Max Garland's New Book the Product of False Starts, Luck, and Persistence

Marie Anthony, photos by Andrea Paulseth |

If I hadn’t met Max Garland before I read his book of poetry, The Word We Used For It, I would have believed that words came effortlessly for him, always. Isn’t that how it is for poets laureate who win prestigious awards like The Brittingham Prize? Sometimes. Maybe. But in truth, it turns out that even poets laureate can find their words lost, or as Garland describes: “My writing process is based primarily on false starts, dead ends, pipe dreams, persistence, and once in a while, luck.”

Maybe luck played a part in Garland winning the Brittingham Prize – which is awarded by the University of Wisconsin Press and entails the publication of the winner’s work – but I think he has a true gift. Luck is only but a wee piece of his success. I was curious to know if winning an award like this changed Garland’s perception of writing in any way or if he felt any different about himself. For him, what meant the most was that his words were accessible to others. “The poems get to see the light of day,” he says, “You think and write and revise, but poems get to have different lives once others read or hear them. They’re not just yours anymore.”

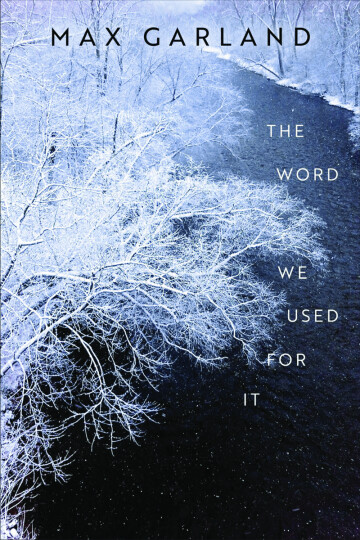

On Friday, Nov. 10, Garland will release his book, The Word We Used For It. The release party and book signing will be held at the Volume One Gallery, 205 N. Dewey St.

This collection of poems, Garland says, “grapples with memory, how imagination shapes memory. How we continually revise what we remember, not necessarily to deceive ourselves, but in order to find meaning.” He also tells me that this collection of poems is not necessarily different from others he’s written. “I once thought each book should be very different,” he says. “But, I’m starting to believe that (we’re) just stuck with (our) obsessions. It’s fine to revisit, maybe dig a little deeper into familiar territory.”

If Garland had to pinpoint one distinction in this collection of poetry, it’s that there is more science in it. He says that he’s always been drawn to the distant and exotic things that are connected to us. Fascination with space fashioned Max’s childhood, as he grew up during the space race. He tells me that he used to think science was removed from writing. “But I’ve gotten more confident writing about space,” he says. “I think creativity is important in science.”

As for what’s on the horizon for his next project, Garland says that “the project is always the same – to get lucky enough with language to say something useful.” He’s always working on new poetry and songs, but he also spends time sifting through old journals, “separating the wheat from the chaff.” It’s important to him to fashion his thoughts in ways that are meaningful to readers. “I’m completely open to any resonance people find or feel. I do hope my own observations and words strike an occasional familiar chord in others. I like poems that initiate surprise in the midst of familiarity,” he says.

I spent much of my day with Max Garland and his words. While I caught the occasional breeze on the back of my neck, or the hum of the refrigerator in the night, I found myself lost in them. Sometimes surprised, sometimes curious, sometimes in awe. It was a beautiful thing to find myself immersed in his memory and imagination and to forget – even for short moments – all of the noise in this world. As Max so beautifully puts it, “Poetry matters now because every day we are bombarded with sales pitch, babble, and weaponized words. We need more language that helps sweeten, rather than degrade human discourse. Poetry, at its best, allows imagination to widen our horizons. It connects rather than isolates. Poetry matters because words matter, and words matter because human beings matter.”