The first thing Pa Thao remembers about stepping foot in Eau Claire at the Chippewa Valley Airport was the icy breeze tickling her nose, and the snow surrounding her on the freezing December day — her first interaction with Wisconsin winters.

Born in the Bon Vinai Refugee Camp in Thailand, Thao was no stranger to turbulence, as her family frequently fled to various refugee camps before they sought a new life in the United States.

New to Eau Claire, 12-year-old Thao learned not only how to advocate for herself, but to advocate for her family, as she was often asked to interpret for her mother. “I didn’t know English really well in order to interpret for her,” Thao said. “But it was either me or nothing. … I always see that as a form of injustice — to not have language be accessible, to not have programming be accessible, because you don’t speak that language. And I always struggle with that, even today.”

The Eau Claire Area Hmong Mutual Assistance Association, she said, was the light at the end of a tunnel. There, her family connected with family and friends — as well as other Hmong individuals in similar situations — who helped her mother find work and her family find a sense of community.

After graduating from high school, Thao initially pursued fashion design at UW-Stout, but — after taking a year off to help her sister at a family restaurant in Michigan — she changed gears to pursue social work. Her first job was at a residential program helping young women struggling with alcoholism and addiction. A few months later, the perfect position came available at the Hmong Mutual Assistance Association, connecting low-skill workers with employment — something the association had done for her family. “Things just happen for various reasons,” Thao reflected, “and the universe puts everything together, and you’re meant to be where you are.”

“I always see that as a form of injustice — to not have language be accessible, to not have programming be accessible because you don’t speak that language.”

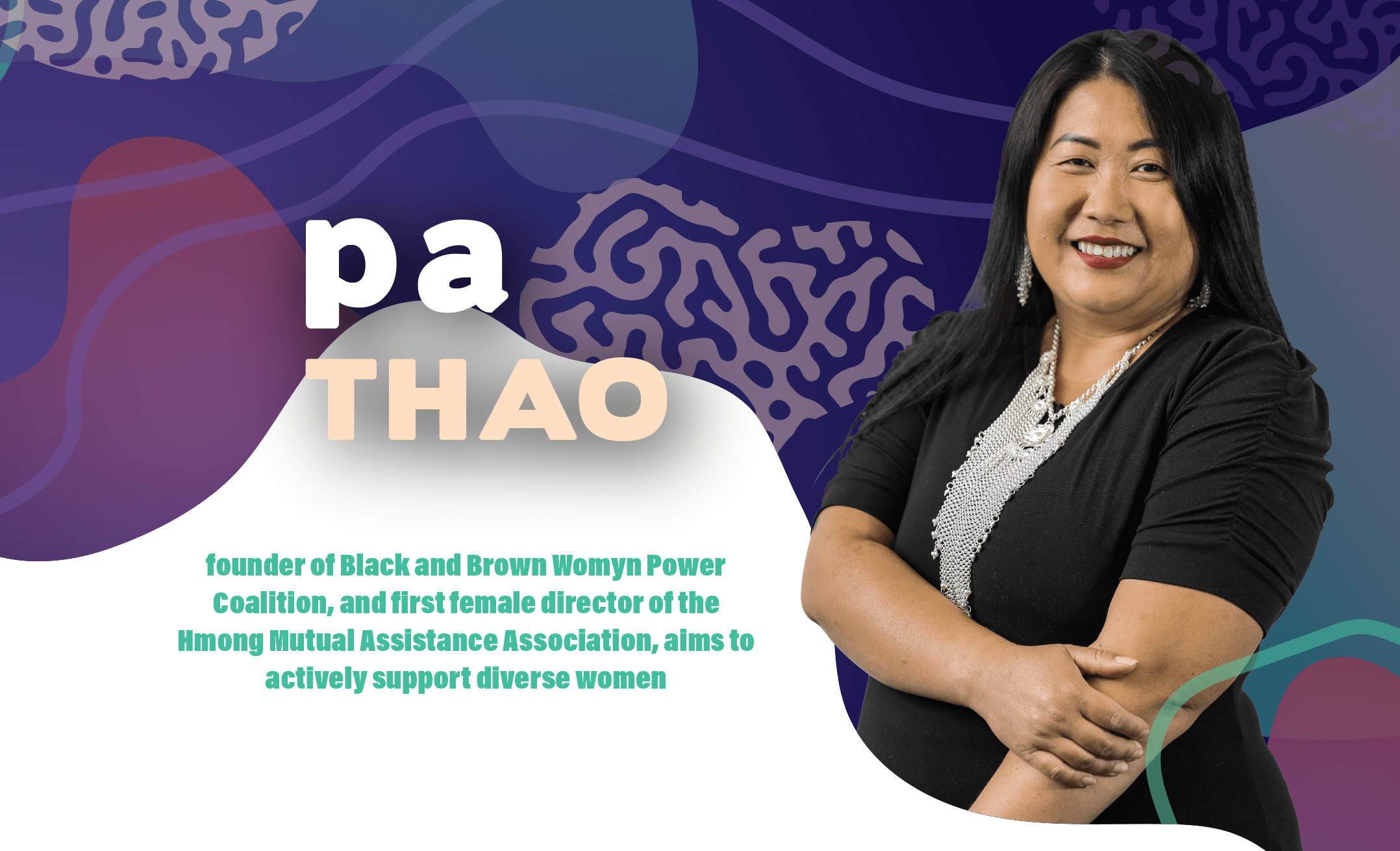

So in 2010, she knew it was a sign that the position of director at the association was vacant, and she applied. As a typically shy and introverted individual, Thao was terrified to interview in front of a dozen board members and community representatives, and even more daunted by the prospect of being a leader. But the universe was watching out for her, she said, because she got the job.

Immediately, she was met with resistance, as she was the first Hmong woman to hold the position in the association’s history — and she was also an unmarried single mother, something that many traditional Hmong individuals resented. And she had a progressive agenda. The organization didn’t have a budget, a strategic plan. Most departments were led by men, and she found the work environment to be inhospitable to women and mothers, not offering maternity leave or flexibility to bring children into work. “It was a lot stacked against me,” she said.

Yet, In her years working as director of the Hmong Mutual Assistance Association, she raised funding for the domestic violence department from $60,000 to $180,000 annually, hired more women leaders, added a strategic plan and budget, and worked to make the organization as sustainable as possible. Once she felt she could no longer contribute her skills to the organization, she knew she needed something new.

That’s when she founded the Black and Brown Womyn Power Coalition, a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping women with issues of sexual assault and domestic violence in an effort to start conversations about intercultural domestic violence and sexual assault to erase its stigma.

“I want to make sure anyone that is in that kind of situation can call,” she said, “whether they speak Hmong or whether they just need someone who is on the phone with them to provide support for them as they are walking through that door.”

Thao is now locally and regionally recognized as a champion for women, children, and families in the Chippewa Valley, but advocating for change wasn’t easy for Thao. “I’m an introvert,” she admitted. “I have an anxiety of socializing with strangers. I really do. I have to really put myself out there. … You won’t know it, but I hate it. But I do it because I have to.”