At the Northwest Reading Clinic, Ruth Harris has brought 50 years of life-changing gifts to the Chippewa Valley.

words by Lauren Fisher

photos by Andrea Paulseth

A good teacher must be patient, flexible, and empathetic. She is interested in the material and understanding of how her students learn. Kindness is essential. But what is it that marks the difference between a good teacher and one who serves for 50 years, helping more than 5,000 students overcome personal, emotional, and physical difficulties to improve their literacy and lives? For Ruth Harris, who has operated the Northwest Reading Clinic in Eau Claire since 1986 and has taught there since its inception in 1969, the difference was having a bad teacher.

“She should never have been a teacher,” Harris said. “I don’t think she really liked kids.” Harris describes her second-grade teacher as a drill sergeant — in fact, the woman was a former Army sergeant. She inspected each child before class and made sure their shoes were shined perfectly and their teeth were clean. Then she would open each student’s pencil case. If any pencils had erasers, she would cut them off and throw them away.

“We don’t make mistakes in here,” Harris recalls the woman saying. This was a trial for Harris, who was uncomfortable sitting at her desk as her teacher instructed — she demonstrated the posture as she told the story, placing her feet flat on the floor, shoulders back, hands clasped together on the desk — due to the effects of a case of polio she survived earlier in her childhood. The pressure of required perfection drove Harris to throw up before school every morning.

One day on her way to class, a gust of wind swept dirt onto her shoes. If Harris used her handkerchief to tidy them, the cloth would be dirty, and the teacher would surely rap her knuckles for the infraction! She ran home in tears.

It was the good fortune of the class that Harris’s parents, and other parents, took the children at their word for the teacher’s behavior, and the woman was replaced by the following Monday.

“Someday, I’m going to be a teacher,” Harris recalled thinking. “And I’m not going to do that. … That’s what got me through being able to go to school every day, is thinking how I would do things differently, and how a teacher could affect kids so deeply.”

She had learned everything she wouldn’t do from that second-grade teacher. From then on, she paid close attention to her instructors, searching for successful techniques, neat approaches, and methods she could incorporate into her own style to be a successful educator.

Years later, Harris had done a stint of teaching fourth-grade, returned to school to get a master’s degree in reading — she has since attained two more in learning disabilities and emotional disturbance — and set out to help students with reading problems reach their potential. In her experience, students who were not reading at their designated grade level were classified as “naughty” and sent to a “glorified boiler room” office for remedial reading. Harris wanted more.

The Milwaukee Journal classified ad read: “Help wanted Male or Female — Well-known psychiatric clinic is looking for somebody to work in a psycho-educational setting.”

While Harris had never heard of Eau Claire, she was intrigued by the posting.

They had patients with learning problems that could not be psychoanalyzed or medicated away: They needed a teacher.

Harris was put in charge of the operation. Her first move was to rename the institution: “Northwest Reading Clinic” was much friendlier than “Psychoeducational clinic.”

Friendliness — hominess — has been a priority for Harris since she opened the clinic, which is at 2600 Stein Blvd. in Eau Claire. The offices are furnished with oversized leather sofas and the walls are barely visible behind student artwork, prints, crafts, a curio full of figurines, and bookshelves full of texts. Facing the front door is a tribute to her family’s education and teaching, featuring framed diplomas, degrees, and Eau Claire Leader-Telegram articles about her mother’s time as a foster grandparent and Harris’s own work with the Reading Clinic. In the room where she holds her sessions, a cork board is plastered with portraits and notes from her current and former students.

Harris instructs all of her young students to bring a “get-to-know-you box” to their first appointment, full of objects that explain who they are. It’s a way to establish rapport with people and start off on the right foot. Most prized in that box is a snuggle-sized, curly-furred gray therapy poodle named Monet. Even the most macho of high school boys warm up quickly when they get a chance to greet the little guy, Harris said.

Harris and the other teachers at the Northwest Reading Clinic, Sandy Ballin, Kerrie Jordan, and Kay Bjork, met in Osseo for an annual get-together in January.

