A Box of Clues

on a historical hunt, books uncovered, records spun, and a resurrection gone awry

BJ Hollars, photos by BJ Hollars |

Let me tell you how I first met Fannie Ingram Schwahn. How I was browsing the local antique store a few summers back when there, buried amid the flotsam and jetsam, I came upon a wedding certificate dated June 5, 1922. Fannie was listed as the bride, and though I knew nothing of her – had never even heard her name – I was entranced, nonetheless by her story. Or rather, the story of how her marriage certificate had made its ways into my hands.

It was a story, I assumed, that likely involved Fannie’s death, the subsequent cleaning/sorting/distributing of her earthly possessions, and a decision by somebody somewhere that there was some monetary value in a dusty old marriage certificate. It turns out there was– $2, in fact – which I gladly forked over in order to learn something of far greater value.

Who was Fannie Ingram Schwan? I wondered. And how far might I trace her story?

What began as a hypothetical question soon took root in reality: Fannie became my research project, my experiment, my mystery – one I would dedicate the rest of the summer to solving.

I began by reading every mention of Fannie in the local paper, and when that trail ran cold, I visited her grave, her former homes, and finally – in some gift from the gods – uncovered her wedding dress in the Chippewa Valley Museum archives. That summer, I felt as close to Fannie as I did anyone, and in an effort to prove it, I tracked down her wedding photo, framed it, then placed it in our dining room alongside the family photos.

“Is that your grandmother?” dinner guests would ask.

“Nah,” I’d say, “just some woman I never knew.”

Of course, I wanted to know Fannie better – desperately – but the clues could only lead me so far. A year came and went, and though the clues to Fannie’s life had long since faded, I still found myself talking about her. One night, while speaking before a crowd at a fundraising dinner, I managed to work Fannie into my remarks. Minutes later, at the dinner’s conclusion, a woman named Jill bee-lined toward me.

“I have Fannie’s books,” she said. “Her records. Everything.”

“But … how?” I asked.

Jill explained how she’d been helping a friend host an estate sale at Fannie’s former home, and to pass the time, had begun perusing the woman’s books.

“Fannie fascinated me,” Jill said. “And while everyone else at the estate sale walked away with the big items – her fancy dining room table, or her expensive Persian rug – no one saw the value in her records and books.”

As the sale wound down, and when it was clear to Jill that most of the books and records would soon end up in the dump, she gathered as much as she could and placed the items in her car.

“I couldn’t bear to have it all thrown away,” she said. “It was like … like I knew someone was going to want this stuff one day.”

Eyes wide, I whispered, “You found him.”

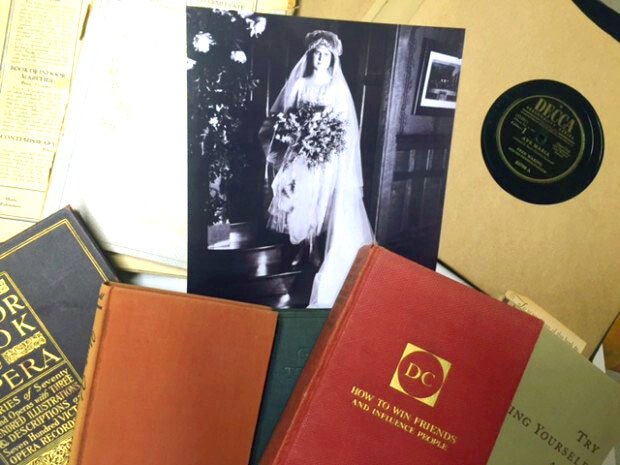

A few weeks later, after Jill and I spent an afternoon trying to figure out Fannie, she sent me home with a storage bin overflowing with the woman’s belongings. Inside were two dozen or so books (The Victor Book of the Opera, How To Win Friends and Influence People, Your Key To Happiness, The Practice of the Presence of God, among others) as well as several dozen sleeves of records (Songs of Devotion, The Heart of the Piano Concerto, South Pacific, Hukilau Hulas).

I drove the bin home (“What’s in there?” my wife asked, “No time!” I replied), then hunkered down in the unfinished section of my basement to begin my analysis.

I closed the door, reached for the records, and tried to bring Fannie back.

Each record was a clue, I decided, and one after another, I blew the dust from old, 10-inch 78s and placed the needle on one shellac plate after the other. I tried to imagine the last time these records were spun, and the last ears to have heard the music that resulted.

As the songs wafted from my speakers, I turned my attention to her books, flipping through the brittle pages in search of clues in her bookplates, her dog-eared pages, her newspaper clippings pressed as gently as butterflies. I found a few ticket stubs, some Christmas cards, and a postcard of a male nude. Pressed inside The Love Letters of Abelard and Heloise I discovered a poem (“I Said A Prayer For You Today”), and tucked inside Parliamentary Law, a handwritten page with notes on feudalism, the papacy, and Ireland.

Finally, at the bottom of the bin, I found a mostly unused agenda book. Stuck inside the page marked Nov. 3 was a three-by-two inch card with an angel on the front. In its interior, a short message written in script:

Such a small card to carry so much love.–Gail

Who’s Gail? I wondered. And is Gail the key to understanding Fannie?

She’s not, of course – at least not any more than any other clue I’ve cobbled together. Yet this hardly keeps me from returning once more to the pages of all those books, searching for some scrawl, some annotation, that might bring Fannie into sharper focus. Some time around midnight – after all those pages flipped and all those records spun – I realized I was doing it again: piecing together a life with a few glimpses at my disposal. It wasn’t the first time I’d tried to create a true account of a stranger, and it probably wouldn’t be the last.

The problem, of course, is that it’s impossible to write a true account of anyone’s life – especially when all that remains are the random assortment of details. What we do with the details – the story we make from them – can hardly be considered truth. When I first found Fannie’s marriage certificate, some part of me hoped that her story might be spun as simply as a record, one already etched and only in need of a needle. I wanted to be that needle, but I wasn’t. How could I ever be given all I’d never know?

It was getting late, but not so late that I didn’t spin one of Fannie’s records one last time before returning it to its sleeve. Through all the clicks and crackles, I closed my eyes and listened hard for clues.

This time, though, all I heard was music.

For more on Fannie, read B.J. Hollars’s previous piece, “Finding Fannie,” in the Feb. 4, 2015, issue of Volume One. This piece was previously published in slightly different form in Michigan Quarterly Review.