Men, Not Monsters

UWEC lecturer examines lives of original Siamese twins

Tom Giffey, photos by Andrea Paulseth |

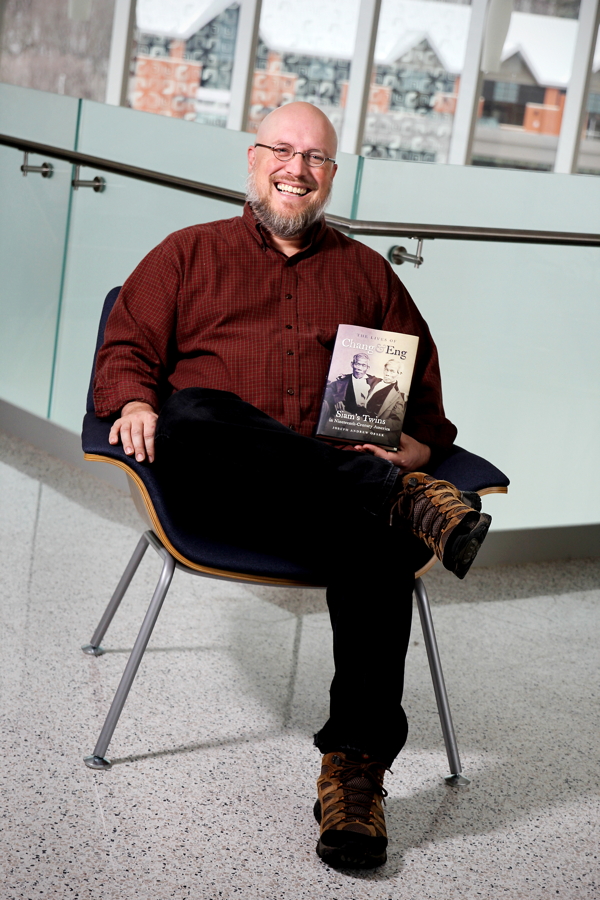

More than two centuries after their birth, Chang and Eng Bunker remain both enormously well-known and fundamentally unknowable. Reconciling these two facts was part of the challenge faced by Joseph Orser, a senior lecturer in history and English at UW-Eau Claire and the author of a new biography of the legendary brothers.

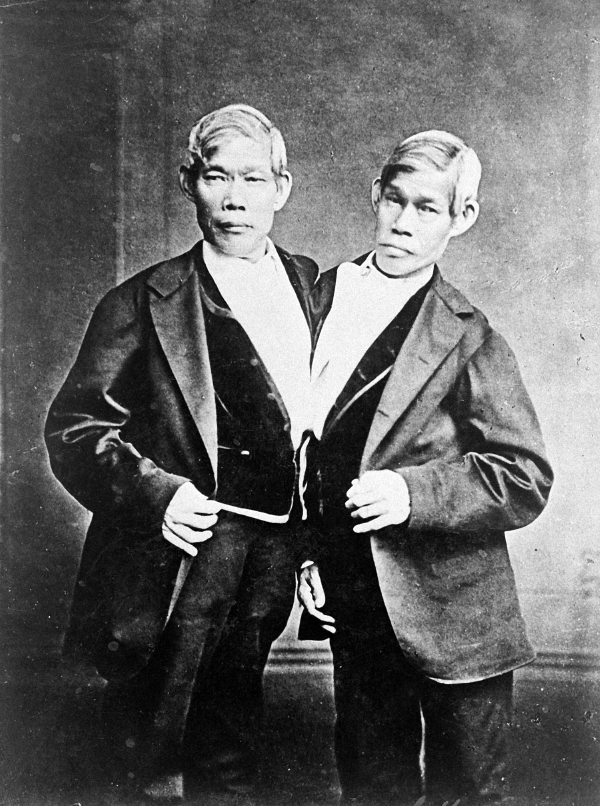

If the Bunkers’ names aren’t immediately familiar, that’s because you know them by their show-business label, which persists as a description for others born like them: Chang and Eng, you see, were the original Siamese twins. Born in 1811 in Thailand (then known as Siam), the twins were forever connected at the chest by flesh and cartilage. Their conjoined state (and, in the United States, their race) set them apart from all those around them, and it also set them on a path toward worldwide stardom: First exhibited in the United States as teens, the twins eventually took control of their own career, made a small fortune, then stepped out of the limelight and established themselves as country gentlemen, family men, and – in the years before the Civil War – as slave owners.

