Historic Training: UWEC history students seek national recognition for city’s railroad sites

Tom Giffey, photos by Tina Ecker, Janae Breunig, Andrea Paulseth |

Physical reminders of Eau Claire’s railroad history are still around if you know where to look. Now, a UW-Eau Claire class is working to ensure that these sites are recognized, preserved, and interpreted for future generations.

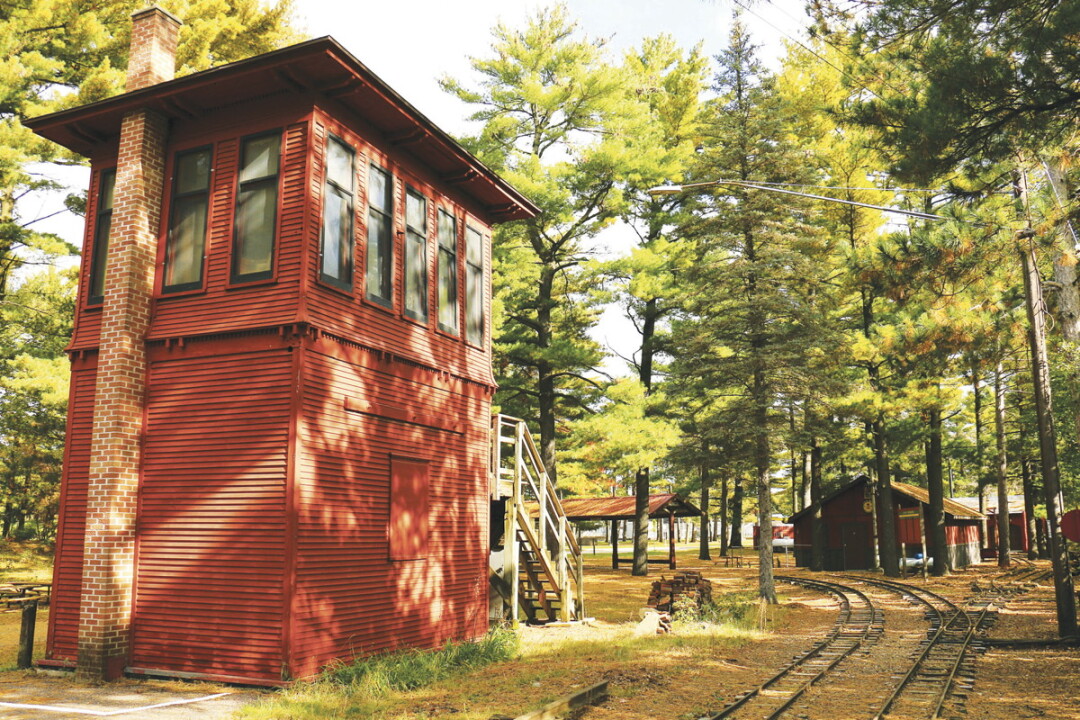

A dozen students in Professor John Mann’s public history seminar are beginning the process of researching three sites with the goal of nominating them for addition to the National Register of Historic Places: the Chicago & North Western Railroad Tower in Carson Park, the former Soo Line “S” Bridge near Banbury Place, and the so-called High Bridge that was once part of the Chicago & Northwestern line. All three sites were designated local landmarks last year by the Eau Claire Landmarks Commission – which Mann chairs – but adding them to the national list will give the structures additional recognition and protection, Mann said.

“The designation will mean that the information about the structures will be recorded for posterity,” Mann explained. “It is mostly honorary, though listing will make the structures eligible for certain grant funds.”

“The designation will mean that the information about the structures will be recorded for posterity.” – John Mann, UW-Eau Claire history professor, on getting several Eau Claire sites on the National Register of Historic Places

In addition to researching, preparing, and submitting applications to the National Register, students in the seminar – most of whom are pursuing undergraduate degrees with an emphasis in public history – will also write essays related to the Yellowstone Trail, one of the first designated coast-to-coast highways, which passed through Eau Claire. These essays may be included in a future book on the trail, Mann said.

On a recent afternoon, the students explored all three historic sites in person. Their first stop was Carson Park, where the railroad tower is part of the Chippewa Valley Railroad, which operates miniature steam and diesel trains each summer. The tower, which was built in 1896 near what is now Banbury Place, was moved to the park in 1991.

David Peterson, president of the Chippewa Valley Railroad, guided the students up a wooden staircase and into the tower, which is usually closed to visitors. Inside, he described the vintage equipment that once was used to signal trains as well as to switch them from track to track. He invited a student to try to shift one of the huge levers. The young man strained mightily, but was unable to.

“C’mon man, the 400’s coming, there’s gonna be an accident,” Peterson joked, referring to the legendary Twin Cities 400, which in the mid-20th century whizzed through Eau Claire on its way from Minneapolis to Chicago. After a round of chuckles, he acknowledged that the particular lever was probably immovable. Over the coming years, he explained, the Chippewa Valley Railroad plans to restore the tower inside and out and to get some of its equipment working.

When it was decommissioned in 1991, it was the last operating railroad tower in Wisconsin, and – if restored – it would be the only one in operation. The tower is also historic for a technological reason: In 1901, it became the first tower to be outfitted with an electric interlocking system by the Taylor Signal Co. That meant that the tracks were switched by electric power, rather than by hand, which made them safer and easier to operate.

Students said the seminar is giving them the kind of firsthand experience with conducting historic research and working with the public that they will use in their future careers at museums, archives, or historic preservation groups.

Tyler Shustarich, who is part of the student team researching the tower, said he and his classmates are delving into a stack of primary documents provided by the Chippewa Valley Railroad as well as searching secondary sources, such as contemporary newspapers, for details about the tower’s history.

“The hardest part for ours is that it was moved from the original spot,” explained fellow student Erica Shrader. While relocation typically disqualifies a structure from being included on the National Register, classmate Nate Why pointed out that, if it hadn’t been moved, the tower likely would have been demolished. Furthermore, gaining National Register status for the tower would preserve it for the future. “The most important thing is these (structures) can’t go anywhere once they’re on there,” Why added.

The process of getting the tower and the two bridges, which are now part of the city’s bike trail system, on the National Register will extend beyond the end of the class. Mann explained that first the applications will be considered by the state. If approved there, they will be forwarded to the National Parks Service, which administers the National Register. If the students’ applications are successful, approval will take at least a year.