Why the River

local waterways show us strange things in the spring

Mike Paulus, illustrated by Serena Wagner |

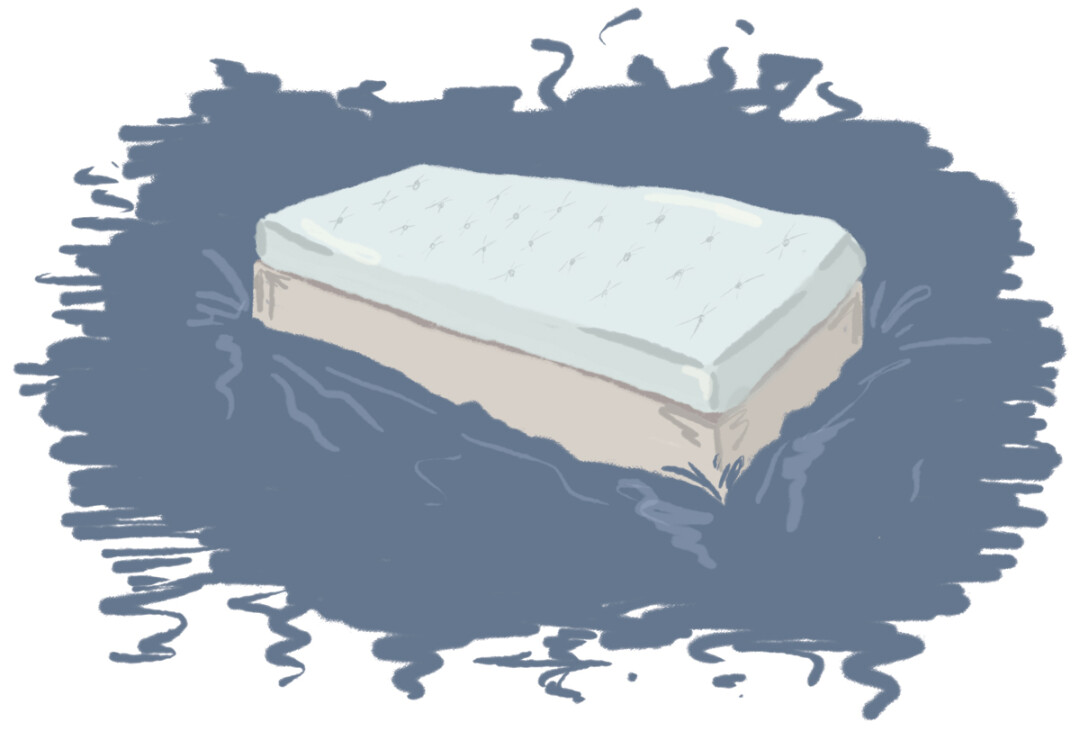

I’m pretty sure we saw a full size bed floating down the Chippewa River last week. My wife and I had just driven onto the Madison Street bridge when she immediately saw it. And since I have the eagle-eyed eyesight of a very old, very handsome, very blind eagle who can no longer fend for itself, it took me almost the entire drive across the bridge to spot it. So I can’t be positive, but I’m almost sort of absolutely sure that what we saw sloshing through the surging current was the remnants of a box spring and its bed frame.

It’s possible someone threw the thing down along the riverbank, looking for a cheap-n-easy method of disposal that slaps Mother Nature right across the face. Maybe they had to move out of their house and didn’t know what else to do. Or maybe someone was living in a cave along the banks of the Mighty Chippewa when they got the rudest wake-up call Old Man River could provide.

From these clouds, the moisture rains back down, filling our rivers and streams to the point of flooding, and that’s why the tennis courts by the Water Street bridge look like a slimy abandoned fish hatchery.

Or maybe it was just some other hunk of junk that just shouldn’t be in the river, and not a bed at all. I’m usually mesmerized by entire trees snaking their way through the rushing waters of the Eau Claire and Chippewa rivers. They make their way through the heart of Eau Claire, their gangly branches waving to us as we saunter down the bike paths. Sometimes they get hung up on the rotund concrete legs of a bridge, and they stay right there all summer long after the waters calm down.

That’s trees. A bed? That’s weird. I guess the river didn’t like it where it was. That’s what rivers do. They move stuff.

Rivers need a good washout from time to time. They gotta keep the way clean and clear of debris. Obviously, major floods can be devastating to communities. But for the river itself, an annual gush of springtime melt water – or an occasional massive summer rainstorm – helps to keep the system healthy.

This is probably a good metaphor for what we Wisconsinites do each spring when we clean our homes, hold garage sales, and try to reassess our post-winter mental health.

Someone should totally write about that.

Anyway, you may be asking yourself, How does this springtime flooding work? Exactly where does all this extra water come from? The answer is simple:

Each winter, the ground freezes, trapping a remarkable amount of moisture in the soil, creating a massive layer of ground frost 30 to 60 feet deep across the Upper Midwest. In March, the Earth moves back into its “warm orbit” around the sun, and – coupled with intense heat produced by increased foot traffic from tiny forest animals as they wake from hibernation – this causes that frost layer to melt within the span of a few days. This annual period of mass thaw is what our French fur-trading forefathers so quaintly called “Une Grande Fête Pour Le Temps Massif Slushy De La Terre.”

They also called it the “Slush Fleur,” aka, the Slush Blossom.

Soon after the Slush Blossom blooms, the planet’s annual intensified rotation whips the Midwest around and around like a gargantuan, gravity-powered salad spinner, shooting all of that cold water up into the atmosphere, where it forms clouds. From these clouds, the moisture rains back down, filling our rivers and streams to the point of flooding, and that’s why the tennis courts by the Water Street bridge look like a slimy abandoned fish hatchery.

I haven’t studied geology or meteorology since my sophomore year of high school, but I’m pretty sure that’s how it all works.

Anyway, you may be asking yourself, What happened to the bed in the river? Good question. Without a doubt, I honestly don’t know. I wish I did. I hope it finds someplace safe to come ashore. I hope some kind soul finds it and caries it off to a comfy landfill or maybe to a junk sculptor who can shape it into the wings of an enormous garbage eagle that stays perched beside the river, keeping an eye on things, watching for more its kind.

One can only hope.