The twins’ colorful and contradictory life has provided fodder for prior biographies, novels, and plays, but Orser nonetheless found a largely unexplored angle for his work: His book, which he calls the first academic biography of the twins, uses their lives as a way to examine Americans’ perceptions about and treatment of Asian-Americans in the 19th century.

In fact, it was the twins’ arrival in the U.S. in 1829 that first introduced many Americans to Asia and Thailand. “Early on, it was the twins shaping the way Americans thought about Asia,” Orser says. Later in the Bunkers’ lives, he explains, the opposite was true: The growing number of Asians in the U.S. shaped how other Americans viewed the Bunkers. By that time, the twins themselves had married (their wives were sisters) and eventually fathered 21 children between them during a time when interracial marriage was taboo. However “normal” and domestic the twins’ lives became, however, they were often viewed with curiosity and disdain as “monstrous” or subhuman.

“The twins’ ‘monstrous’ characteristics were nothing but projections cast upon them of American fears, evidence of the public’s recognition that American society had its own monstrously ambivalent qualities,” including slavery and the sectionalism that led to the Civil War, Orser writes.

Indirectly, Orser’s interest in Chang and Eng grew out of his own background: Orser’s mother is Thai, and he spent part of his young adulthood studying, teaching, and working in Thailand. The book began as Orser’s doctoral dissertation at Ohio State University, and was published by the University of North Carolina Press in November. Since then, it has received international attention, including being the subject of articles in the New York Post and Britain’s Daily Mail. (Both reports focus in part on one of the most titillating aspects of the twins’ story: their sex lives.)

Orser says the popular biographies and novels written about the twins fall short of accuracy because they – unsuccessfully, in his view – try to get inside the twins’ heads. “Those (books) were grounded in stereotypes of what we think conjoined brothers would be like and what we think Asian-Americans would be like,” he said. The difficulty in giving the twins a voice is the lack of recorded statements by Chang and Eng about themselves: Plenty was written about them during their lifetimes, but very little by them – and nothing about their interior lives.

Nonetheless, Orser has been able to draw some conclusions about the twins’ as individuals. “They’re extremely bright, and they’re able to read social circumstances very well,” he says. These talents – honed by a career chatting with curiosity seekers who paid 50 cents for the privilege of meeting the twins – helped Chang and Eng gain the social standing necessary to establish themselves as country gentlemen in 1840s North Carolina, a time and place where nonwhites were bought and sold as slaves. However, Orser notes, Southern racial attitudes were governed by the black-white divide: “Asians don’t fit into the racial landscape they’re settling in, so they can create a space for themselves,” Orser says.

And for the Bunkers, settling into that niche meant owning slaves – even though they themselves were racial minorities and early in their lives grew angry at accusations their mother had “sold” them to an American promoter. “It is ironic, especially for us, but in other ways it was completely understandable,” Orser says of the brother’s status as slaveholders.

While the brothers outlived the institution of slavery – they died within hours of each other in 1874 at age 62 – their own amazing life stories have outlived them. Orser’s academically rigorously but accessible biography can help 21st century readers connect with these two men and what their lives tell us about 19th century America.

While the brothers outlived the institution of slavery – they died within hours of each other in 1874 at age 62 – their own amazing life stories have outlived them. Orser’s academically rigorously but accessible biography can help 21st century readers connect with these two men and what their lives tell us about 19th century America.

The Lives of Chang and Eng by Joseph Orser is available via Amazon.com and other retailers.