The Land Towards Which They Were Going

the story of James Zwerg, a Wisconsin freedom rider

In late February 1961, 21-year-old James Zwerg – a native of Appleton – took his place in a Nashville, Tennessee, movie theater line alongside all the rest. The tall, white Midwesterner was quiet but anxious, confident though a little afraid. To the ticket seller at the front of the line, his exterior surely pegged him as the perfect patron – clean-cut, attentive, and, as his skin color confirmed, certainly not one of those black agitators who had so forcefully been integrating lunch counters over the past year. Indeed, he appeared to be just another white moviegoer, his outward appearance offering no hint of the convictions the young man held in his heart.

Eventually Zwerg made his way to the front of the line, purchasing a pair of tickets without incident. Then, he did so again, and again – six times total – until the theater manager noticed the gathering demonstrators, sensed Zwerg was among them, and refused to sell the white man any more tickets for him to distribute to his rabblerousing friends. His cover was blown, though for Zwerg, there was no turning back.

Zwerg joined his fellow demonstrators, handing a ticket to African-American Bill Harbour, his previously assigned partner in testing the facility. Both were members of the Nashville Student Movement, and in the preceding weeks, had endured an intense regimen of nonviolent workshops to prepare them for this moment.

Armed only with their nonviolent training, Zwerg and Harbour strode toward the doors. Though the men undoubtedly tried to hide their fear, they surely felt it. After all, they were preparing to undertake a dangerous mission, one sure to violate both custom and law in an effort to combat segregation.

“We got inside the doors,” Zwerg remembers 54 years later. “Then we were both cold cocked and dumped out on the sidewalks. And that,” Zwerg explains, “was my introduction to being a demonstrator.”

James Zwerg’s transition from modest Midwesterner to civil rights activist was unexpected, a personal journey that began three years prior at Beloit College, where he witnessed his roommate, African-American Bob Carter, discriminated against on a regular basis.

“We’d go to the commons to have a meal and people would get up from the table to leave,” Zwerg recalls. “And there were these excessive tiffs during basketball or football intramural games. People made comments just loud enough for him to hear.” Soon Zwerg observed instances of discrimination spilling into the city as well, including one situation in which a barber refused to cut Carter’s hair. Despite these trespasses, Carter only ever responded with silence, a choice that proved puzzling to Zwerg.

One day while lounging in their dorm room, Zwerg asked, “How do you take it? Why don’t you do something?” In reply, Carter marched to his dresser, removed a copy of Dr. Martin Luther King’s Strive Toward Freedom, and encouraged his roommate to read it.

Zwerg did, and though King’s account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott provided him deeper insight on nonviolent protests, the young college student still struggled to understand the strategy’s effectiveness. “I could understand the boycotts …” Zwerg explains, “but this nonviolence business, I didn’t really get a good handle on it at that point.”

Nevertheless, it was enough to stir his consciousness.

“It got me wondering,” Zwerg recalls, “how I would feel if I was in the minority.”

For years to come, students in Eau Claire likely learned of the Civil Rights Movement the way many students do: while seated in their high school history classrooms, overwhelmed by the many marches and bombings and beatings, all of which have become hallmarks of the movement. As a result of the movement’s many fronts, that first mention of Freedom Rides – rides that ultimately led to integrating interstate bus travel – often becomes a bit blurred, one more battle amid the larger war. At least that was my experience, one that prompted me to reduce the rides to a mere bullet point in my notebook. But between 1968-1971, perhaps Eau Claire’s students might’ve more fully given the Freedom Riders their due, especially had they known they lived among one.

Seven years after his time on the bus, Zwerg – then 27, married and ordained – left his parish in Pittsville, Wisconsin, to serve as an associate pastor at Eau Claire’s First Congregational United Church of Christ.

“Eau Claire had such wonderfully, wonderfully warm people,” Zwerg tells me in a recent phone interview, “and they were very accepting.” He remembers the congregation consisting of many university students and professors, all of whom challenged him to come up with thoughtful sermons week after week. In addition to his ecumenical work alongside local churches, for three years Zwerg also oversaw the business of “marrying and burying” the people of Eau Claire, tasks that, while seemingly perfunctory, he performed with great care.

All in all, it was a blissful time in Zwerg’s life, one made all the better by the births of two children. Despite his personal happiness, by 1971 his professional ambitions appeared to have reached a standstill. In late summer of that year the Zwergs left Eau Claire and moved to Tucson, Arizona, where the young pastor had accepted a position as head pastor at a different church.