The Northwest Reading Clinic serves people of all ages — Harris currently works with individuals between the ages of 4 and 66 at all educational levels and proficiencies. The clinic’s services range from basic reading and mathematical literacy instruction to G.E.D., ACT, and SAT test preparation, including ADD coaching, study skills, time management, organization, and more. Before instruction begins, each student is given an initial diagnostic evaluation by a licensed psychologist, and many have their sight and hearing tested to identify physical barriers to learning. Instructors develop individualized education plans for every student, with a focus on fostering student independence.

“There’s two secret sauces,” Harris said. “One is that it’s one-on-one, and that I’m not part of a curriculum where I have to do a certain method. I can mix and match and individualize to each student. No two have the same program.” The other special ingredient, she says, is Monet.

Many students come to Harris during difficult times. Academic struggles, be they instigated by learning disabilities, environmental factors, or high expectations on the part of students or their guardians, can have an emotional toll on a person, their activities, and their relationships. Many bright people believe that they aren’t smart when they don’t learn at the pace expected by society, or develop a resistance to the subject material, Harris said.

If these problems are not addressed, they become lifelong hardships. Teenagers and adults develop tricks to navigate the world without reading and writing, such as wearing an elastic bandage to feign a wrist injury, then asking others to fill out forms for them. Others rely on family members to help them with reading and writing, using exceptional memories to relay information for transcription. Many of these people hold important positions or even run their own businesses, Harris said. But sooner or later, it comes to light that they need help.

ALL BECAUSE OF RUTH

Renee Bodenschatz, 31, of the Twin Cities, has a talent for memorization. She honed it in elementary and junior high school as a way to avoid reading out loud in class. When her teachers instructed the class to take turns reading paragraphs out loud, Bodenschatz would count how many students were queued before her, find the paragraph she would need to read, and practice it silently until it was her turn. Then, she would recite it from memory rather than sight reading.

“It was very hard for me at that time to understand what I was reading when I was reading out loud,” Bodenschatz said. “I was so focused on each word, I couldn’t pay attention to the big picture.” But because of her problem-solving and talents in other subjects, her struggle to read and write went unnoticed.

“When I found out that I was dyslexic, I started to cry because I was so happy that it had a name,” Bodenschatz said. Her mother had her tested in seventh grade at the recommendation of a cousin who was studying learning disabilities in college. Shortly after that, her family began making the drive from Rice Lake every Saturday for tutoring sessions with Harris.

