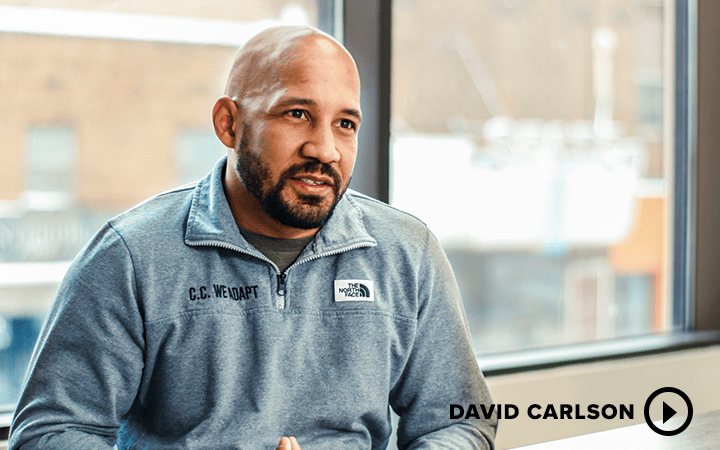

David Carlson never thought he’d be a businessman, but now he co-owns several businesses. He never thought he’d be an attorney, but he’s poised to graduate law school later this year. He never thought he’d be a dad, but now he’s a married father of three.

Yet there are even more basic milestones his younger self couldn’t comprehend.

“I never thought that I’d live past 20, and I never thought that I’d live past 30,” he reflects. “So I’m in all new territory, and every second is a blessing.”

Carlson’s life is a testament to the power of mentorship and personal growth. He spent his early years in uncertain, violent circumstances. As a homeless teen in Minneapolis, he committed burglaries, carried guns, got into fights, and ran from the police. After time in juvenile detention, he was adopted by a family in Rice Lake. While he was one of the few Black kids in town, he says the community largely accepted him. At age 19, he served in Iraq with the Wisconsin Army National Guard; he was deployed again a few years later.

By age 25, he was out of the military, but his life was on the rocks: “My entire life has been violence, abuse, trauma,” he says. “And I kind of just broke, and it was a downward spiral.”

While mixed martial arts and boxing brought a bit of stability to his life, Carlson said, “When I wasn’t actively competing, I was drinking and doing drugs, trying to put myself in a coffin because I couldn’t deal with the emotions and stuff that I felt, and all of that was based on a perspective.”

Locked up for burglary, Carlson began to give in to the perspective that he was a criminal. He became more violent and got into fights behind bars, ending up in solitary confinement in the Eau Claire County Jail. Carlson hated the bully he’d become, and came to an epiphany: No matter what others told him or how they treated him, it was up to him to choose to be the person he wanted to be.

“In solitary confinement, I was either going to end my life or I was done (causing harm) — and I sat on that decision for three days,” he recalls.

“That’s when I decided to change,” he continues, “but I think it took all of the experiences I had up until 31 or 32 years old for it to click that I had control over my perception — who I was.”

The epiphany came in part because of the mentorship of Michael Orban, a veteran of the Vietnam War who has spent years working with other veterans who dealt with combat-related PTSD.

“I’m in all new territory, and every second is a blessing”

Drawing on his past interest in physical fitness, Carlson doubled down on working out — doing hundreds of burpees and pull-ups in his cell — and delved into writing and reading. After leaving prison for the last time, Carlson entered the world of CrossFit — becoming a fitness trainer — while also pursuing a degree at UW-Eau Claire, where he graduated in 2019.

A subsequent job as an organizer for the ACLU of Wisconsin taught him about social issues in the Chippewa Valley, and he yearned to get more directly involved with individuals. “There wasn’t a solution that was being presented to the youth and adults in this area that resembled my background, so I decided that I needed to be the person that did that,” he says.

Carlson started as a solo provider of peer support services, eventually forming a business, C.C. We Adapt. Today, that business has dozens of provider and mentors and contracts with departments of health services in 28 Wisconsin counties, offering Medicaid-reimbursed peer support services. Like Carlson, most of the providers have personal experience with issues such as substance abuse, mental health, and incarceration.

Much of that support comes in the form of physical activity — a legacy of another of Carlson’s mentors: a fitness coach he had during his time in a juvenile detention center in Hennepin County, Minnesota. Though he was a middle-aged white man, the coach was able to connect with a group of mostly Black and brown juveniles by demonstrating his weight-lifting prowess. “That communicated to us that he understood our value for making sure that we were strong enough to protect ourselves,” Carlson said. “Because he did that, that also gave him the ability to also speak to us and give us lessons in other areas of life.”

Likewise, Carlson and his colleagues at C.C. We Adapt use physical activity — whether it’s working out in a gym or rock climbing — to meet clients where they are and help them improve their lives. Taking youths on excursions, such as trips to the Boundary Waters, teaches them to use coping mechanisms to overcome stressful situations. “Your brain and your body can’t distinguish that stress from when you’re in school and you get dysregulated,” Carlson says.

As the name of the business suggests, the idea of adaptation is key: Just as increasing the amount of weight you lift improves physical fitness, positive mental health interventions — like physical activity or learning a coping skill — bring about mental adaptation, he says.

In addition to overseeing C.C. We Adapt, Carlson is also co-founder of Next Generation Properties, an affordable housing business, and Next Generation Mentors, which provides tenant support mentorship.

On top of all this, Carlson is also pursuing a law degree from the Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul. In a little over a semester, Carlson expects to receive his degree with a primary objective of working in health law compliance. Healthcare is a heavily regulated industry, he says, and businesses tend to be conservative. But Carlson says there is plenty of gray area in the law that could allow for more creative treatment options under Medicaid reimbursement.

“I just realized that knowledge of law — as far as coming from the background of being an activist or an advocate — is paramount,” he said.