“It was just one of those situations where I’d been an associate for three years and I’d done kind of what I could do (in Eau Claire),” Zwerg explains. “I met the goals I’d set for myself, and (the goals) I felt the church had set for us.”

“And also,” he admits a bit sheepishly, “my family and I were getting a little tired of the cold.”

Throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, Zwerg’s interest in civil rights continued to grow. So much so that in the spring of his junior year, Zwerg left Beloit College to take part in an exchange program with Fisk University, arriving at Nashville’s historically black school in January 1961. Upon entering the student union, it became clear to Zwerg that he was, for the first time in his life, the minority – a scenario he’d previously only considered hypothetically. Sensing his unease, a young African-American couple invited him to their table, and together, the trio engaged in casual chitchat, picking at French fries and watching as their fellow students crowded the nearby dance floor.

“What’s that?” Zwerg asked, curious about the dancing taking place before them.

“The twist,” the couple informed him.

“Oh, I know the twist,” Zwerg said confidently, though upon setting out to prove it on the dance floor, soon learned that his knowledge was limited to the “Wisconsin twist” – a variation that, as he put it, was “very flat-footed” in comparison to the dance being performed by the Fisk students.

Though what Zwerg lacked in twisting skills he soon made up for with his congenial nature. He was quick to befriend the couple, and in an effort to continue the fun as the afternoon wound down, invited them to join him for a movie.

The couple stared at him as if he was crazy.

“Jim,” they said, “we can’t take in a movie together. The movie theaters in Nashville are segregated.”

He was shocked, though perhaps he shouldn’t have been. After all, segregation had long been an accepted practice throughout the South, though as a white northerner, he hadn’t experienced such overt racism firsthand.

“Who are they to say who I can and can’t go to a movie with?” Zwerg grumbled, to which the young couple replied that if he was serious about integrating Nashville’s theaters, he was welcome to join SNCC’s effort to do so.

Zwerg agreed he’d give it some thought, though within a few months time, he’d give far more than that.

Zwerg’s time in Eau Claire couldn’t have been more different than his time in Nashville. In the South, he’d regularly witnessed racial confrontations, though given Eau Claire’s overwhelmingly white demographic, Zwerg has no memory of observing such overt displays of racism happening here.

“It wasn’t a terribly diverse church,” he tells me. “It was predominantly white.”

While issues of race remained close to Zwerg’s heart, on the local level, he found few opportunities to confront the subject head on. Following his time on the Freedom Rides, Zwerg tried to fill the void left behind by his activism with his pastoral duties, though that void would never be filled. Despite tending to various congregations over the years, he conceded that he never again felt as “spiritually alive” as he had while serving on the front lines of the Civil Rights movement.

In 1965, in the bloody aftermath of Selma-to-Montgomery marchers being beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Zwerg considered returning to the front lines yet again. Spurred by the shocking images they’d seen on television, pastors from the United Church of Christ had gathered to discuss what they might do to assist Dr. King’s effort.

“One of the pastors had gone down and marched with King for three hours and come back an expert,” Zwerg said, a hint of irritation in his voice. “A lot of people seemed to. He got up during the meeting and made this very impassioned plea that all the churches ought to let the clergy go down and march with King, and the more I heard about it the more it upset me.”

Zwerg felt strongly that a three-hour march through the South – followed by a quick retreat to the northern pulpit – ultimately did little to serve the movement. He believed the church needed to make an authentic commitment to the cause rather than resort to a gesture.

Zwerg shot a glance toward his wife who, upon catching his gaze, immediately began to cry, well aware of what her husband planned to do next.

“If you want somebody to go, I’ll go,” Zwerg informed his fellow clergymen. “But understand the way I’m going to go because I will go to the end. I’m not going for three hours or three days. I’m going for the whole thing.”

The room turned silent as all eyes focused on the former Freedom Rider – the man in the room who knew better than most what it meant to sacrifice oneself for a cause.

Zwerg steeled himself for the journey, though it wasn’t to be. By the time the logistics were arranged, the marchers had already arrived at their intended destination at the Alabama state Capitol.

Zwerg’s wife sighed in relief as her husband returned to his flock, to his duties of marrying and burying, and the movement moved on without him.

On May 16, 1961 – the night before boarding the Freedom Riders bus – Zwerg sat down to write a letter to his parents. Not just any letter, but a “last will and testament” of sorts, a letter to be given to his parents in the event that he was killed.

And there was reason to believe he might be.

