Closing the Book

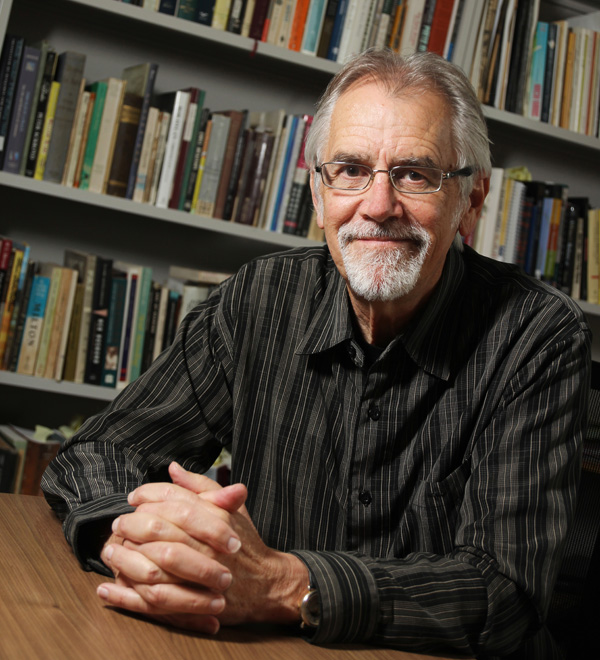

UWEC’s Max Garland reflects on his term as state’s poet laureate

Tom Giffey, photos by Andrea Paulseth |

as Wisconsin's poet laureate.

Max Garland may have taught thousands of Wisconsinites about the power of verse during his soon-to-conclude two-year tenure as the state’s poet laureate, but for him the experience has been an extended lesson in geography. Since taking the post on Jan. 1, 2013, Garland has put 19,000 miles on his vehicle crisscrossing the state’s communities, large and small, to make more than 90 public appearances to promote the literary arts. (One of his last will be a reading at 7pm on Thursday, Nov. 20, at the L.E. Phillips Memorial Public Library in Eau Claire.) As heartened as Garland has been about Wisconsinites’ hunger for poetry, he has been disheartened by what he terms a “remarkable lack of understanding of, and support for the arts” by the state’s elected leaders. We asked Garland to reflect on his term as poet laureate, and he opened up about his expansive definition of poetry, why older people are more drawn to verse, and the importance of tire rotation for traveling bards.

~

"We encounter poetry long before we know it’s poetry – it flourished in Wisconsin long before there was a Wisconsin. More of us have poetry stashed away in our heads and hearts than readily admit it."

~

Volume One: What do you know now about the state that you didn’t know before becoming poet laureate?

Max Garland: I’ve learned to properly pronounce Mukwanago and Oconomowoc, and that much of the state still can’t pronounce Eau Claire, or keep it separate from La Crosse. Also, I’ve learned that the school mascot in Tomahawk is the hatchet, which seems slightly redundant.

What have you learned about the state of poetry?

That we encounter poetry long before we know it’s poetry, and that it flourished in Wisconsin long before there was a Wisconsin. And also that more of us have poetry stashed away in our heads and hearts than readily admit it.

Poetry is one of the most ancient of arts. Why is it still relevant?

The greater the quantity of blatantly disposable language and imagery beamed at us from iPhones, desktops, and plasma screens, the more essential a deeper, truer, more reflective and compassionate language becomes.

You’ve done about 90 public events as poet laureate. What kind of settings have you spoken in?

Grade school cafeterias, high school classrooms, bookstores, public libraries, city halls, senior centers, a church, a tent, a theater built by Frank Lloyd Wright, a street corner in Sheboygan, and an old paper mill.

Do you have a standard presentation? What kind of points do you try to make to your audience?

I try to adjust to the place and approximate age and height of the audience.

Is the public receptive to what you have to say?

It’s surprising how many people, no matter where you go, have things they long to express, or long to hear expressed. Also, it’s surprising how many people hope some of their best words survive, words that more deeply testify to what they thought and felt while on earth.

Three years ago, Gov. Scott Walker cut funding for the poet laureate program out of the state budget. How have you been paid – or at least compensated for your mileage?

The governor has shown a remarkable lack of understanding of, and support for the arts (and public education) in our state. Fortunately, others have stepped up, such as the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences Arts and Letters, and the Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets, just to name a couple of non-profit organizations. They’ve pitched in to provide a travel budget. Also, many places I’ve visited (schools, libraries) have provided expenses, lodging, and small honorariums. After a reading last night, for instance, I slept in a spare bedroom about 90 miles from here.

Given that the position survived despite the state budget cut, can you make an argument for it being an official state-funded post again?

State support signals that we understand the need for balance between economic and cultural needs, care about nourishing creativity, and want our most articulate and imaginative young people to feel welcome here. If you happen to live in an affluent community, or a place where private support for the arts is strong, that’s fine. But many (and many children) in Wisconsin are not so lucky; that’s where state support is most important.

~

"We have people in Eau Claire doing amazing things to see that art and culture flourish here. However, the fact that Wisconsin ranks 48th in the nation in per capita arts support, while we live next to the state that ranks first (at 44 times our level), is not a persuasive argument for keeping the best and brightest here."

~

What’s your opinion on arts funding in general in Wisconsin? As you’ve pointed out during your tenure, Wisconsin lags far behind its neighbors, especially Minnesota, in terms of per capita arts funding. How does this impact artists and artists-to-be?

We have people in Eau Claire doing amazing things to see that art and culture flourish here. However, the fact that Wisconsin ranks 48th in the nation in per capita arts support, while we live next to the state that ranks first (at 44 times our level), is not a persuasive argument for keeping the best and brightest here.

How does Wisconsin’s relatively low arts spending impact the state’s economy as a whole?

Since state arts support in Wisconsin is currently tied to tourism (the Arts Board is under the jurisdiction of the Department of Tourism), arts groups are often persuaded to initiate projects, not based on their inherent or lasting value, but on how many tourist dollars can be diverted from one Wisconsin community to another.

You’ve said that older people seem very interested in experiencing poetry, both as listeners and writers. Why do you think that is?

Age lends urgency to the universal need to say what you think, who you are, what you fear and love, while there’s still time and light enough to say it.

That being said, what can be done to get younger people interested in poetry and other literary arts?

It helps if we think of poetry in an expansive way – not excluding rap, hip-hop, song, slam, hymns, chants, religious texts, as well as those hefty anthologies of beautiful words our elders have left for us. Less political ambition and greed and more understanding on behalf of our elected leaders of the value of early encouragement in the arts and poetry would help. The more you love words and learn to utilize the inherent power of language, the better you’re likely to do in school, and beyond. The more you read, the more you understand your connection to others (human and non-human), and the more your own powers of expression and capacity for wonder are ignited.

Has all the traveling you’ve done inspired your own creativity? Could you, for example, write a poem composed entirely of Wisconsin place names?

Sure, if I could use the names of rivers, too. There’s the Killsnake River, Scuppernong River, Rat River, Potato River, Onion River, and my personal favorites – the Tomorrow River and the Embarrass River. I’m actually embarrassed to say how many times I’ve crossed the Tomorrow River.

What will you miss about being poet laureate?

I’ll miss the opportunity to make the case for the creative imagination as a vital part of who we are, or at least making the case as often.

What won’t you miss?

I won’t miss navigating the never-ending Wisconsin road construction projects, the maze of detours, many of which have bewildered my car’s GPS device.

What advice do you have for your successor?

Rotate your tires. Learn to pronounce Eau Claire (which is different from La Crosse). And remember that poetry is too important to be left to professionals.