I’m probably in the sky, flying with the fishes. Or maybe in the ocean, swimming with the pigeons. See, my world is different.

The lyrics of the Lil’ Wayne song “Sky’s the Limit,” blared through the communications box of David Carlson’s convoy vehicle, only seconds before it tumbled over an underground improvised explosive device (IED), lighting his vehicle on fire.

It was 2008, during his second tour of duty in Iraq, and he knew from his years of training that if he stopped his vehicle, he’d lock the rest of his convoy in a choke position — perfect for a deadly secondary ambush. Blazing fire, he continued driving.

This was one of many moments in Carlson’s life that are illustrative of how he sparked prolific change from trauma. At first, the scene seems perfectly ordinary: blaring a 2000s rap song through a car radio with a coupla’ pals.

But, Carlson’s life was marked by moments like that — the juxtaposition of trauma and the potential for normalcy. Moments like that — combined with his selfless personality and his insatiable desire for justice — led him to found We Adapt, a new organization dedicated to inclusive peer support and mentorship in the areas of public health and social services; to advocate as regional organizer for the ACLU of Wisconsin; and to pursue a law degree to ensure no one goes through the same experiences he did.

When Carlson was only 10 years old, a police officer aimed a gun at his head — a consequence for a crime he did not commit. His strained relationship with law enforcement only escalated, beginning first with school suspension, followed by expulsion, juvenile detention, and electronic monitoring. He moved rapidly through group homes.

“People outwardly talk about what they see in the city, call us animals, basically say we don’t have morals,” Carlson said. “We’re animals, they say. And that’s who I was. I was the group of people they described. So to me, I accepted that at that time. I am what they say, even though I don’t feel like it. Because they’re not going through the shit I’m going through. They’re not running from the cops, sleeping in basements. … I just had a lot of self-loathing. I just had hate in myself.”

That’s when he decided to pursue the military.

The structure of the military was something he had been craving his entire life, he admitted, and he thrived with the hard work required to be in the National Guard. But — like so many who go to war — he returned to the U.S. traumatized by what he had seen. That’s when his struggle with alcoholism spiraled.

“They call it passively suicidal,” he said. “I was always doing things looking for that end.”

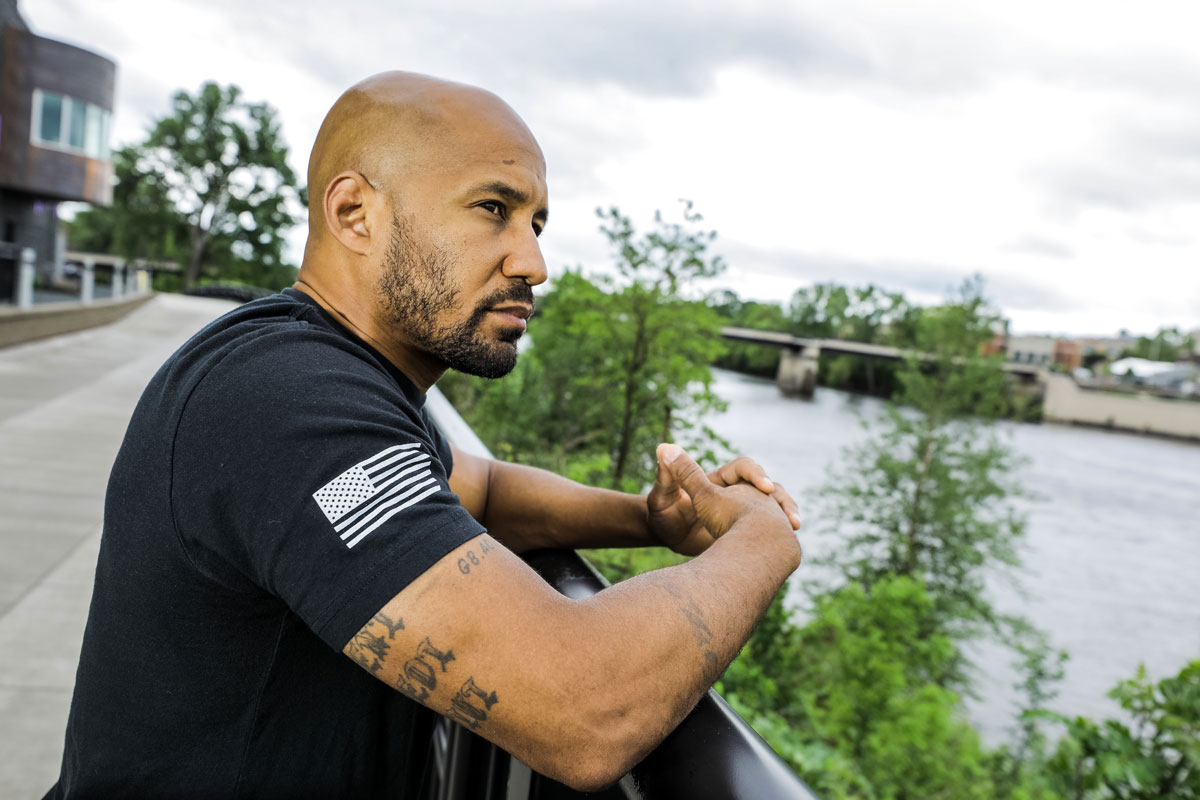

A pivotal moment, Carlson said, was when he was chased down by the Eau Claire Police Department at the lot where the Pablo Center at the Confluence is now located. Afterwards, he faced 15 years in prison, and that’s when his life came to a crossroads: either he would continue on his path of violence, or he’d change his life completely.

So, he decided he would change.

“I was the group of people they described. So to me, I accepted that at that time. I am what they say, even though I don’t feel like it.”

Once released, Carlson joined a local CrossFit gym in Eau Claire. He fell in love with the sport and the community — which includes many veterans — and so he joined the CrossFit organization Next Objective, which supports veterans.

From there, he joined Ex-Incarcerated People Organizing (EXPO) as a volunteer, finished his creative writing degree at UW-Eau Claire (with a certificate in legal studies to boot), was hired by Milkweed — a peer support organization — and, ultimately, went to work for the ACLU of Wisconsin. Carlson had finally found his purpose: helping others.

At his newest venture, We Adapt, he aims to connect peer supporters to children to ensure their traumatic experiences are validated and understood. “It will be providers who have been marginalized,” he said, “homeless, who have had to sleep in basements, who have had to eat trash, who have gone hungry, who know what it’s like to starve.”

Carlson is currently applying to law school, to continue his knowledgeable advocacy work.

“One piece, the ultimate goal, is to do no harm,” he said. “That is a fact. That is a moral that — no matter what culture you come from — that is what you should strive for.”