Twelve days prior, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had begun a similar ride, sending 13 civil rights activists on a bus trip from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans. They never made it. The first bus was firebombed in Anniston, Alabama, while the second drove riders directly into the hands of a Birmingham mob. They hoped to continue the journey despite the violence, though their inability to find a bus driver ultimately stymied their efforts.

Zwerg and the other second-wave Freedom Riders were acutely aware of the risks they took in trying to continue CORE’s journey. Perhaps influenced by the uncertainty of what was to come, in addition to his letter, Zwerg felt compelled to pick up the phone and give his parents a call.

“I was naively hoping that I would get the kind of send off that the young soldier gets,” Zwerg explains. “‘We’re proud of you son, God bless you, keep safe.’ And … I didn’t get that.”

Instead, his mother interrupted him midway through his explanation.

“You can’t do that,” she said. “You’re throwing your education away. Think of the money we spent. And do you know what you’ll do to your father?” she asked, alluding to his heart condition. “He can’t take this. You can’t do this to him.”

Zwerg explained that he believed it to be God’s will – that he’d never felt so sure of anything – but she cut him off again.

“You’ll kill your father,’” she said, slamming the phone into its cradle.

Undeterred, Zwerg boarded the bus the following morning.

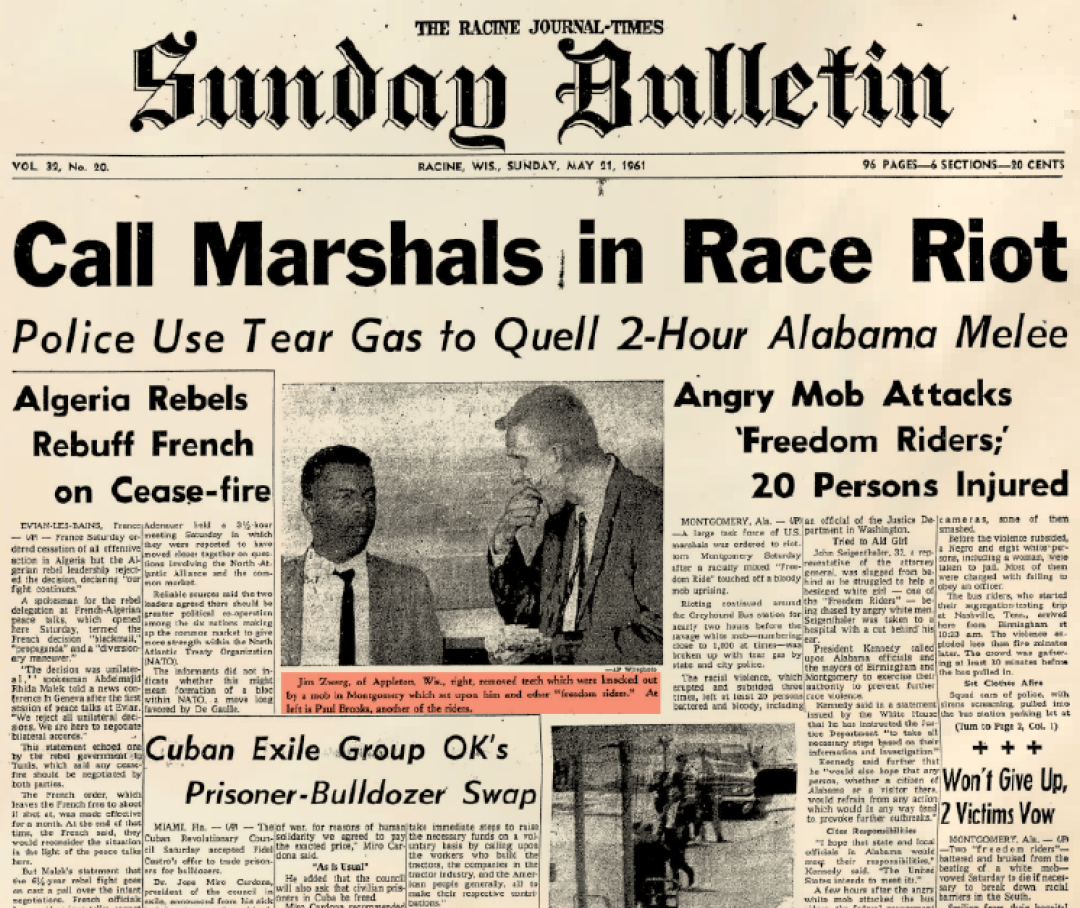

At the end of the first day of SNCC’s Freedom Rides, Zwerg and his seatmate, Paul Brooks, found themselves in jail. The bus had successfully traveled 200 miles, though upon arriving in Birmingham, Bull Connor, the city’s notoriously violent commissioner of public safety, immediately put a stop to what he viewed as a flagrant disregard for the law.