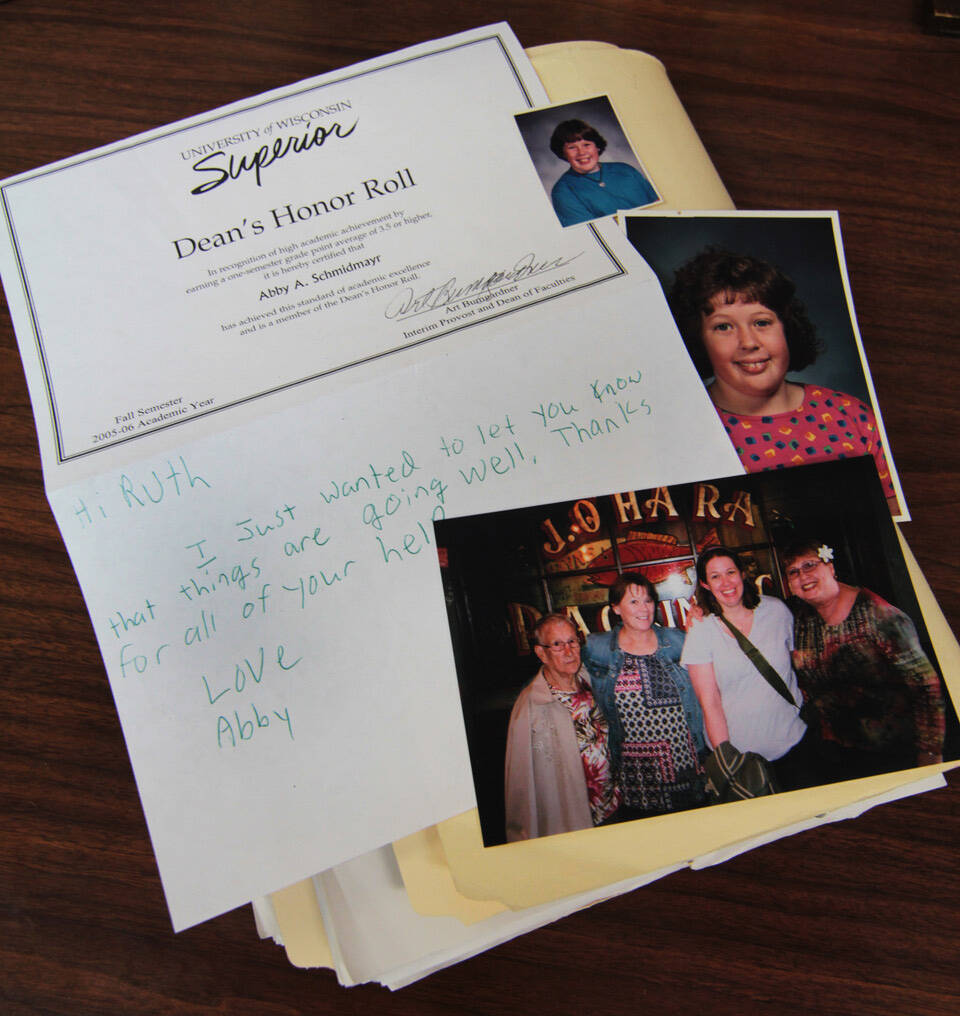

When Abby (Schmidmayr) Bober was in elementary school, her teachers would push her to do her assignments: “You’re so smart, why don’t you just sit down and do it?”

“I hated reading,” she said. “It was always something we struggled with before Ruth.” Bober was diagnosed with ADD when she was eight years old. It was a two-and-a-half hour drive from her home in Phillips, Wisconsin, to attend tutoring sessions with Harris every two weeks.

Before her diagnoses, Bober dreaded going to school. She would count the years remaining until she no longer had to attend. But one-on-one sessions with Harris were a different experience. They were affirming, instructional, but also friendly and loving. “It never seemed like school to me,” Bober said. She looked forward to each session, and with help from Harris, eventually she looked forward to reading. When her mother came in one night to turn Bober’s light off, she begged for a few more minutes to read, and both knew that Harris had changed the girl’s life.

The pair shared a love of animals — Bober’s get-to-know-you box contained a toy cat that would “give birth” to a litter of kittens. Now 35, she works as a veterinary technician in Minnesota. “I would never have become that,” Bober said. “I probably wouldn’t have even gone to college after high school if I hadn’t went to Ruth.”

“I don’t even want to know what it would be like,” Bodenschatz said, trying to imagine her life without Harris. She would never have gone to college, or found her career in social services without Harris’s help, she said.

“It was kind of like taking this puzzle that was jammed together but didn’t really make a picture,” Bodenschatz said. “She helped me take apart that puzzle and repuzzle it correctly.”

Pieces of Bodenschatz’s puzzle included test-taking skills such as reviewing reading questions before reading the assigned material, so that she could keep an eye out for relevant information. Bober’s puzzle came together when they practiced organizational skills. But no matter who she is working with, and no matter what academic subject they are facing, Harris is always teaching her students about the strength that lies in their individuality.

“She looks at you as an individual, sees your individual qualities, always looking at the positives, always congratulating you for things you’re doing right, not focusing first on what you’re doing wrong,” Bodenschatz said.

“She has helped me overcome so much to be able to build the confidence in myself that she always saw in me,” she said, her voice rising and catching in her throat.

Robert requested the use of a pseudonym to avoid facing the negative stigma associated with his own diagnoses of dyslexia and ADD. He got his first taste of the prejudice some people have against those with learning disabilities in junior high school when he was placed in specially tailored classes in the ’90s. “Some kids would call it the ‘retard’ class,” he explained. “As an adult I have concealed my disability because I know how it could influence folks’ thoughts about myself and my ability to climb the corporate ladder. Whether they admit it or not, once you’re known for something like that, it is not easily forgotten.”

