and that white people bore considerable risk, too:

“According to (white Freedom Rider) Jim Zwerg, there was a hierarchy. When the mobs attacked, they would go for the white men first because they were the traitors to the race…followed by African-American men and African-American women, and finally white women. I remember Jim’s voice shaking when he told me that. And I imagine his mind was going back to that day in Montgomery at the bus station when that was proven to be true.”

Jim Zwerg and future Congressman John Lewis were seatmates on that ride, an image Hollars sees as an important symbol:

“There’s a famous photo of the two of them, and in it, Jim Zwerg has a hand to his mouth and John Lewis is holding is holding some kind of blood-covered bandage on his head. For me that’s an illustration of what the Rides represented. Here’s a white person, and here’s a black person…and they’re from vastly different backgrounds – one born in a small town in Alabama, one born in a midsized city in Wisconsin – both of whom cared enough about equal rights that they were willing to sit side by side and get beaten side by side to make sure that our country moved in the right direction.”

Several times in the process of researching and writing this book, current events showed America has not put racism in its review mirror:

“It’s hard for a white guy like me to know because I’ve never experienced discrimination first-hand. When I talk to Freedom Riders about this very question, their answer is usually mixed. ‘Yes we have come a long way but…’

“One of the Freedom Riders said to me, ‘I fought for this stuff 55 years ago and I’m afraid I’m going to die still fighting for it.’ And that’s such a heart-breaking thing to think about. So many folks have dedicated their entire lives to being activists and at this chapter in their lives, all that hard work hasn’t yet achieved the end goal.”

Hollars said that he considers the book a collaborative effort and that the relationships went beyond the page:

“There’s nothing more exciting than feeling that buzz in your pocket, looking down at your phone and seeing it’s Bernard LaFayette or Bill Harbour or Jim Zwerg. Or when you open your email and popped in your inbox is an email from Mimi Real or Susan Wamsley. These were Freedom Riders who had major roles in our nation’s history, though you may not know all of their names. Certainly, some Civil Rights leaders are always at the forefront of our minds, but beneath that group of people there are hundreds of others whose names you may not know and whose stories you might not know. And for me, getting a chance to know them – not just on a human level but almost a social level, where we might email each other or call each other just to talk about what we saw on the news that day. There were instances where I’d get a call from a Freedom Rider in the aftermath of a police shooting or one of the more divisive events in recent history just so he or she can share his or her perspective on that and ask me what mine is. In a lot of ways I don’t share a lot in common with some of the Freedom Riders in terms of age or region in which I live, but that’s what makes it a fun friendship. They can ask, ‘What are people in Wisconsin saying about this? What do people like you think about this?’ And I can ask similar questions and have an honest conversation.

“Part of the problem of writing a book is to find a way to ingratiate yourself to a person who five minutes before was a complete stranger. You have to make it apparent that you’re not just mining that person for information, that you care about them on a human level. The fact that we are keeping in touch well beyond the book’s publication, well beyond the final word, to me speaks to that continuing relationship. For me that’s just as exciting as the words on the page.

“The follow up is important. If you can get a friend out of it, all the better.”

And when Hollars turns the group into individual stories, the history becomes personal:

“I’d like to think of this book as a collaboration. Certainly, it never would’ve been possible without the support of the Freedom Riders who I interviewed. And perhaps by working together, we were able to more fully tell the story of the larger movement by way of the more personal stories.

“You can hear all about the firebombing and the bus bombing and all of these things, but I’m really curious about what Mimi Feingold was thinking and feeling when she looked out the window that day in Montgomery. That’s the kind of stuff you won’t find in a history book. For me, homing in on an individual opens up the story in new ways.

“Something I didn’t understand prior to the interviews was just how much was at stake. Jim Zwerg talks about his parents and how they reacted to this. Others talked to how their parents reacted and how in some instances their parents were threatened that they would lose their jobs and everything else. And some were threatened with expulsion and in fact were expelled. There were real life repercussions for themselves and their family members for taking this risk. That’s a form of bravery that extends well beyond just taking a seat on a bus.”

One of the reasons people opened up to him was to keep their stories alive:

“People seemed really willing to share because one thing that seemed true of everyone I talked to was the sentiment that their story was being lost. And some of them were almost visibly angry by that. Some of them took the blame themselves: ‘We’re the ones who dropped the ball. We’re the ones who were so busy trying to make ends meet, trying to feed our families, trying to work our jobs, trying to support the cause when we could, that we didn’t have time to pass the story on to the next generation.’ That was something that really seemed to haunt some of the Riders.”

In the end, it’s a story of individuals making the choice to band together as one:

“There was this incredible humility going through these conversations. I’d be a bit star-struck sitting across the table from (Freedom Rider) Catherine Burks-Brooks. She would wave me off so quickly: ‘Oh it’s just what we did. We had to do it. If not us, then who would do it?’ That was a famous line from John Lewis.

“These are people who just stepped up. Some of them joked that they were young enough and reckless enough to be the perfect people for the job. But reckless or not, there was courage in their actions and if it wasn’t for that quote-unquote recklessness, the changes would not have been enacted in the way that they were. They sped up the process dramatically.

“I think that’s where that modesty comes from – the fact that the Riders view themselves as a collective: We did it. We did it. I never heard anyone ever say I did it. It was always we got on the bus. We were beaten. We retreated to the church. It’s a reminder that there’s power in people. There’s power in a person, but there’s more power in people.”

B.J. Hollars will read from and sign his new book, The Road South, at 7pm Thursday, May 10, at The Volume One Gallery at The Local Store, 205 N. Dewey St.