They were released two and a half days later, in which time the Kennedy administration had struck a deal with Alabama Gov. John Patterson, who agreed to protect the Freedom Riders during the remainder of their time in the state. As a result, on the morning of May 20, the Freedom Riders received an unprecedented escort as they journeyed deeper into Dixie.

“We had a plane going overhead,” Zwerg recalls, “we had squad cars, we had motorcycles.” Yet despite these momentary protections, their escort mysteriously peeled away just as they entered Montgomery city limits.

Suddenly the Freedom Riders were exposed, and they knew it.

Zwerg turned to his seatmate, future congressman John Lewis, to find he’d reawakened from his nap just in time to share Zwerg’s uneasiness. As the last patrol car pulled out of sight, Zwerg remembers Lewis saying, “That’s not good.”

The bus eased into Montgomery’s Greyhound station at around 10:20am, and though they feared for their lives, the Freedom Riders had no choice but to disembark. Zwerg exited the bus moments after Bill Harbour. Months prior, their nonviolent tactics had been tested at the Nashville movie theaters, and by the looks of things, Zwerg began to think they might just be tested again.

The Freedom Riders huddled close around the press conference’s microphones, uncertain of what was to come.

“John was just stepping forward to address the press,” Zwerg remembers, “and this fella – I think he was a used car salesmen as I recall, and a Klansmen – went at one of the fellas with a parabolic mic, grabbed it, and threw it to the ground.”

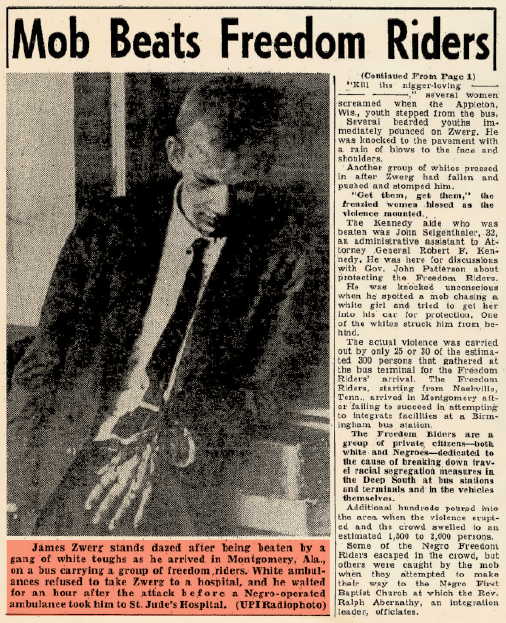

It was the spark that lit the fire, spurring a mob 200 strong to emerge from all sides of the station, shoving the press out of the way and moving toward the Freedom Riders. The following day’s edition of the Anniston Star described the “howling mobs of white people” that raged for two hours, the women who attacked women with their purses, as well as the men who attacked the man who tried to stop it. Zwerg was in the midst of the mob, watching in horror as they came bearing bricks and pipes and chains – all of which they used indiscriminately.

Zwerg remained motionless as they swarmed around him, praying to God for the strength to remain nonviolent in the midst of mortal danger. But as the men closed in he prayed also for them, asking God to forgive them their trespass.

“And that’s when I had this incredible religious experience of feeling surrounded by love and peace,” Zwerg says. “I just had an assurance that no matter what happened I was going to be OK.”

Following his beating, Zwerg’s bloodied photograph would grace newspapers across the country, though often even his neighbors and friends remained unaware of the dramatic role he played in integrating interstate bus travel. Yet Zwerg’s anonymity was of his own making. His infamous photograph had made him a reluctant icon in a movement much larger than he. It was a role that made him uncomfortable, though the photo would serve an important purpose for the movement: rousing white moderates from their passivity and forcing them to grapple with their own inaction.

A second equally powerful photo was published just a few days after the first. In it, a bruised and seemingly unconscious Zwerg is seen in his hospital bed, a copy of The Montgomery Advertiser – featuring the previously published photograph of a blood-covered Zwerg – balanced in his hands. The photo offered viewers access to two James Zwergs: one bloodied, one bruised, but both seemingly unmoved in their conviction.