Robert’s mother, Shelly (also a pseudonym), struggled to find help for Robert in elementary and junior high school. She saw that it took much longer for Robert to complete assignments than other children, but when she went to the school for support, his teachers were dismissive.

“For many, many years we would go in and teachers would say, ‘Oh that’s normal for boys,’ “ she said. But when Robert reached high school Shelly knew she needed to find the right support for him or risk his ability to go to college or get a good job.

“I didn’t seem to be getting any help with the school district, so that’s why I went to Ruth,” she said. Harris connected them with a doctor who diagnosed Robert with dyslexia and ADD.

“I remember sitting in a session with Ruth and my son, and she was bringing up all kinds of people who had these diagnoses.” Ruth told Robert that great minds and leaders had dyslexia, including Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, and perhaps Presidents Kennedy and Washington. “We’re gonna take these because these are gifts, and we’re gonna learn how to use it,” she remembers Ruth saying. “It was a whole new way of thinking about something that doesn’t work in the school system, but works really well in real life,” Shelly said.

“She taught me that I was smart, I just learn much differently than the majority of folks,” Robert said. “My brain works more quickly, I have the ability to assess presented information, evaluated it, and make the most logical decision before others finish contemplating. This way of thinking was fostered by Mrs. Harris.” Robert has since graduated college and become an engineering and construction coordinator for projects in western Wisconsin.

MAKING THE CALL

For the people who receive a diagnosis later in life, seeking help can be more challenging. There are fewer resources for adults with learning disabilities or who did not have a chance to learn to read, and some people can be afraid to come forward and ask for help. In some cases, adults will consider making a call to the clinic to get help for two or three years. They’ll pick up the phone and begin to dial, and lose courage. One day, they make the call. “You have to get them at the moment that they call, at that very moment when they have said ‘OK, I’m going to get the help,’ ” Harris said.

She is always ready for that call, on the clock 24/7, she said. “Just ask my husband!” she said with a chuckle. “When people ask what my hours are, I just say, ‘When you need me.’ ”

“I don’t have my own little world where they can come and succeed and then they have to go out into the real world and it doesn’t work,” she said. Harris coordinates with family members, teachers, and doctors to make sure that students are getting the help they need to succeed outside of the clinic and develop the skills to thrive on their own.

“If I give you a fish you’ve got dinner, but if I teach you how to fish you’ve got meals for a lifetime,” Harris quoted. “I’m constantly teaching them how to fish so that they can be self-empowered.”

Harris has worked with more than 5,000 students from the Chippewa Valley and northwestern Wisconsin during her 50 years teaching at and owning the reading clinic. But she has also served on the Eau Claire Area School Board (1971-1986), taught at UW-Stout and UW-Eau Claire, spoken for professional companies about ADD, and contributed to her community in countless other ways. “What I try to do is make changes,” she said. “My way of (making a difference) instead of one by one with each student is to teach and serve in the community.”

She expects a lot from herself, she said. But even when Harris is challenged, she loves what she does. “I am able to think of it not as a job,” she said. “It’s doing my passion, and being able to get paid for it.”

“When I wake up, and go, ‘Aww gee, I’ve got to go to work today ... ’ that’s when I’ll have to retire,” Harris said. “And it hasn’t happened yet. Hopefully never.”

This year, Harris is looking forward to a reunion party in the fall to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the clinic’s opening. She is reaching out to invite past students, their parents, and other learning therapists she has worked with over time. However with so many people to contact, and a good portion having worked with her before the advent of cell phones or social media, she will have to do some sleuthing to issue invitations to everyone. Former students are welcome to reach out to the clinic for more information about the event.

She regards many of the people she has worked with as family. Harris attends graduations, meets up with people, and saves mementos from her time with every student. Bober’s file is more than an inch thick, and contains a copy of her dean’s honor roll certificate from UW-Superior, and photos of her high school graduation. When former students are gathering materials for photo albums or scrapbooks, they often reach out to Harris for photos. And the sentiment is mutual; Bodenschatz still refers to Harris as a “second mother.” Shelly, Robert’s mother, prizes this quality in Ruth. “To me her biggest gift is that she is able to connect with those kids,” she said.