His conviction for the cause was reaffirmed during a hospital bed interview offered soon after his attack. In the footage that remains, a black-eyed Zwerg can be heard saying, “We’re dedicated to this. We’ll take hitting, we’ll take beating.” And then, as Zwerg’s half-closed eyes flash directly to the camera, he delivers his most powerful line of all: “We’re willing to accept death.”

These days, few Eau Clairians still remember James Zwerg, but one man, Jerry Foote, will never forget his former associate pastor.

“We were friends,” the retired biology professor informs me. “My wife and I visited him in Tucson years later.”

Foote, a young man himself in 1967, still remembers Zwerg’s powerful pastoral style.

“What was it Jim used to say?” Foote asks, turning from the phone’s mouthpiece to confer with his wife. I hear a muffled reply, followed by: “He used to say pastoring was like acting. That it was about holding the audience’s attention,” – something that, according to Foote, Zwerg was quite good at.

When I ask him to tell me more about who James Zwerg was, Foote pauses before continuing.

“Let me tell you a story,” he says.

Foote goes on to describe one particularly blistering Eau Claire winter in which the snow piled so high on the rooftops that citizens took to their roofs with their rakes.

“The snow must’ve been waist high,” Foote remembers, “and I helped Jim rake his whole roof. And then, after we finished, he came over to help me rake mine.”

I smile at the image of the two men sharing roof-raking duties, an image not altogether rare in these parts.

“During all the time you spent with him,” I continue, “did he ever mention his experiences on the Freedom Rides?”

“He didn’t,” Foote says. “In fact, I didn’t know anything about it until years after he left.”

On a warm Sunday in July, I slip inside Eau Claire’s First Congregational Church on Broadway Street, anxious to hear a sermon in James Zwerg’s former spiritual home. I take my seat, and though I try to blend in, given that I’ve selected the less-popular early morning service, I immediately stick out among the early risers. I’m welcomed heartily, and as Rev. Mark Pirazzini begins his sermon, I can’t help but envision Zwerg standing behind a similar podium decades prior offering his own spiritual guidance.

On this day, the reverend’s sermon comes from the Gospel of John; specifically, the story of Jesus gathering five loaves of bread and a pair of fish and managing to feed the masses. And later, how Jesus walks on water to greet his disciples in their rocking boat, and how His presence alone is enough to steady the waters.

Rev. Pirazzini reads from the scriptures, describing how Jesus boarded the boat, and how as a result, He and his disciples eventually “reached the land towards which they were going.”

Once more I think of Zwerg, though this time, my mind’s eye doesn’t picture him as a pastor behind a podium, but as a 21-year-old college kid from Wisconsin. For a time, that’s all he was – just a college kid like all the rest. But then one day he boarded a bus during a tumultuous time and stayed steady as long as he could.

As a result of his injuries, Zwerg never quite reached the land toward which he was going, though the greater movement did. Despite this victory, to this day, Zwerg still regrets his inability to continue the ride alongside his brothers and sisters.

In 2001, he received a second chance.

In celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Zwerg and several of his compatriots boarded a bus together one last time, leaving from Atlanta to retrace portions of the original route. Along the way they paid a visit to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, where Zwerg gazed at black-and-white photographs of the people he once counted among his friends. As he passed a timeline on a wall, he was startled to see his own photograph staring back, a younger version of himself lying unconscious in a Montgomery hospital bed.

“I lost it,” Zwerg told me. “I just lost it. I started crying and said, ‘I don’t deserve this. I didn’t do that much.’ So many people had continued on … had literarily dedicated their lives. I felt I shouldn’t have this kind of notoriety.”

As he wept, fellow Freedom Rider Jim Davis engulfed him in a bear hug.

“What’s the matter, Brother Jim?” Davis asked.

Zwerg told him of his regret for having to cut the ride short on account of his injuries while the others rolled on without him.

“Jim,” Davis said, astonished, “you don’t realize it, but your voice from that hospital bed was our call to action. You,” he stressed, holding his brother tight, “you were with us the whole way.”

B.J. Hollars is an assistant professor of English at UW-Eau Claire. His books include Thirteen Loops: Race, Violence and the Last Lynching in America and Opening the Doors: The Desegregation of the University of Alabama and the Fight for Civil Rights in Tuscaloosa. Additionally, he has two books forthcoming in 2015: From the Mouths of Dogs: What Our Pets Teach Us About Life, Death, and Being Human, as well as a collection of essays, This Is Only A Test. Learn more about him at bjhollars.com.